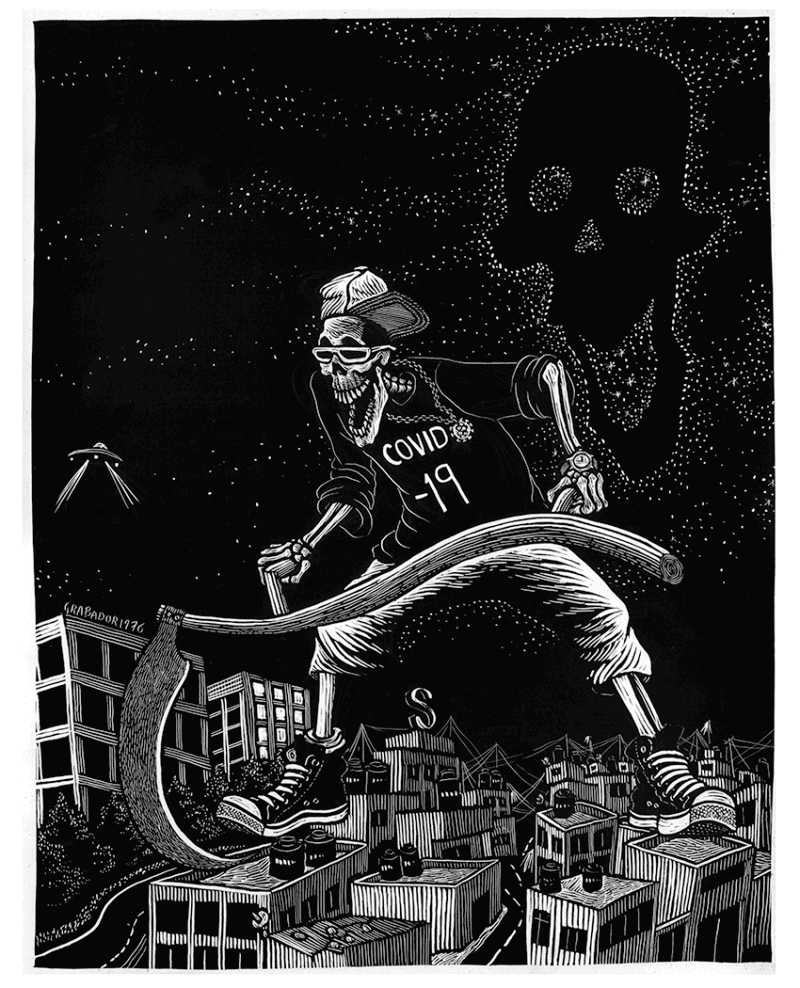

A catrina holding a scythe hovers over a Mexican municipality. In the background, the stars in the night sky form the shape of a skull. The skeletal figure in the foreground wears 21st-century attire — a backward ballcap, sunglasses and sneakers. And on the catrina’s jersey is a decidedly contemporary phrase: Covid-19.

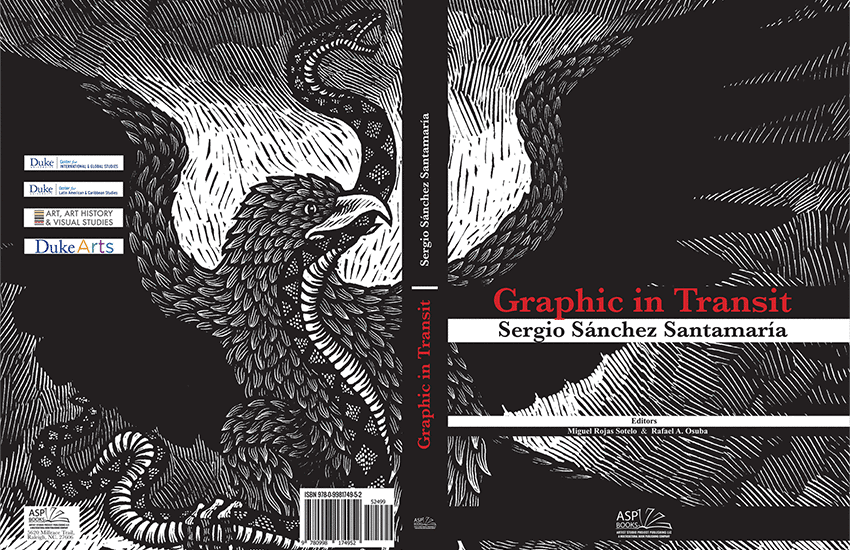

This black-and-white image is among the many selections from acclaimed Mexican printmaker Sergio Sánchez Santamaría in the new book, Graphic in Transit, launched in March over Zoom.

“The opportunity to look at the work of an artist as prolific as Sergio is a very good problem,” said Miguel Rojas Sotelo, one of the book’s editors, along with Rafael A. Osuba.

Rojas Sotelo, an art scholar, is the program coordinator for the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. “In a sense, we tried to do some curatorial renderings of some of the themes that are very present in the work of Sergio,” he said.

The idea for the book was sparked by one of the major collectors of the artist’s work — Duke emeritus professor Robert Healy — who is also based in North Carolina and has known the artist since the late 1990s. About six years ago, Rojas Sotelo and Healy were discussing the Taller de Grafica Popular or TGP, a Mexican art collective first founded in the 1930s concerned with using art to advance revolutionary social causes. The subject of Sánchez Santamaría came up.

“Bob said, ‘I do have this impressive art from someone who started very young and [who] is not that well-known,’” Rojas Sotelo recalled. “We started working on a way to bring Sergio to the U.S.”

Sánchez Santamaría has since come to Duke several times, interacting with young American art students and having his work exhibited. Now it is the subject of a book.

He sees connections between his art and the TGP — “probably the second-most well-known and important art movement from Mexico after the muralists,” according to Rojas Sotelo. That’s true not only due to the themes of social justice that resonate in Sánchez Santamaría’s work but also through his possession of the printing press of one of the TGP’s co-founders and best-known artists, Leopoldo Méndez.

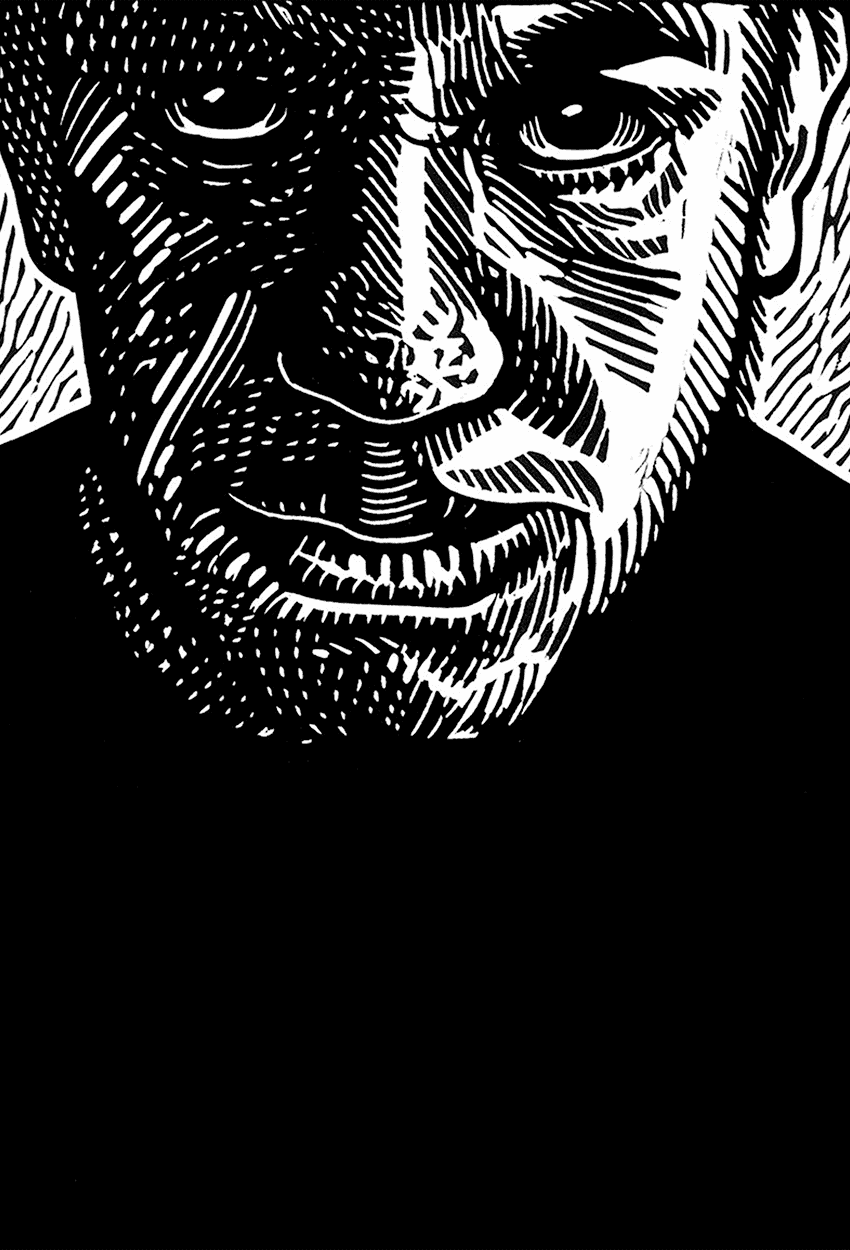

A native of Tlayacapan in Morelos, Sánchez Santamaría still makes his home there, where roosters could be heard crowing in the background as he was interviewed over video conferencing software along with Rojas Sotelo from a separate location. Sánchez Santamaría describes himself as growing up in an artistic family with indigenous roots, as well as possible Black slave ancestry.

“My original intention was to become a sculptor, working with stone like Michelangelo,” he said. Yet he became curious upon seeing lithographs at a museum, including ones by artist José Jorge Chávez Morales.

“This style left an impact,” he recalled. Eventually, he got into printmaking after being introduced to the work of masters like Méndez.

Like the TGP artists in 20th-century Mexico, Sánchez Santamaría’s art reflects a concern with contemporary issues of social justice.

“Discovering his story, we were thinking it was … very powerful …” Rojas Sotelo said. “Not only because he’s an incredible, very talented graphic artist — he is an artist with a capital ‘A’ in all respects — [but] because of [his] lines of connection to history with revolutionary art in Mexico.”

Rojas Sotelo cites a print that Sánchez Santamaría made while a visiting artist at Duke University. It depicts a real-life incident in which ICE agents arrested a young asylum-seeker from Honduras who was eventually deported.

“There’s a very direct link with the history of the TGP” and Sánchez Santamaría’s work, Rojas Sotelo said.

Another image, entitled Viva Mexico, is a complex depiction of the Mexico-U.S. border through such images as that of the Virgin of Guadalupe, a mulatto woman, the Aztec serpent god Quetzalcoatl and the skyscrapers of the United States.

On one side is a Mexico troubled by unemployment and starvation; on the other side is the American Dream, represented by skyscrapers. The two countries are separated by the dangers of the desert and the Río Grande. “It’s very interesting, the kind of work he does,” Rojas Sotelo said. “There’s a documentary journalistic aspect.”

Another way Sánchez Santamaría addresses Mexico-U.S. border issues is by a depiction of an indigenous nahual as a modern-day coyote leading migrants north.

“He does research on indigenous traditions that still play a role in many of the little towns of deep Mexico,” Rojas Sotelo said. “He loves the idea of el coyote as an owl nahua. The magical, mystical garb at the same time represents an animal moving across a territory. It doesn’t have a border. A nahual or spirit man moves across another [territory]. It’s what a coyote does. It’s very powerful, these visual representations of Mexican traditions.”

More recently, Sánchez Santamaría addressed the Covid-19 pandemic with an updated version of the Mexican Revolution-era catrinas of Jorge Guadalupe Posada. This was done on scratchboard in a style that resembles a print.

It depicts “my new catrina, a character from this era,” the artist said, yet he sees many parallels with history, including with Posada’s catrinas. He also finds a connection with the medieval woodcuts of the victims of death by Hans Holbein the Younger.

Sánchez Santamaría cites one such Holbein woodcut of a monk:

“In this example, the dead wears a monk’s habit. The monks are the most impressive people; they speak the word of God.” Yet this cannot stop them from dying, he notes.

Unlike in Holbein’s work, Sánchez Santamaría’s catrinas are “not monks, they are more like reggaeton [singers],” dressed in Bermuda shorts and tennis shoes.

In addition to his political themes, some of his other prints show images of nature in Mexico, as well as depictions of the Mexican gallo, or rooster, and even of traditional maize.

“I am particularly interested in his work on representing nature,” Rojas Sotelo said. “His work is full of references to Mexico’s geography, to plants, to trees, to locations.”

Sánchez Santamaría also does works related to his interest in tattoos, as well as to his love of music — he wore a Pink Floyd hoodie during the interview.

“His work is multifaceted,” Rojas Sotelo said.

Indeed, he noted, “[Sánchez Santamaría’s] work has a lot to do with reacting to the times. It’s reflective of kind of what we have with issues of identity, what constitutes being a subject in today’s Mexico, identity constraints on Mexicans, a presence of this hybridizing mix of what Mexican culture is. He reflects on that.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.