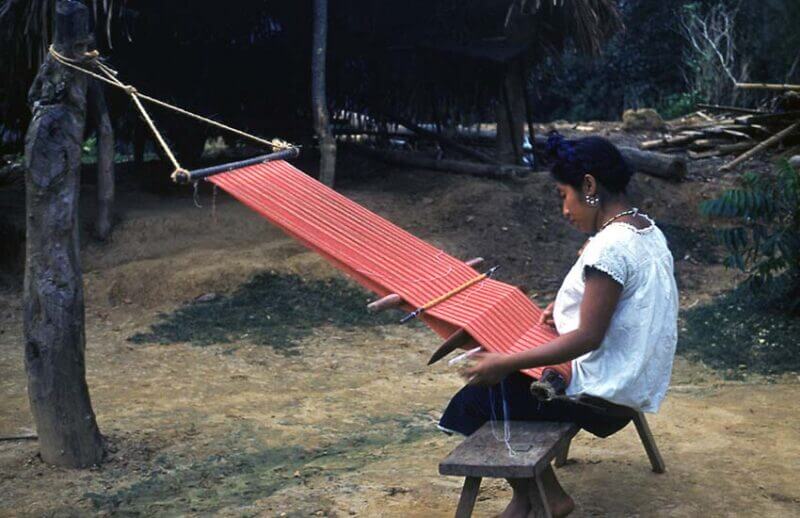

When anthropologist Frances Berdan did fieldwork with indigenous weavers in Puebla’s Sierra Norte, she made a surprising discovery: although the women weavers she observed were using store-bought thread or wool alongside the once-preferred cotton, they still made cloth using traditional backstrap looms as Aztec girls and women had done centuries before.

This firsthand experience is one of many ways she finds continuity and complexity in the narrative of the famed empire in her new book, The Aztecs.

“I have researched the Aztecs and their civilization for half a century,” Berdan said in an email interview. “That said, I’m still learning new things about them.”

Part of the Lost Civilizations series published by Reaktion Books, The Aztecs suggests new ways of seeing its subject: instead of focusing on leaders like the ill-fated Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, she expands her lens to include the people they governed.

“Historical accounts generally focus on the powerful – kings and nobles,” Berdan, a professor emerita of anthropology at California State University in San Bernardino said. “Fortunately, some of the ethnohistoric records that we have also address a wide range of people — men and women, adults and children, priests and teachers, farmers and artisans, merchants and porters … doctors. And slaves. And more.”

The book uses artifacts as a jumping-off point for a wider narrative about the empire and its people. One such artifact is a feathered shield that wound up in Habsburg Austria. Its feathers came from multiple bird species, from quetzals to spoonbills. It depicts an image of a canine figure that might be a coyote, Berdan says. Only four such shields survived the conquest.

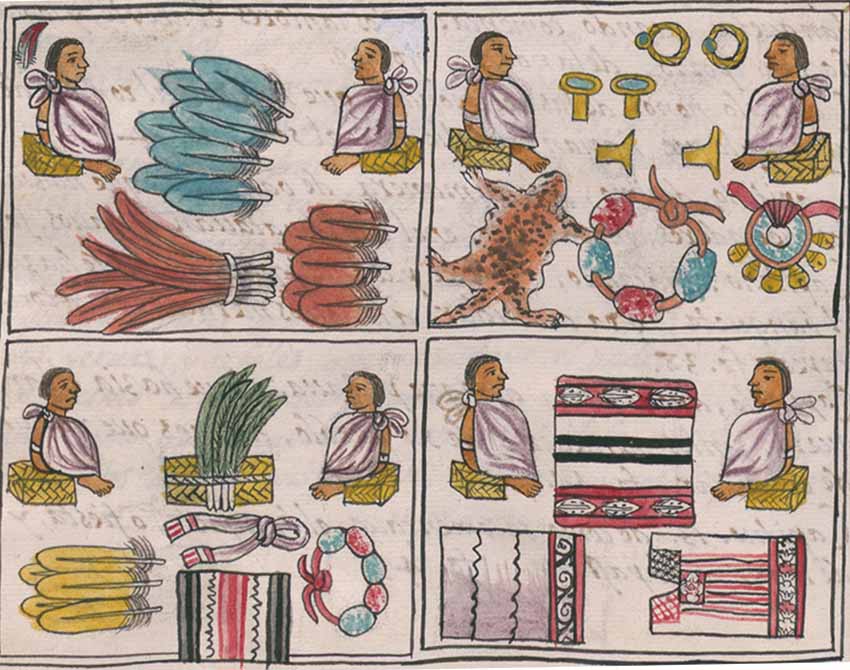

In addition to feathered shields, Aztec artisans made objects ranging from reed mats to obsidian knives. Some items were bartered on the empire’s frontiers in locations that Berdan describes as international trading centers.

This is the author’s second consecutive book that seeks to broaden discussion of the civilization, following Everyday Life in the Aztec World, also released this year. She also has written a book on Aztec archaeology and ethnohistory and co-edited a volume about the Codex Mendoza, a manuscript written around 20 years after the conquest by indigenous authors and depicting Mexica history, society and daily life before colonization.

Her latest book “not only presents the general ‘big picture’ of the Aztecs as an empire and civilization but also spends a great deal of time discussing the activities, behaviors and beliefs of the people themselves, whether they be nobles or commoners,” she said. “The book focuses on people as they engage in farming, marketing, marrying, raising children, healing wounds, participating in rituals, fighting on the battlefield and myriad other activities.”

These activities included textile production. The book states that it may have been the most “ubiquitous craft in Mesoamerica,” and that all women in the empire learned to spin and weave, “from Tenochtitlán to rural villages.”

In areas added to the empire by conquest, women had to make textiles for about 300,000 items of clothing delivered annually to their Aztec overlords, the most common type of tribute paid, according to Berdan. In the arduous process, a woman or girl spun cotton or maguey fibers on a spindle, then wove them into cloth on a loom strapped to her back.

Berdan said it was “eye-opening” to see weavers use these ancient techniques today.

“The 16th-century documents provide us with images of weavers and some descriptions of their activities,” she said, “but here were women expertly weaving cloth very much as it has been done for hundreds and hundreds of years … and I could talk with them!”

The indigenous women of the Sierra Norte told Berdan that they had mastered the process by age 14, which historical texts say was also the case in the ancient empire.

Berdan describes the Aztecs as “meticulous artisans” and cites this as among a number of clarifications she wishes to make about the ancient civilization in her new book.

After the establishment of Tenochtitlán in 1325, the city-state expanded over the decades until it became an empire that reigned for nearly a century. It grew through negotiation as well as conquest, Berdan notes, and the people within its borders would have called themselves Mexica, not Aztecs.

Beyond these points, the book describes the civilization’s scientific achievements as impressive, from astronomers who calculated a 365-day solar calendar to farmers who used innovative agricultural techniques such as terraces and chinampas — small artificial “islands” of soil built on a freshwater lake for agricultural purposes.

Furthermore, she finds the Aztec religion more multidimensional than the usual narrative of human sacrifice we hear today. “Aztec religion was rich and complex,” she said. “The Aztecs worshipped many gods and goddesses (each with their own temples and cadres of priests), recited colorful myths and performed frequent ceremonies with processions, offerings, dances, music and song. Some — but not all — of these ceremonies included human sacrifices.”

The Aztecs sacrificed both humans and animals to the sun god Huitzilopochtli — for light and warmth for the all-important maize — and to the rain and water deities, Tláloc and Chalchiuhtlicue, for sufficient rainfall.

“Human sacrifices were always conducted in ritual contexts,” Berdan said, “although some of the large numbers of sacrifices we hear about relate to an added political dimension where a Mexica king wished to intimidate both his enemies and his allies.”

Even when it comes to the conquest, Berdan finds cause to challenge an existing narrative, in a chapter entitled “The End of the Fifth Age: The Setting Sun.”

Nahua perspectives of the conquest and its direct aftermath, she said, are “quite different than the usual narrative of the conquest.”

For instance, she explained, “the Spaniards’ native allies, such as the Tlaxcalans, did not view themselves as part of a Spanish enterprise but rather looked at the Spaniards as helping them to fight and conquer their longstanding Mexica enemies.”

Despite the fall of Tenochtitlán and the devastating epidemics that followed over the ensuing decades, Berdan questions to what extent the Aztecs were actually conquered, noting that about two million people speak Náhuatl in Mexico today.

In the Huasteca — a region located partially along the Gulf of Mexico and touching parts of seven states, the language is growing in vocabulary, adding new words for recent innovations. Email, for instance, is tepozmecaixtlatiltlahcuilloli, or “apparatus where writing is delivered to your face.”

Another fusion of past and present can be seen during Day of the Dead: ofrendas include not only the modern beverages of Coke and Pepsi but also the Aztec staples of atole and tamales.

“The Aztecs viewed life and death as a constant cyclical process,” Berdan said. “Day of Dead ceremonies are very important in Mexico today and reinforce ties between the living and the dead. It is another example of the fusion of indigenous and Spanish traditions.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.