Situated in Campeche 35 kilometers from the border with Guatemala, in the second-largest tropical forest in the Americas, Calakmul is one of the most significant Maya ruins in present-day Mexico.

UNESCO declared Calakmul — located in the Calakmul biosphere reserve — a World Heritage Site in 2002. The area that includes the protected biosphere was declared a Mixed Natural and Cultural Property in 2014. The site is located 60 kilometers from Highway 186, through the jungles and much wildlife — notably ocellated turkeys. On our trip from Xpujil, we saw only a few tourists.

Discovered in 1931 by biologist Cyrus Lundell, calakmul is Mayan for “Two Adjacent Mounds,” referring to its two largest structures. Calakmul is thought to have been occupied from 550 B.C., peaked in development during A.D. 250–900 and abandoned around A.D. 1000.

During A.D. 636–695, the city developed an extensive sociopolitical network before being defeated by the rival Maya city, Tikal. The kingdom continued afterward, and subsequent rulers had focused on establishing relationships with other cities like Río Bec in the north.

During its peak, the kingdom controlled an area over 13,000 square kilometers with an estimated population of over 1.5 million. Around 18 rulers have been identified by archaeologists so far.

Researchers have determined that Calakmul was a pilgrimage site during A.D. 1000–1500 due to the offerings discovered inside buildings.

The archaeological zone extends over 70 square kilometers with more than 6,000 structures, but only a portion is open to the public. The site has around 120 stelae, carved or inscribed stone slabs or pillars used for commemorative purposes, the greatest of any Maya site.

There are several reservoirs in the area built by the ancient Mayas to collect rainwater; the largest measures around 242 by 212 meters. There are also useful notices with historic information at the site from the Ministry of Culture and the National Institute of Anthropology and History. You can climb most of the buildings.

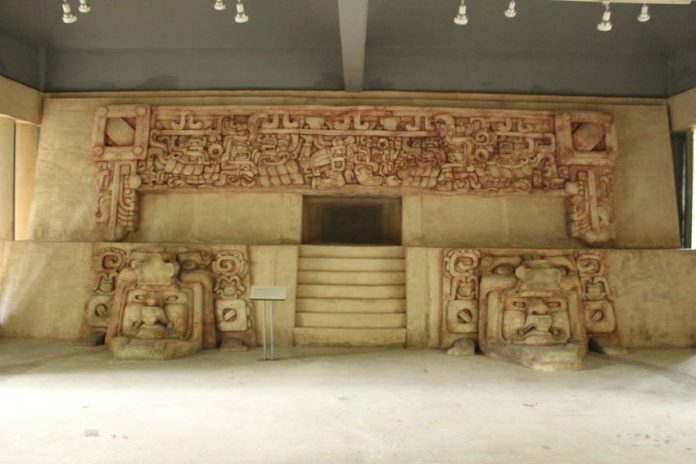

The display area at the entrance has replicas of art and sculpture, including a model of the large frieze from the main pyramid.

We entered the Great Plaza from the north, by a stela from around A.D. 721, and a small pyramid with a possible astronomical purpose. The stela’s visible text is said to depict an ancient name of Calakmul, Uxte ‘Tuun, meaning “Three Stones,” as well as a reference to the most powerful rulers.

The plaza, measuring 250 by 150 meters with six structures around it, is the center of Calakmul, where ceremonies and political events took place. Archaeologists have identified this section as having the oldest and longest-running occupation. It was continuously occupied until A.D. 1000. Most buildings here have held tombs of rulers and elites.

South of the plaza is Calakmul’s most significant pyramid, the spectacular Structure II, measuring around 55 meters in height, on a 140-meter square base. There are four buildings on top of the main structure. To the north are the palace buildings, and to the rear is a temple. It is the highest point of the pyramid and not visible from the ground.

Some notable findings from the Structure II pyramid are nine tombs, including that of King Jaguar Claw, who ruled during A.D. 686–695; a frieze depicting different characters and large stucco masks. The pyramid is thought to represent the mythical sacred mountain Witz, whose interior was believed to have access to the underworld.

There are several stelae on the base of the pyramid. One dates back to A.D. 431, the time of the earliest known ruler. The most prominent stela on the pyramid, from A.D. 692, is thought to represent Jaguar Claw’s wife or mother performing a ritual. There are remains of large masks on either side of the main stairways.

Over time, this complex had been used for a variety of purposes: a residence for the rulers, elites, and their workers; a burial site and a location for political, ceremonial, and religious activities. The views from the top of the Structure II pyramid across the biosphere are breathtaking, and you can visualize the great kingdom from here.

North of the Great Plaza is a temple pyramid measuring around 24 meters in height, facing the Structure II pyramid. There are five stelae in front and room structures on top. An eighth-century tomb with jade masks and other ornaments was discovered here. Another notable discovery was the Mask of Calakmul, now in the Museum of Mayan Architecture in Campeche city.

East and west of the plaza are a set of buildings called the E Group, considered to be astronomical in purpose since solstice and equinox observations can be done there. The stelae on top of one of the buildings are considered possible observation points. Another building, referred to as Structure IV, has three main buildings — the central Structure IV-B and two temples on each side. A stela depicting the birth of Jaguar Claw, now in San Miguel’s Museum in Campeche city, as well as the tomb of a ruler were discovered here. While the tomb was looted, some of its funeral offerings have been recovered.

Another monument in the plaza worth seeing is a stela from A.D. 721 created by King Yuknoom Tok’ K’awiil, recording a ceremony conducted in A.D. 593 by an ancestral ruler, The Coiled Snake.

The 12-room elite residence building known as Lundell Palace, to the east of the plaza, is also worth seeing. A tomb of a possible ruler was found here.

West of the plaza is the Great Arcópolis, a complex which features residential buildings, temples and a ball court. The tallest building here is a pyramid with a two-layered building on top. The stela on the stairway is said to depict a woman with a ceremonial staff.

In another building in this section, there are the tombs of three elites.

Unfortunately, the Acrópolis has been cordoned off to visitors with the ongoing pandemic, but if the state of Campeche stays green on the coronavirus stoplight map, that might soon change.

The Chii’k Naab’ Acrópolis to the north of the plaza, with its mural paintings discovered depicting scenes from daily life, is also significant. Chii’k Naab’ means “House of the Water Lily,” and the acrópolis here is a quadrangular area with 68 structures.

There are other structures to explore, including the Small Acrópolis to the east of the plaza and residential buildings to its north, but a must-see, however, is the Calakmul Museum of Nature and Archaeology, around the 20-kilometer marker on the road to the site. It has information about the kingdom of Calakmul and the region since the time when a meteor hit Earth on the Yucatán Peninsula over 65 million years ago.

Thilini Wijesinhe, a financial professional turned writer and entrepreneur, moved to Mexico in 2019 from Australia. She writes from Mérida, Yucatán. Her website can be found at https://momentsing.com/