The human race has become complacent. Once upon a time pestilence was something to worry about, but a few decades of relatively mild epidemics — and the discovery of medical fixes to keep them at bay — led most of us citizens of the 21st century to believe that pestilence and plague were things of the past.

This new virus, however, has shaken us. It is suggesting that maybe we were taking too much for granted, that we didn’t know how good we had it. It even dares criticize us for dedicating our few precious years of life to fun, football and Facebook.

Pestilence has visited Mexico before and those few epidemics that were recorded were far worse than this coronavirus.

The native people’s word for plague was cocoliztli and they used it to describe epidemics that swept through Mexico in 1520, 1545 and 1576.

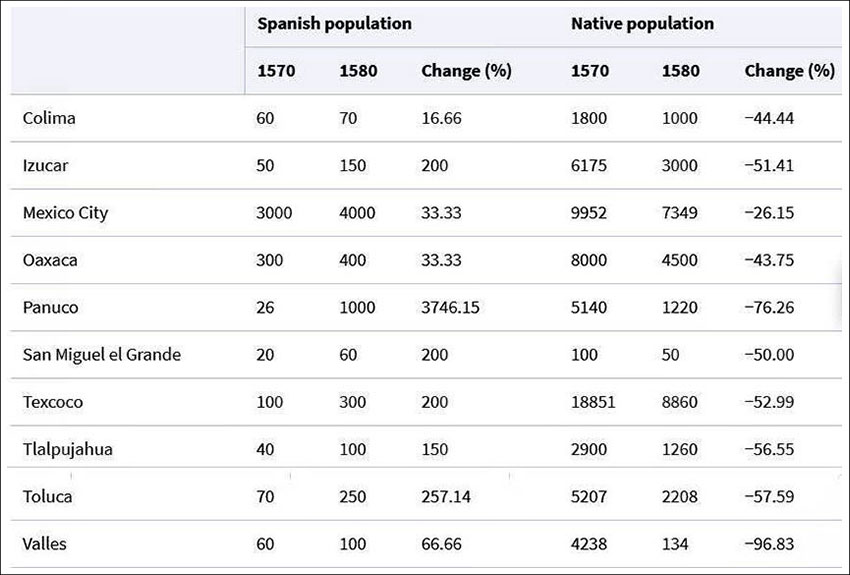

The first of these was caused by smallpox, brought here by the Spaniards. It devastated the native population but hardly bothered the Spaniards.

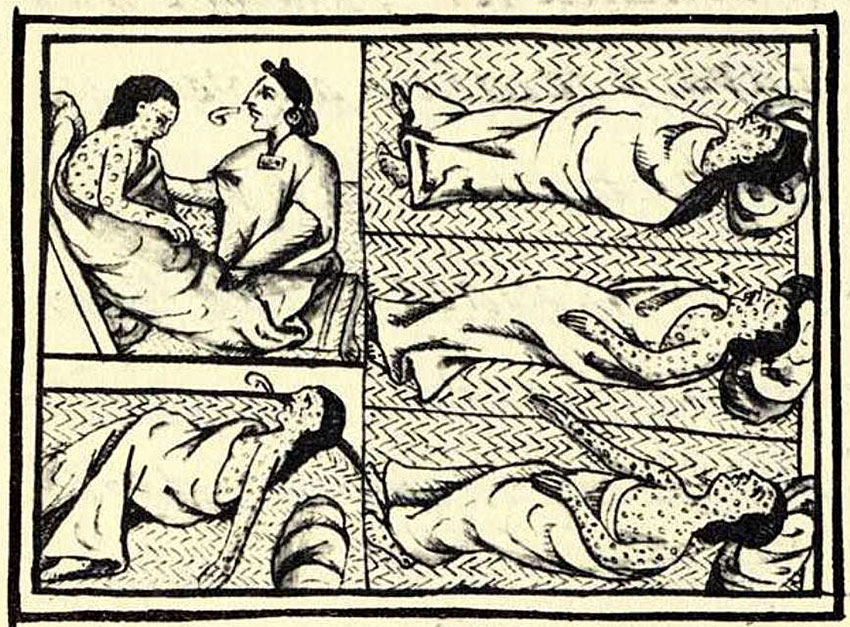

In the Florentine Codex, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún says that the disease “brought great desolation: a great many died of it. They could no longer walk about, but lay in their dwellings and sleeping places, no longer able to move or stir. They were unable to change position, to stretch out on their sides or face down, or raise their heads.

“And when they made a motion, they called out loudly. The pustules that covered people caused great desolation; very many people died of them, and many just starved to death; starvation reigned, and no one took care of others any longer.”

The second epidemic hit Mexico only 25 years later. This one was far worse than the previous. The Spaniards had no idea what it was, so they gave it the name that the local people were using: cocoliztli. Spaniards who described it said the disease began with a high fever and headaches followed by bleeding from the eyes, mouth and nose, in fact from every bodily orifice. The victims’ tongues were dry and black and they experienced enormous thirst as well as delirium, dysentery, seizures and vomiting.

Whoever caught cocoliztli died within three or four days. It has been described as “a combination of hemorrhagic flu, yellow fever, jaundice, viral infection, malaria, typhus and typhoid.” Such a description, perhaps, is just a way of saying it was terrible but no one knew what it was — up until 2018, that is, when a team led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany analyzed DNA extracted from the teeth of 29 skeletons buried in a cocoliztli cemetery.

What they found were traces of Salmonella enterica. Apparently salmonellosis, when unleashed upon those who have no resistance to it, is more devastating than we could ever imagine.

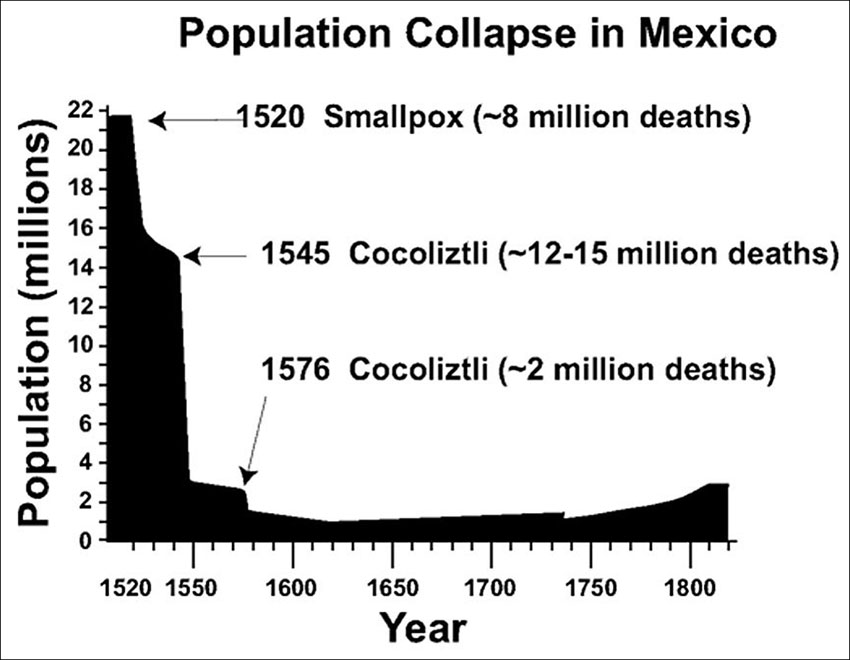

As you can see in the graph, smallpox struck in 1520 and killed an estimated 5-8 million people. Then, a few years later, two outbreaks of cocoliztli exterminated half of the remaining population.

This graph, taken from an article by Acuna-Soto et al in Emerging Infectious Diseases, says a lot, but it doesn’t say everything. Living in 2020 we know what has hit us and how it is transmitted. We have strategies for combating it and we can see ourselves defeating it in the near future.

The indigenous people of 16th-century Mexico could see none of this. How did they cope?

It’s no surprise that death inspired all sorts of rituals, customs and even philosophies here in Mexico.

We joke that nothing in life is sure except death and taxes, but even taxes are forgotten when overtaken by death. Says Fray Bernardino, “The worst attack of cocoliztli took place between 1567 and 1578 when it spread throughout the country, leaving more than 2 million dead. They say the towns were desolate and fields, mines and industries were abandoned. The viceroy was obliged to cancel and write off taxes and duties which were impossible to collect with things in such a state.”

Over many many centuries of cocoliztlis, people in what we now call Mexico developed a perspective based on the inescapable reality that death stalks every one of us and it’s impossible to know when it will finally do us in. The most obvious manifestations of this perspective are the traditions associated with El Día de los Muertos which are so unique that UNESCO considers them part of Mexico’s contribution to the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

A less flamboyant reaction to the reality that death is always around the corner is a code of behavior — supposedly developed by the Toltecs — called el sendero del guerrero or the warrior’s path, which urges us to carry out everything we do with impeccability, as if thumbing our nose at death.

Our present-day cocoliztli is forcing us to look at age-old questions: what will we take away with us when we go?

Life, said my teacher Caleb Gattegno, “is turning time into experience.” We can dedicate the limited amount of time given to us to fun, football and Facebook but, if Gattegno was right, the only thing we will be able to take with us when we die is awareness.

What awarenesses is our cocoliztli of 2020 bringing us?

COVID-19 is turning many of us into hermits. So why not do what hermits do and take a little time out for meditation?

Has COVID-19 made you aware of something you were not previously conscious of? Has your outlook changed? Have you changed?

If so, I hope you’ll share your thoughts and leave a comment below.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.