The pools of Cuatro Ciénegas (four marshes) in Coahuila’s Chihuahua Desert conceal a very old secret: the origins of life on Earth.

They are inhabited by colonies of bacteria-formed stromatolites, organisms considered the inventors of photosynthesis. They are formed by bacteria that use water, carbon dioxide and sunlight to create food, expelling oxygen as a by-product. The real significance of stromatolites is that they are the earliest fossil evidence of how life began.

Cuatro Ciénegas is a unique biosphere — literally an oasis in the desert at an altitude of 740 meters. Located northwest of Monclova, the area owes its name to abundant springs that form extensive marshes and pools in the middle of the desert.

The city is formally known as Cuatro Ciénegas de Carranza, in honor of its most famous son, Venustiano Carranza, president of Mexico from 1915 to 1920, who was born there in 1859.

The intriguing landscape is the result of a sea that, millions of years ago, emerged at the same time as the Sierra Madre Oriental. Its folded and fractured marine rocks formed most of its mountain ranges and hills.

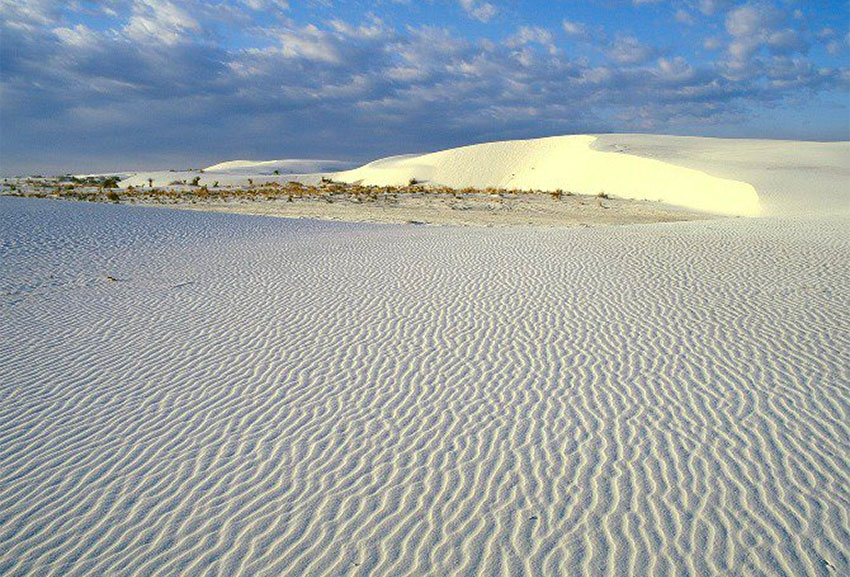

Two things immediately strike you about Cuatro Ciénegas: tomb-like silence and the surreal shroud that encases it. Some say they feel currents of occult energy flowing like fog, ebbing in town, peaking at the bright-white dunes. It flows steadily through the transparent azure wells.

According to some, the energy is peaceful except by the old mines where it is sad. Listen to Cuatro Ciénegas yourself and, they say, you may hear your soul coming out to mingle with the soul of creation.

Some writers claim you need four-wheel drive to visit all sites of interest. Balderdash, I say. Except for one inaccessible well, the attractions are on paved roads.

Pozo Azul and Las Dunas de Yeso are the two most photographed, iconic spots. Next are Poza la Becerra and Río Mezquites, where you can swim, legally. Kayaks are available. Sunscreen or lotions are prohibited. Other attractions include the Bodegas Ferriño Winery and a spectacular canyon in the nearby mountains.

The gypsum dunes rise to 12 meters and resemble those of White Sands, New Mexico, where I grew up. Gypsum is used in cement, drywall and agriculture. From 1979 to 1996 it was mined — scooped up — on an industrial scale at Cuatro Ciénegas. Though officially banned in 1996, residents say it still goes on.

Scientists believe there are clues to life on ancient Earth in the landscape — microbes, bacteria, fossils and fish. There are live stromatolites in the pools and fossils on the edges. These cauliflower-like sponges are relics of the earliest microbes on earth.

The area has been designated a biological reserve. But farmers still extract water and miners and bucket loaders still shovel gypsum. It’s a Pueblo Mágico, or Magical Town and, since 2006, a United Nations-recognized biosphere reserve. In 2007 president Felipe Calderón took a few baby steps to limit water extraction on the Chihuahua Desert.

Two things menace the springs — huge alfalfa farms that suck water from the aquifer and Arundo Donax, an invasive giant reed that threatens native species and the water supply. Much of the water is covered by this reed.

Compared to my first trip three decades ago, my guess is that 30% of the pools are gone or covered.

Meanwhile a debate rages about which herbicide will be safe enough to kill the invaders, but not the native flora and fauna.

There are reputed to be more than 500 springs feeding the pools. Water temperatures vary by season and pool. Averages are 20 C in Poza Azul (winter) to a balmy 32 C in Poza Escobedo (summer). Some pools are transparent, like Yucatecan cenotes. Others are turquoise, aquamarine, cerulean or teal, depending on sky conditions.

Swimming and camping are allowed only at Poza Becerra. But we saw swimmers elsewhere who missed the memo.

Everybody in Cuatro is, knows or is related to a guide. If you don’t need a college-level lecture on the ecosystem, they do just fine. On many paths there are signs describing the flora and fauna as well as in a remarkably good on-site museum.

As a local guide, the folks at the Plaza Hotel recommended Raúl, a man in his 30s who spoke English and had a friendly, intelligent demeanor. He took us where we needed to go; told us what we needed to know.

You don’t need a guide, but I like to help the local economy. A local will always know more than I do. Raúl went one step farther. The photographer wanted to do some astrophotography at the dunes.

The access road was blocked by a locked iron gate at night but Raúl had a key. So, late that night, we went to the dunes and he shot to his heart’s content.

Downtown is always a trip. Owners of the few restaurants came out and greeted us like family. People stopped what they were doing, smiled and said “Hello.”

In all my years of traveling Mexico, I can’t remember a friendlier town. We also visited President Carranza’s museum.

You can camp at Poza la Becerra or there are four good hotels. I stay at The Plaza (1,255 pesos). There’s Hacienda del Caballo (1,200 pesos), Hostel Doña Carlota (1,050), San Pablo (840) and the luxury Hacienda (1,800). There are several friendly, inexpensive restaurants on the town square and at most hotels.

Cuatro Ciénegas is in northeastern Coahuila, 73 kilometers west of Monclova. From Piedras Negras it’s 306 kilometers.

In summer, the devil has a condo there. My last trip was in the fall, which has perfect, dry temperatures in the day and a little cooler at night. October-November highs average 24-28 C with lows of 9-15 C.

Visiting the stromatolites at Cuatro Ciénegas is like going back four billion years to view the beginning of life.

“Mexico Mike” Nelson was a prolific author of books and articles about Mexico travel and culture in the 1980s and 1990s. Rumors of his demise are only partially true. He says he’s just been resting on his laurels. More of his work can be found at https://www.mexicomike.com.