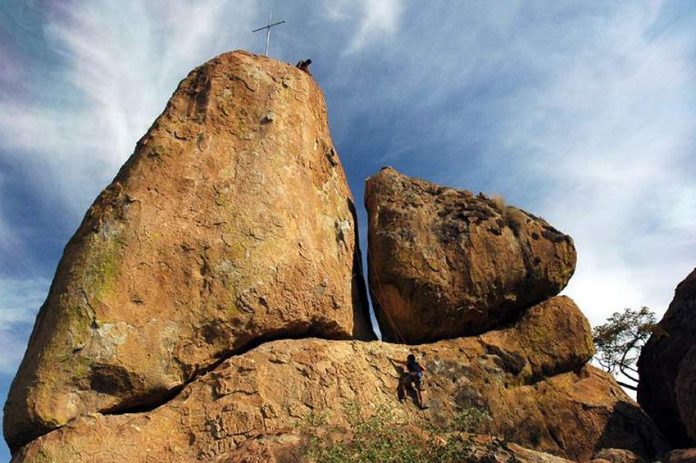

The hills above the little town of Río Blanco, Jalisco, are covered with a curious forest consisting not of trees but of hundreds of huge, smooth, rocky spires.

One of these monoliths happens to have the shape of a giant tooth and has given a name — El Diente — to this extraordinary place of solitude and natural wonders, located only minutes from Mexico’s second largest city.

“When I first saw El Diente, I was quite surprised,” Canadian geologist Chris Lloyd told me. “The geological maps of this area show nothing unusual, but when I got here I found they were wrong. These monoliths are amazing.

“They are composed of a rather pure feldspar porphyry which formed deep under the earth perhaps up to 30 million years ago. That’s how long it’s taken the surrounding rock to erode away, leaving these extremely old monoliths standing tall. Geologically speaking, this is a very special place.”

The rock climbers of Guadalajara discovered the monoliths of El Diente many years ago and for a long time they considered them their big secret. “The rock is very hard,” says Luis Medina of Jalisco Vertical, “and the monoliths come in so many different shapes that climbers can practice every technique and maneuver imaginable, sometimes only two meters above the ground.”

Another thing that attracted the climbers is the silence. Wandering among these curiously shaped rocks, all you can hear is the chirping of birds, the chattering of squirrels and perhaps an occasional expletive from a climber who has missed his or her handhold and is — hopefully — about to be caught by the belay rope.

But the silence of El Diente is all the more extraordinary because this geological wonder is located only six kilometers from Guadalajara’s noisy, ever-busy Periférico or Ring Road.

The Diente monoliths are part of El Bosque de Nixticuil, which was once an impressive forest but over the years was eroded away by land development schemes of all sorts. Since 2008, what’s left of this woods has been officially “protected” but seemingly still under threat, as was evidenced in 2012 when rumors circulated that El Diente had been bought up by developers who were going to fence it off, shutting out the boulder climbers from their favorite weekend hangout.

“We were going to organize a festival called Salva El Diente, Save the Tooth,” says Luis Medina, “but when the developers heard about it they assured us they would never cut us off from our beloved rocks and we all joined together in a Vive El Diente International Festival of solidarity.”

Well over a thousand rock climbers from all over the world participated, including California’s Lisa Rands, said to be the best boulder climber anywhere, and Mexico’s national bouldering champion, Fernanda Rodríguez of Guadalajara, who called the event “padrísimo” [totally cool], perhaps the best qualification possible from a modern young Mexican.

“The festival was a great success,” commented Luis Medina, “because it brought the existence of El Diente to the attention of the authorities, of politicians and of many organizations. In addition, it turned out to be one of the biggest outdoor events in Mexico’s history.”

Several years after the festival, archaeologist Francisco Sánchez visited El Diente as part of a survey conducted by CIDYT, the Center for Dialog and Multidisciplinary Research, to catalogue the resources of the Nixticuil woods.

“I know it sounds strange,” Sánchez told me, “but in the nearby pueblito of Río Blanco I met a woman who told me she had had a dream that long ago people had lived on top of a certain hill just 400 meters southeast of El Diente rock. So I went to see the hill she indicated and even before I reached its base I began to find artifacts: the foundations of stone walls. The further I went up, the more it was clear that this hill had been terraced, but not for farming, and then, at the top I found the base of a pyramid.”

“The ground here,” Sánchez told me, “is covered with tepalcates [shards] and fragments of worked obsidian. The ceramic pieces pinpoint the builders of these structures exactly. This civilization flourished during the Epiclassic period, from 650 to 900 A.D. They are the same people who built the Ixtépete pyramid just outside Guadalajara and are referred to by archaeologists as the El Grillo Tradition.”

Quite near this hill where the ancient pyramid is located, you’ll find the trailhead for an eight-kilometer loop hike that circumnavigates the monoliths of El Diente. This is one of the most spectacular senderos I’ve seen in western Mexico. “The further we went,” I wrote about this trail after first walking on it, “the bigger and more beautiful the rocks got, with plenty of opportunities for us to scramble atop some of them. After hiking three hours at an easy pace, with three rest stops, we reached altitude 1,633 meters, just a hair over one mile high, where we had a magnificent view of the village of San Esteban far below us and, far, far away in the background, the smog-shrouded tall buildings of Guadalajara.

“We stopped for lunch near a truly colossal pinnacle which rock climbers call El Fistol (The Pin) and then we looped around the northwestern edge of the Bosque and returned to the El Diente parking area. This route is scenic every step of the way any time of the year, but it is especially beautiful if you follow it during the rainy season.”

If you are not interested in hiking or in watching boulder climbers do their thing, you can still have a great time at El Diente simply wandering and letting your imagination run wild. I went there with friends one day with no particular plan in mind. “Let’s just look at the rocks,” I suggested and, with every step, one of us would cry out: “This place is incredible; it’s astounding!”

And over and over we would point: “Look at those rocks: two giant turtles; over there, you can see a brontosaurus and here’s a giant finger pointing at the sun.”

Spend a few hours at EL Diente and I swear you will begin to see everything from giant bowling balls to natural bathtubs, and when you’ve seen enough you can sit down in the shade of a towering pinnacle to have a picnic. Just remember to clean up behind you and leave the place as you found it. And whatever you do, be sure not to bring your boombox!

El Diente is only a 16-minute drive from Guadalajara’s northern Ring Road. You can get there easily by asking Google Maps to take you to “El Diente, Zapopan Jalisco.” In case you would like to do the hike I described, check out my map on Wikiloc.

[soliloquy id="64067"]

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.