As the American Civil War began in 1861, Mexico was beginning its own battles, as President Benito Juárez began a fight against the French intervention in Mexico. A little-known fact is that the conflicts coalesced on a single spot that doesn’t exist anymore today: the Mexican port of Bagdad, Tamaulipas, located on the Rio Grande, on the United States-Mexico border.

Now vanished as a result of hurricanes, the memorably named port became a boomtown for a brief moment during the Civil War, making it a prize target for both Mexico’s French-backed imperialistas, who wished to restore a monarchy in Mexico, and the forces of the Mexican Republic.

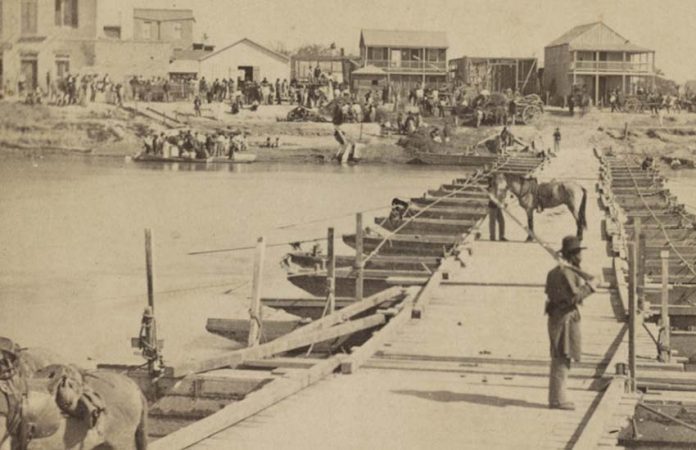

Bagdad achieved prominence because of a loophole in Union policy at the outset of the Civil War. Although President Abraham Lincoln had declared a blockade of southern Confederate ports in order to block the seceded Confederacy’s access to resources, it did not apply to the international waters of the Rio Grande, leaving Bagdad open to trade with the Confederate states. It helped that Juárez’s government had declared neutrality in the Civil War, allowing Confederate states to get their prize cotton crops to international markets.

“Suddenly, there was great interest in the one little square point that would get you around the Union blockade,” said Richard B. McCaslin, the TSHA Professor of Texas History at the University of North Texas.

“It was the only port [where] Lincoln could not block cotton,” said Teresa Van Hoy, a professor of history at St. Mary’s University. “The lifeline of the Confederacy went through the Port of Bagdad.”

Located tantalizingly close to south Texas, Bagdad saw its population increase dramatically. A wide variety of establishments sprang up, including gambling houses and brothels.

Asked about the origins of its name, historians were unsure.

“I don’t know,” Van Hoy said. “It was at the bottom of the river, the mouth of the river. It was not spelled like Baghdad in Iraq, there was no ‘h’.”

“I have no idea,” McCaslin said. “It could be because of the wild nature, the exotic nature, of the place.”

Confederates sent cotton through Texas to Bagdad, where it was loaded onto ships and sent across the world. Meanwhile, supplies arrived in Bagdad for the South, including guns, ammunition, clothing and medicine. Goods were unloaded and brought upriver to Matamoros, then transported across the border to Brownsville, Texas.

“Since Matamoros did not have an outlet to the sea, one was improvised – Bagdad,” said Miguel Ángel González-Quiroga, an affiliated researcher in Mexican history and borderlands studies at the University of Texas at San Antonio. “Many [people] became fabulously rich building their opportunities through Bagdad. It became a really fast boomtown, with maybe 10,000, 15,000, 20,000 people overnight, to take advantage of the Civil War trade.”

The trade there attracted interest not only from the South but also from Mexico and France – and even in the northern U.S., officially at war with the Confederacy.

“Lincoln couldn’t stop New York textile manufacturers from importing cotton,” Van Hoy said. “He dared not upset the flow of cotton supplies … It was a very delicate balancing act. One bale was worth US $10,000.”

“The number one product of the U.S. was cotton from the South,” McCaslin said. “The number one export from Texas was cotton. It was how you made serious money.”

When the French army of Napoleon III invaded Mexico and chased Juárez northward, the Mexican president hung on to Bagdad, where he got crucial financial support.

“[Bagdad] also becomes a lifeline for the Juaristas (partisans of Benito Juárez,” Van Hoy noted. “It’s the only source Juárez has of revenue throughout his resistance [in] Mexico to the French intervention — customs duties. He had no other source of revenue. The French blockaded the major ports — Veracruz and Acapulco.”

Yet, McCaslin said, “I’m not sure [Bagdad] helped Juárez much.”

There was a lot of money for locals, McCaslin said. “How far it got into Mexico, I’m not sure,” he added. “It was so balkanized along the borderlands. To get money to trickle down into central Mexico … I’m not sure. How much Juárez [received], I’m not sure.”

Bagdad found itself in the center of a cross-border controversy, one that made Juárez consider cutting off his Bagdad lifeline.

A Confederate force crossed into Bagdad to capture two Union sympathizers – future Texas governor Edmund Davis and William Montgomery. The pair was brought to Texas, where Montgomery was lynched from a mesquite tree on March 10, 1863.

“This particular atrocity becomes a major international uproar,” Van Hoy said. “Mexico protested the armed invasion, the kidnapping, the lynching. They threatened to close Bagdad to all Confederate exports and imports.”

Although the Confederates mollified Juárez by releasing Edmund Davis, opportunities in Bagdad decreased due to the South’s worsening situation. Union General Ulysses S. Grant’s triumph in the Siege of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, split the Confederacy in two.

After Vicksburg, supplies from Bagdad could only support Confederate areas west of the Mississippi River. From late 1863 to early 1864, Union forces occupied the Rio Grande and shut off Bagdad entirely to the South before withdrawing for another campaign along Louisiana’s Red River.

In a further complication, the French finally captured Bagdad on Aug. 22, 1864. That spring, France had installed Archduke Maximilian of Austria on the throne of the Second Mexican Empire.

“[The French] established good relations with the Confederates across the river,” Van Hoy said. “Now the imperialistas occupied the south side of the river. The Confederates controlled the north [side].”

McCaslin said that “some of the local [Confederate] commanders … had very good working relationships with [imperialista general] Tomás Mejía and Maximilian’s army.”

In the wider sphere, he said, “The French looked to gain Confederate support. They courted [the South] a little bit … Lincoln made a deal with the French: If you don’t interfere with the Confederacy, if there’s no overt recognition, no negotiating, then I won’t interfere in Mexico.”

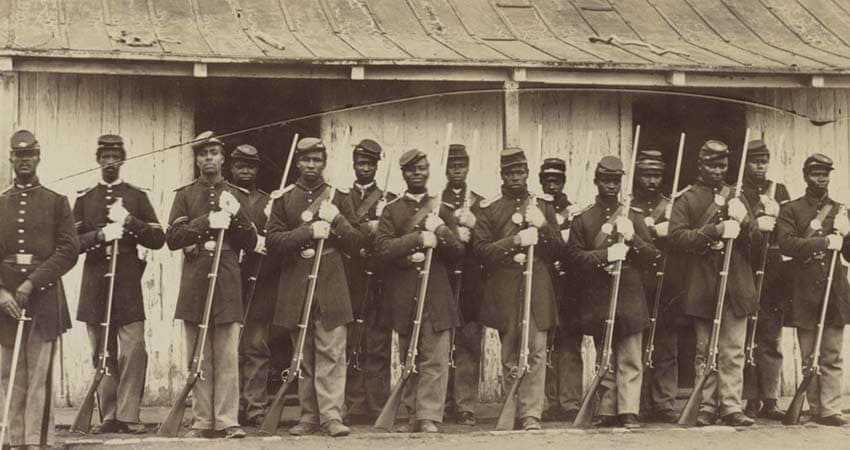

After the Civil War, however, Union forces occupied Texas. These forces – including free Black soldiers – ended up pressuring the French to leave Mexico.

“There were a lot of Black troops in Texas,” Van Hoy said. “It was already a tense situation: the Texans are furious with the 33rd Regiment [of Black troops in the Union army]. The last enslaved people to be freed in the U.S. are Texan… It made things very volatile in Bagdad.”

Some of the Black soldiers fought with the Juaristas in their victory over the imperialistas in the Battle of Bagdad on Jan. 4, 1866. However, the imperialistas reoccupied the port 20 days later with the help of 650 Austrian reinforcements. Bagdad fell to the Juaristas for the second and final time in June 1866, when it was surrendered and evacuated by Mejía, who also relinquished Matamoros.

“It was a turning point, the beginning of the end of the empire,” Van Hoy said.

Following the defeats of the Confederacy and the French, Bagdad shrank in importance and was eventually destroyed by hurricanes.

“Bagdad’s history itself is not very long,” Gonzalez-Quiroga said. “It only lasted 30 to 40 years.”

Yet its heyday blazed with intensity.

“Bagdad was a very huge hot spot,” Van Hoy said. “It was probably the hottest spot in all of Mexico, with Matamoros, for a few months.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.