My first and last names have only four letters each: who could ever get them wrong?

The answer to that question is “almost everyone,” as I discovered while traveling around the world as an itinerant English teacher.

In Saudi Arabia, especially, I was amazed at the imaginative interpretations of my name that I would find on my airplane tickets. One of the most memorable of those moments was when I discovered I was flying from Jeddah to ‘Ar’Ar as June Pintutive.

To make matters worse, Arab speakers are in the habit of transforming all P’s into B’s. So I became Mr. Bint, which my students found wildly hilarious, because in Arabic bint means girl.

Eventually, Mr. Bint arrived in Mexico — now transformed into Señor Medio Litro — whereupon all sorts of new “broblems” arose for getting across his terribly complicated name.

First of all, there is that wayward H in John. Ah, how imaginative Mexicans have been in finding new locations for this useless letter! I am handed my Covid-19 prueba de vacuna and I wonder: what will they turn me into this time? Jonh, Jhon or maybe Hjon?

To prevent such confusion, I first tried clarifying my name with the approach that works in all English-speaking countries: spelling it out: J-O-H-N P-I-N-T.

Now, in Spanish, this spelling process is called deletreo. Contrary to being useful, it absolutely strikes terror into those humble folk who register you when you drive into a fraccionamiento (housing complex):

“Mi nombre es John Pint: jota-o-ache-ene-pe-i-ene-te.”

That even scares me!

Equally disastrous is the “A as in ‘Amsterdam’” approach, especially if you get carried away Mexicanizing it:

Mi nombre es John Pint:

J de Jolostotitlán;

O de Oconahua;

H de Hostotipaquillo;

N de Nejahuete;

P de Pihuamo;

I de Ixtlahuacán;

N de Néxtipac;

T de Tlaquepaque.

Then I smile. What could be clearer than that? But all the while that I was deletreando, the gatekeeper’s eyes were growing wider and wider, and now he seems somewhat paralyzed.

I fear he will have a heart attack right on the spot until, finally, with trembling hand, he gives me his clipboard.

“Y-you write it, Señor … Por favor!”

Spelling doesn’t work well here, and Spanish speakers rarely — if ever — employ it, because they really don’t need it. To clarify the spelling of a word in Spanish, all you do is say the word and comment on whichever letter in it might cause confusion.

“My name is Cortez with a Z.”

“She is Érika with a K.”

“He lives in Huaxtla with an H and an X.”

Getting across your name in Mexico rises to new heights of confusion if you decide to “darte de alta,” that is, to register yourself as a Mexican taxpayer, something I had to do in order to legally sell my books in this country.

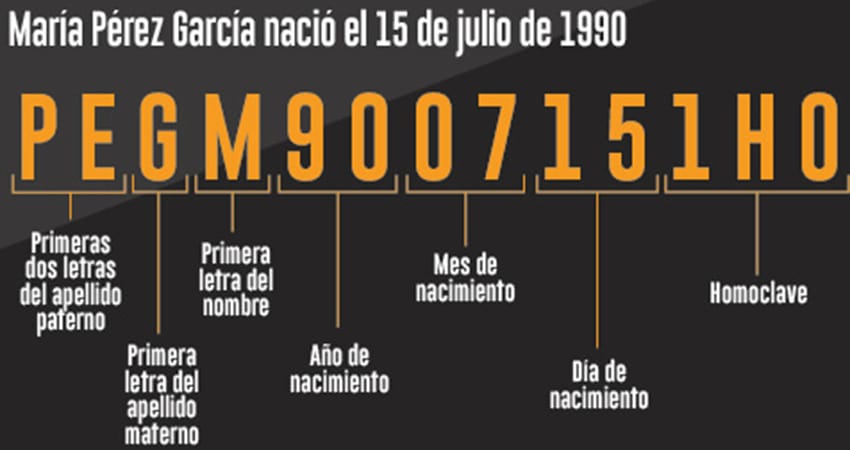

Step No. 1 in this registration process is to get yourself an RFC code, an alphanumeric string of characters identifying you as a Registered Federal Contributor.

The RFC is generated via a truly Mexican formula that is cleverly designed to produce a unique series of numbers and letters to identify you for tax purposes.

This mix of numbers and letters is based on your date of birth plus your name … and that’s where things get interesting, because, as Wikipedia puts it so succinctly but not terribly clearly:

“Full names in Spanish-speaking countries consist of three elements:

Given name(s);

First surname: the father’s first surname; and

Second surname: the mother’s first surname.”

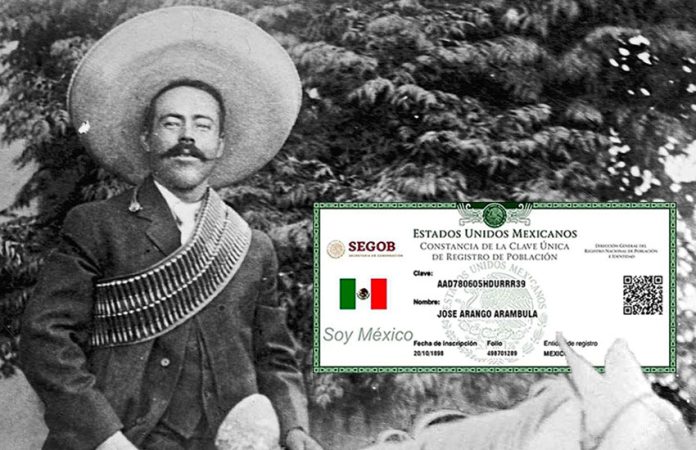

So, if someone mentions a legendary character called José Doroteo Arango Arámbula, it means that this caballero’s first name was José and his middle name was Doroteo. His father, of course, was a man known as Señor Arango and his mother’s maiden name was Arámbula.

Once you get all that clear, you are casually told that, después de todo, everybody called this fellow Pancho Villa.

Many years ago — all naïve — I went to get my first RFC.

“Your name, sir?”

“My name is John James Pint. Let me write it for you so we can save an hour or so …”

Within minutes I was issued my RFC, and not long afterward, I began to get tax-related letters from the government beginning thus:

Estimado Señor James …

A few years later, however, they figured out that James was not really my father’s surname and called me in to get a new RFC, this time asking me for both my father’s and my mother’s last names.

As a result, I got a new RFC, but during the following years, I was called back again and again and ended up issued one RFC after another, each one a little different than the previous.

At last, I decided to “darme de baja,” to unregister as a taxpayer, and that’s when I was told I would have to get a CURP, which stands for Clave Única de Registro de Población, or the Unique Population Registry Code, a yet-more-complicated alphanumeric string that is supposed to identify not just taxpayers but every single person in the country, including foreigners.

Nowadays, you need a CURP to do just about anything.

Once again, I presented myself to a government office and got myself a CURP. Unlike the RFC, this new ID had everything straight in respect to my first and middle names as well as the surnames of my mother and father.

However, just one year later, the powers that be informed me that my perfectly correct CURP was suddenly invalid. “We have a new regulation,” they said. “Mother’s maiden names are now out, and foreigners’ CURPs can only be based on what’s shown on their passports.” That leaves me with a string of six different RFCs and CURPs, and I’m betting it won’t be long before I get lucky No. 7.

Foreigners have problems identifying themselves, but Mexicans, too, are plagued with misinterpretations of their names, especially on vital documents like marriage licenses and birth certificates.

Birth certificates in particular seemed to fall prey to what I call La Ley de Horacio, which states that “if the Registrar of Births can get every single detail wrong, he will.”

So it is a sure bet that when Don Fidelio goes into town to register the birth of his son Hildeberto Móntez Ibarra de la Vega, the registrar will surely write: Ildeberto Montes Ybarra de la Bega.

When it comes to registering the date of little Hildeberto’s birth, I imagine the conversation goes something like this:

“Don Fidelio, when was the baby born?”

“Hace como dos semanas” (Like two weeks ago).

“On Friday two weeks ago?”

“Más o menos” (more or less).

Only when Don Fidelio gets back home, perhaps after a long journey with the birth certificate in hand, does his wife point out that the baby was actually born a bit más rather than menos.

For the next 30 years, Hildeberto will celebrate his birthday on the day his mother says he was born, and that’s what he’ll put on all his documents … until one day he’s asked to prove it with a birth certificate…

That’s when the fun begins.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.