Most Mexico City residents, as well as many tour guides and publications, will absolutely swear that the famed axolotl amphibian can only be found in what is left of the lake system now mostly destroyed by Mexico’s capital. But like so many things in Mexico, that statement is true and false.

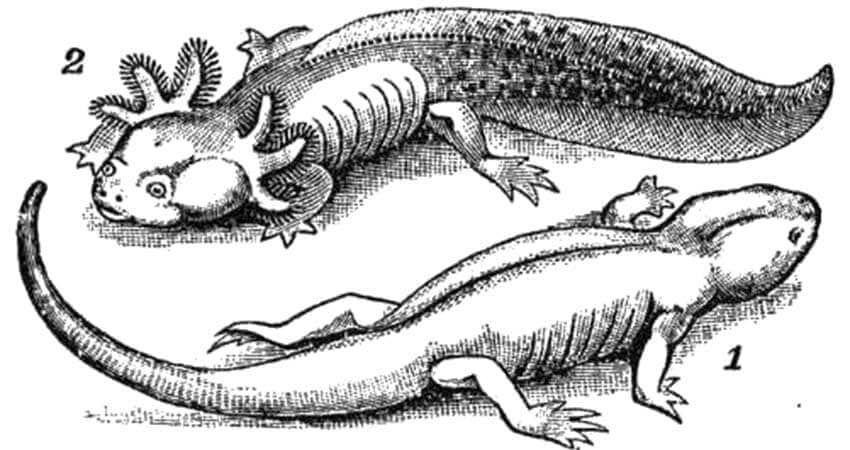

The term “axolotl” in English is generally used for the Mexico City creature, Ambystoma mexicanum, which has lion mane-like protrusions and a wide face with a curious “smile.” It is the one endangered by the capital’s explosive growth and therefore has received the most attention by far — not to mention its very unusual ability to regenerate limbs and even vital organs to an extent.

But 16 members of Ambystoma are endemic to Mexico. Only one, Ambystoma mavortium, or the barred tiger salamander, has a range that extends into the United States and Canada.

All of them can be considered axolotls and/or salamanders but often aren’t because popular naming depends on their region and, frequently, whether the full-grown adult has the “lion’s mane” or not. If you live in one of several of Mexico’s states, you may have seen one and not even realized it because the one in your area looks little to nothing like the ones in Mexico City.

During at least some point in their development, all Ambystoma do have both lungs and gills (the lion’s mane), although depending on the species, the animal might favor one over the other. This depends on how much time the species spends on land.

Other things all these salamanders have in common are a need to keep their skin wet, the fact that they do not shed their skin and the absence of metamorphosis seen in many other amphibians. Coloration varies even among the same species, and albinism is relatively common.

The Ambystoma with the widest range in Mexico is the plateau tiger salamander, found in México state, Puebla, Tlaxcala, Veracruz, Coahuila and Querétaro. But most, like A. mexicanum, are found only in very narrow ranges of area, often just in one small body of water.

In addition to A. mexicanum, there are other axolotls in the Valley of México and the mountains surrounding it. These include the mole axolotl (A. rivulare) in the valley proper. The granular axolotl (A. granulosum) is found only in the streams of the Iztacchihuatl, Popocatepatl and Monte Tlaloc volcanoes on the valley’s eastern edge.

Nearby is the range of A. leorai, the axolotl found only in the town of Río Frio in México state. In Puebla proper, there is the alchichica axolotl (A. taylori), named after the small volcanic lake in Tepehuayo, where it is found.

West of the Valley of México is the Sierra de las Cruces, the habitat of mountain stream axolotl (A. altamirani). Beyond these mountains is the Valley of Toluca, still in México state, where the main axolotl is the Lerma axolotl, (A. lermaense), which survives despite the wretched conditions of the Lerma River.

Also in the state is A. bombypellum, only in the municipality of Tenango del Valle. It is extremely rare.

Over the next set of mountains, Michoacán has several species, but as this was the territory of the Purépecha, the common name for the animal here is “achoque,” rather than the Náhuatl-derived “axolotl.”

Of these Michoacán species, the achoques of Zacapu lake’s scientific name is A. andersoni; those of Lake Pátzcuaro are A. dumerilii and those of the Tancítaro municipality are A. amblycephalum.

To the west and northwest, you’ll find the habitats of the Chapala axolotl (A. flavipiperatum), found in the Sierra de Quila in Tecolotlán, Jalisco; the Tarahumara salamander (A. rosaceum) in the Sierra Madre Occidental; and the pine axolotl (A. silvense) in the Sierra Madre Occidental of Durango.

It is true that just about all Ambystoma are at least somewhat endangered — some so critically that they are all but extinct in the wild.

The main culprit is loss of habitat. The central highlands are by far the most populated and developed part of Mexico, so pressures on land and water are enormous. A. mexicanum not only gets attention because of the capital but also because its habitat was destroyed first, over a process of drainage going on since the colonial period.

But such habitat destruction has not stopped at the Valley of México’s edges. It now extends far beyond Mexico City due to the construction of housing and roads and the pumping of water to urban areas.

Up to 10% of natural fresh surface water in these areas has been lost, and what is left is often a highly-toxic brew of feces, chemicals and garbage that includes introduced species like carp and tilapia that prey on axolotl larvae.

As much as humans have caused the near-extinction of the axolotl, conservation efforts are the only reasons axolotls still exist. The National University of Mexico is most concerned with A. mexicanum as its habitat is very close to its main campus. For the same reason, the México State Autonomous University works with the Lerma axolotl.

But perhaps the more interesting efforts have been private. In 2019, a small sanctuary dedicated to axolotls opened in Zacatelco, Tlaxcala state. It was followed by the Museo Mexicano del Axolote (MUMAX) in 2020 in the state of Puebla.

Even more curious is the work of the nuns at the Basilica of Nuestra Señora de la Salud in Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, who raise and care for over 300 of Pátzcuaro lake’s achoques. It began several decades ago because wild populations were rapidly decreasing, but their motivation was not ecological.

For over a century, the nuns have used a secretion from their skin to make a cough syrup, so a reliable supply was necessary. Today, the nuns have 300 captive animals that are the species’ best bet for survival.

Although axolotls are relatively easy to raise and can live for 10 years in captivity, releasing such populations back into the wild is not yet viable. Raised in pristine conditions, they cannot survive the shock of the polluted waters where they should be in the first place.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.