Yesterday, I received a message from a long-time acquaintance, a fellow immigrant: “What is going on in your expat group?”

I winced and immediately felt irritated, remembering that I am, in fact, the administrator of a local Facebook group.

I inherited the group from another fellow who was leaving Mexico and wanted someone “in-house” to take charge. “You won’t really have to do anything with it, I just thought it would be silly for someone not actually in Mexico to be running it,” he’d said.

I accepted and then pretty much forgot about it along with the rest of Facebook — except for the memes; I’ll always show up for the memes.

That, apparently, was a mistake. Unbeknownst to me, many people had joined this group without me realizing it, requests having been granted automatically for those with Facebook accounts more than two years old. Among those who had joined were quite a few Mexicans.

Some of them simply wanted to offer their services and wares, but a few had a major bone to pick with foreigners in general and found in this group a great place to launch their fightin’ words.

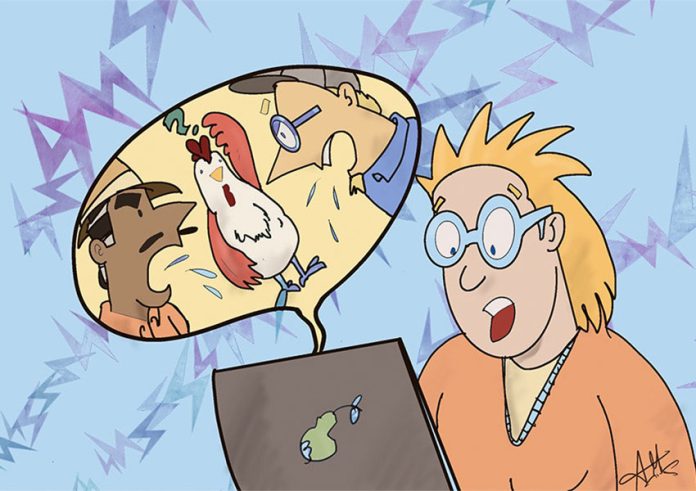

The thing that set it all off was pretty silly: someone was complaining about their neighbor’s rooster, which, if you ask me, is a pretty normal thing for anyone to complain about because roosters are just the worst. Plus, hens will still lay (unfertilized) eggs without them, so I don’t know why people have them in the city at all unless they’re raising chickens.

Anyway.

Before we all knew what was happening, someone had taken a screenshot of the post and put it on Reddit, where many an insulted Mexican piped up with some version of “Who do these freaking gringos (the poster was actually French Canadian) think they are? That’s just like them, telling us how we’re supposed to live, but if we go there, we can’t say anything, can we?” And on and on and on it went, until it eventually became a “news article” of the click-baity type that claimed it was a “viral” story. Sigh.

After that happened, another Mexican who was in the group for unknown reasons made a long, ranting post about how if we didn’t like things here, we could go back to where we came from. He made some very rude suggestions about what we could do to our mothers, and others piled on in the comments. Double sigh.

I quickly deleted the offending posts and banned the authors and for the first time in a while, went through the group’s various posts, looking for and extracting offenders. I re-established the rules and added another administrator — one who was actually excited to be helping with the group — and crossed my fingers that that would be that.

Though it perhaps shouldn’t have, the drama took me by surprise.

The conflicts, of course, weren’t just about an annoying rooster. The conflict was really about history and prejudice and belonging and resentment and immigration and acceptance and duplicity. There are so many complex factors at work when it comes to the host-immigrant relationship, we could probably fill a library with books on the subject.

And as any immigrant in the United States (or anywhere else) will tell you, when you’re an immigrant, you’re officially a representative of the people from your country and are generally lumped in with them, like it or not.

For U.S. citizens especially, this can come as a bit of a shock, as we’re culturally used to being seen as unique individuals — nothing like those other annoying gringos you know.

But everything you do as an immigrant is loaded with meaning. You don’t just get to be a neighbor irritated about someone’s rooster; you’re a gringo who thinks you know everything and wants to tell everyone else how to live their lives, as well as what’s good and what’s bad, and you think you’re better than everybody else — who should follow your rules.

That’s how some people will interpret it, anyway. History itself interprets your behavior, despite what your true feelings and thoughts are.

But as any good therapist will tell you, you can’t control what other people think or feel; you can only control the way you react.

And anyway, Anglos from richer countries are hardly disadvantaged as immigrants in the ways that most other immigrants around the world are. Why, just look at what many of us call ourselves: expats! (I personally do not like or use the term).

“Expats,” among many other things, denotes a person who, rather than humbled to the point of starting from zero in a brand-new place, gets to start from at least 80 in a place where they feel fairly confident and important enough to make demands.

Many of the more recently arrived so-called “digital nomads,” after all, arrive with everything they need to settle into a standard of living that most Mexicans simply do not have access to, no matter how hard they might work; the optics are really not great.

When recently-arrived foreigners scoop up all the best real estate (who else can afford it, I suppose?) and rave about how wonderful their lives here are, it’s easy to see how those unable to enjoy those same perks might feel fairly resentful.

I mean, it sucks to watch people get so much further ahead when you’re just as smart and work just as hard.

The main advantage Mexicans have over foreigners is, of course, the home advantage. They have family support. They can play with and understand the language and culture in a way we never will. They know how things get done.

Also, maybe they can’t afford the most luxurious living spaces, but they have family property where they can live. They might not be able to afford the best hospitals, but there’s someone who can stay by their side in the public hospital, fetching them food and medicines.

We are certainly not disadvantaged. But like immigrants in the rest of the world, it’s nice to have a little connection to home through others that are from where you are. But if you’re going to rant — all of us do sometimes — make sure you’re aware of who’s paying attention and drawing conclusions.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.