The Lacandon jungle is the largest contiguous tropical rainforest left in Mexico and the most biodiverse jungle in the hemisphere after the Amazon. Once part of the heavily populated heartland of the Mayan civilization which flourished in the region and stretching from Chiapas and southern parts of the Yucatán peninsula into Honduras and Guatemala, the jungle is home to an abundance of wildlife.

Toucans, howler monkeys, tapirs and a small population of the critically endangered scarlet macaw call this area of rich ecological diversity home, as well as arguably the most unique tribe in Mexico: the Lacandones.

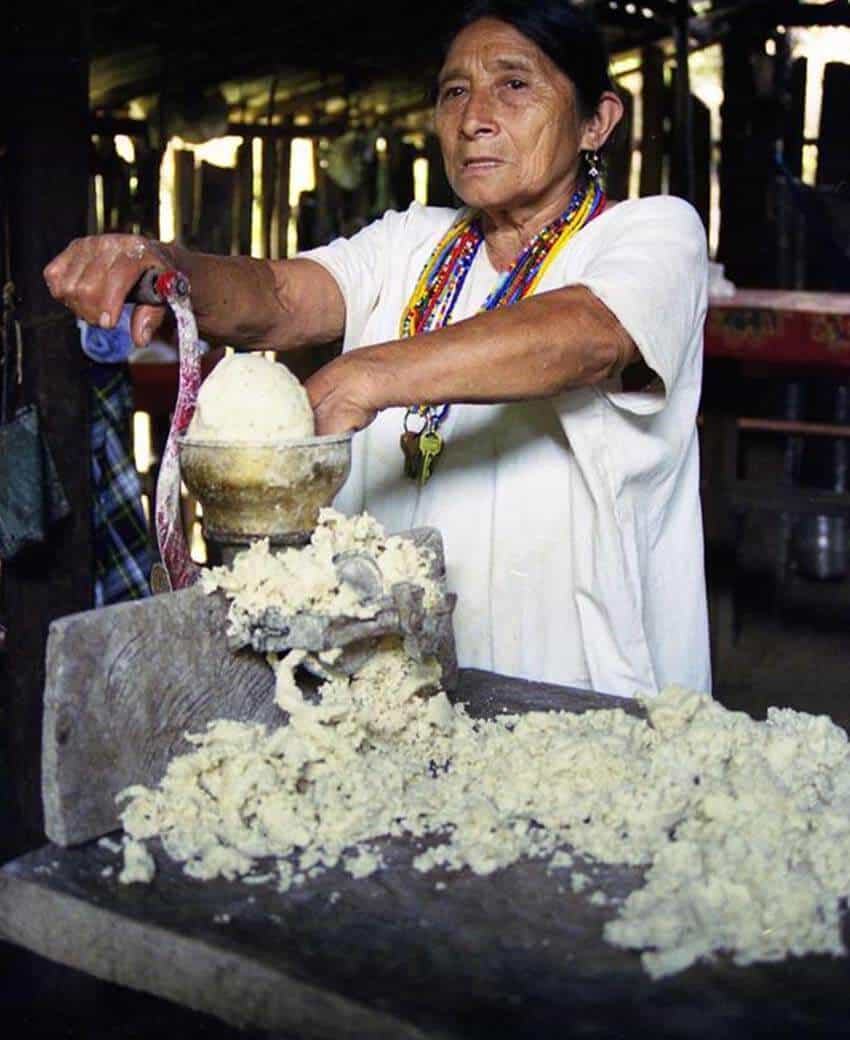

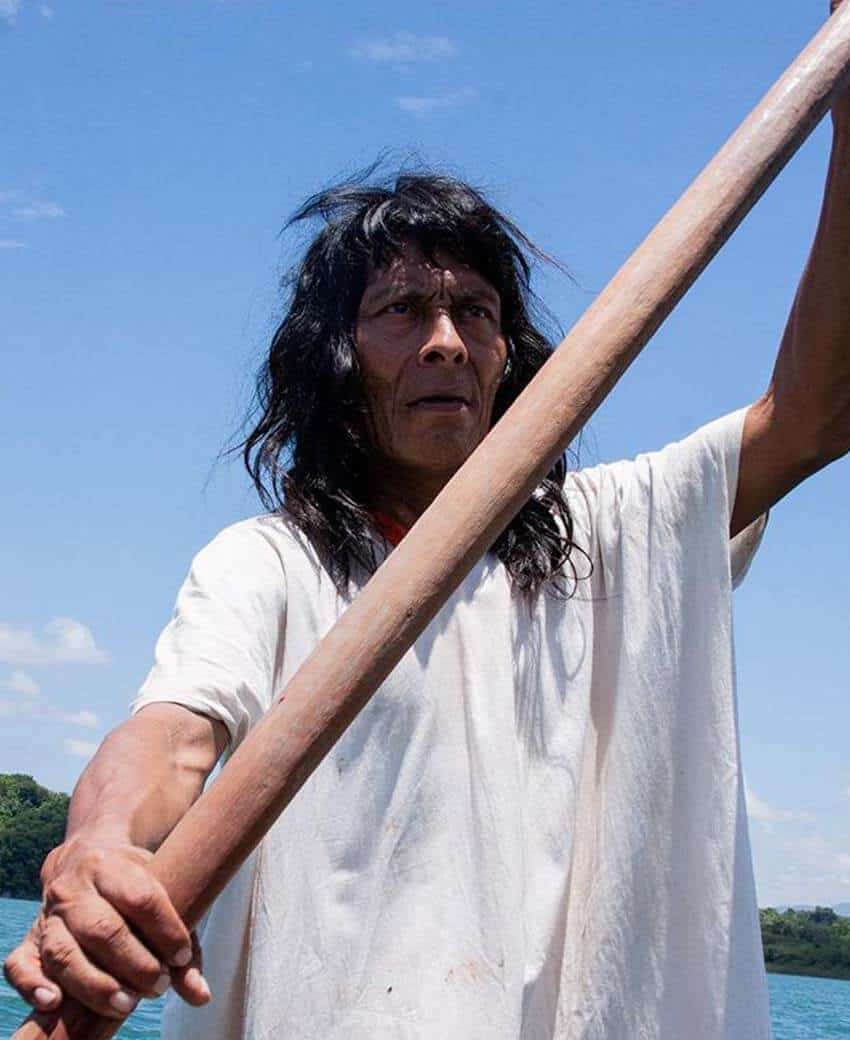

Residing in the vicinity of tributary rivers and lagoons in the Usumacinta River basin, the lifestyle of the Lacandones — known in the Mayan language as the Hach Winik (True People) — is possibly the closest modern approximation we can find to the way the ancient Maya lived — minus, perhaps, the relentless pursuit of new territories.

Speaking about his time spent with them, Mike Alcalde, a documentary filmmaker at México Natural, posits that they are “a people who live in true harmony with nature. Theirs is a worldview which revolves around traditional agriculture, gathering, hunting and fishing; they live by their own traditions and laws.”

Taking only what they need to survive from the forest, the peoples of the Lacandon are unparalleled in their ability to attribute the helpful properties — medicinal or otherwise — to plants. The trails they follow through even the densest parts of the jungle — obscure and undecipherable to visitors — are self-evident to them, and they are able to move through the land without doing harm to its non-human inhabitants.

As a result, they enjoy abundant milpas (fields cultivated for just a few years at a time) growing native corn, beans and other crops, as well as access to water in the rivers and streams.

“The Lacandones are sentinels of the jungle,” says Alcalde. “Their territory is sacred, and they do not allow other communities to harm it. They zealously protect trees, animals and water alike.”

The people of the Lacandon have not always been so isolated in their stewardship of the jungle. In the late 1970s, 3,312 square kilometers of the Lacandon were allocated as a biosphere reserve by the federal government under the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere (MAB) program.

The MAB initiative works towards enhancing relationships between people and their environments. Biospheres are set aside for their genetic significance instead of other considerations such as aesthetics.

However, the protected land area that Mexico established, known as Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, has proven to be a legal fiction. For all the supposed government protection of their lands, the Lacandones are struggling to keep the wolves of extractivism from the door.

Extractivism refers to the process of extracting valuable natural resources to sell on the world market.

Theirs is a rich and flourishing ecosystem, abundant in resources that neighboring communities, as well as large capitalist corporations and the government, are increasingly looking to get their hands on.

The land is historied with such conflicts: like any indigenous tribes at the time of the Spanish conquest, the Lacandones were threatened into near nonexistence hundreds of years ago and have remained under the prolonged threat of newcomers flooding the jungle.

The Lacandon jungle was also the site of major conflicts during the Zapatista uprising of 1994, fueled by colonization, enslavement and the exploitation of indigenous communities across Mexico. Though the Zapatistas claimed to be fighting for indigenous people, the Lacandones were left to worry whether their own battle to recover their stolen land had been doomed by the Zapatistas’ cause.

Compounding this problem, argues Alcalde, are the various side effects that the arrival of modernity invariably has on small, isolated communities. It is a tale as old as extractivism itself: workers on behalf of governments and corporations arrive with their various luxuries and leave behind a polluted legacy that seeps into the workings of communities that have sustained themselves for centuries.

“The arrival of government support instruments, far from benefiting the Lacandon community, increasingly separate it from a way of life that has historically been sustainable,” says Alcalde. “Wrong concepts and strategies, one after another, have led Lacandon communities to begin negative changes in their way of life.”

It is not uncommon today, for example, to see the children consuming the same chemical-ridden, plastic-wrapped fast food that tragically blights populations of all sizes the world over. Perhaps more unnervingly, says Alcalde, are the swish new vehicles cruising the roads, sponsored by automotive companies with vested interests in the land and its resources.

As a result, Alcalde argues, the Lacandones are beginning to lose the essence of that which has distinguished them for centuries.

“The new generations of Lacandones are visibly moving away from the way of life that has sustained them for centuries,” he says. “Fewer and fewer young people are planning to remain in the communities in the future.”

It’s a familiar story, one that repeats itself across Latin America and indeed the world, one involving the loss of language, biosphere, of cultural memory. But Mexico, unlike many other nations, still has these riches to lose.

The Lacandones are a hardy people, ghosts of the rainforest. Their extinction — as with all extinctions — will be a slow one, but it is not too late to give them the protections that they need.

And what protections are those? Alcalde is forthright in his response:

“To be left alone. To be given the power to make their own decisions. To have their land federally protected with serious consequences. To be celebrated, to be trusted. We should be learning from them, not the other way around.”

Shannon Collins is an environment correspondent at Ninth Wave Global, an environmental organization and think tank. She writes from Campeche.