There is a small community outside of Guadalupe, Zacatecas, with the odd name of Tacoaleche, and no, the name has nothing to do with tacos. The name refers to a unit of milk, as it was once common for hacienda owners to pay workers with food rather than money.

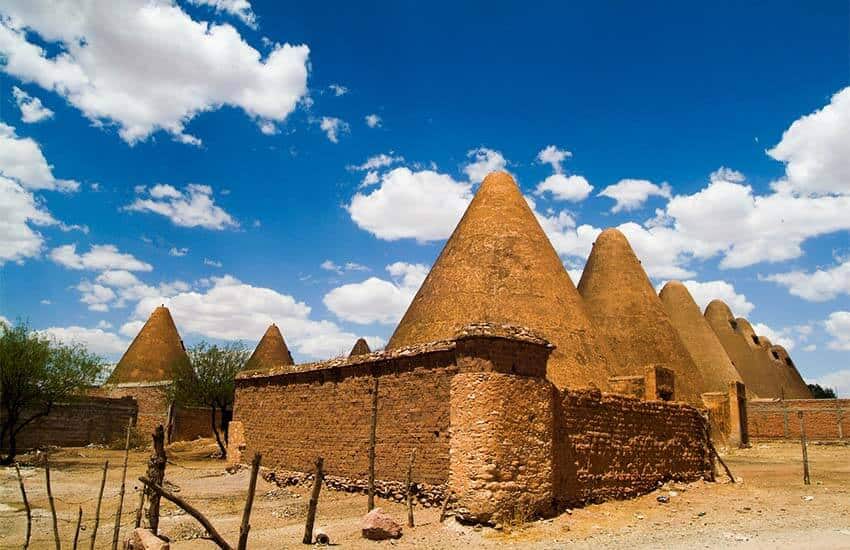

By far the most attractive thing in this dusty town is the so-called House of 100 Doors. Covering a quarter hectare, it is a two-story building of adobe with supports of volcanic tuff stone on the ground floor and metal pillars on the upper floor. A church on the plaza and grain storage facilities, simply called The Cones, were built around the same time.

The house is part of the Tacoaleche hacienda formed in the latter 19th century. In 1880, Antonio García inherited a small portion of a much larger estate that belonged to the Count of Jaral for centuries. Shortly after the inheritance, García not only set up his operations, he also fell in love with the daughter of another hacienda owner.

Here is where the legend begins. Like with most legends, there are variations.

The most common version states that the daughter accepted the proposal but only on the condition that the marriage would occur after he built his hacienda house with 100 doors. In all versions, the marriage never happens with various explanations as to why. The two most common have the girl renege on her promise.

One states that she counted the doors to find that there were not 100. Indeed the house does have “only” 99 doors, with an assertion that the 100th is hidden somewhere on a nearby hill. The other states that she never meant to marry García, making the condition because she thought he would never be able to complete the task. A third, unfortunately, has García kidnapping the girl, then locking her in it, because she cheated on him while he built the house.

The house indeed took a long time to build. It was begun in 1891, but one claim states it was finished in four years, another claims not until 1915.

Some blame the Mexican Revolution for García’s failure to marry, which would make sense if indeed the house took 24 years to complete. Some say that Francisco “Pancho” Villa kidnapped García’s father and uncle for ransom and others say that Villa sacked the hacienda.

Either way, it caused the man to go bankrupt.

It is known that García eventually moved to Mexico City, where he died in 1921. His brothers inherited the property, but the federal government eventually expropriated it as part of land reform.

In 1938, it became the Tacoaleche ejido (land held in common), owned by the hacienda’s former workers. This is when stories about the property’s origin became popular regionally.

The church and square became the center of the community of Tacoaleche. Politically, it is part of the Guadalupe municipality, with its seat in the city of the same name just outside the capital of Zacatecas. But although it is only a 15-minute ride away, Tacoaleche is a world away from the municipal seat.

Like many old hacienda mansions, the House of 100 Doors fell into ruin after everything of value was taken out of it, including the original wooden doors that gave it its name.

While other buildings kept their original purpose, this one was not useful to the new communal owners as a residence. It was used as a jail, a hospital, a school, a movie theater and a party hall before being abandoned completely by the end of the 20th century.

Although García did not die there, there are some rumors that his ghost has been seen at the mansion.

However impractical it might be for local residents, the site is emblematic of southern Zacatecas. The ejido organization began working with arts groups to find a use for the building as well as the funds to restore it.

With over 10 million pesos of support from both the state and federal governments, restoration work was begun in 2007. In 2011, the state opened the Center for Research and Experimentation in Zacatecas Folk Art.

The institution is dedicated to the preservation and evolution of handcrafts and folk arts of the state. It works to research traditional forms and techniques as well as develop new materials, products and more for the state’s artisans. It was founded with a permanent collection of about 200 pieces donated by the federal government, a collection which has grown to over 1,000 works from Zacatecas and other parts of Mexico. The center hosts workshops, sales and academic events.

Although it has been operational for 10 years and is so close to Zacatecas’ only metro area, the folk art center’s location is somewhat odd, and its long-term success is far from assured.

Tacoaleche is considered to be the second-largest community in the Guadalupe municipality, but that is only because of its official population count. In reality, Tacoaleche feels something like a ghost town because so much of its population has migrated to the United States, many of whom never return. Many of the families still there depend on remittances.

Nor are there any nearby hotels or formal restaurants. You pretty much have to go to Guadalupe or Zacatecas city for those. So for those attending events at the center, it is a day trip into the town to participate.

The House of 100 Doors is a good example of the conflicting needs of preserving historical architecture and of the modern realities of the location where historic sites exist. As noble as finding a use for the building is, only the government would put so much money into a project with insufficient local logistics. And at any time, an administration can decide to pull the plug.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.