The prisons cells of an old state penitentiary seem an unlikely place for museum exhibition rooms but that is exactly where you will find the recently opened Leonora Carrington museum in the city of San Luis Potosí.

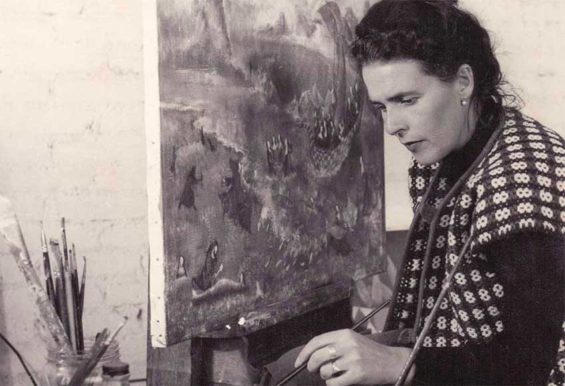

This very surreal setting makes the perfect backdrop for the British-Mexican artist’s work, which drew upon Celtic, Irish and, later, some Mexican folkloric influence to produce fantastical figures and surrealist scenes.

Carrington, who would have turned 100 last year, has seen a recent surge in international notoriety with a number of books about her life being published in the United Kingdom and beyond. Her bronze sculptures adorned Mexico City’s Paseo de la Reforma in 2017 and the Museum of Modern Art inaugurated the exhibition of her work, Cuentos Mágicos, on April 21 to bustling crowds hoping to get the first look.

The Leonora Carrington opened in late March and has seen close to 45,000 visitors already. There is no doubt that the museum is helping to put San Luis Potosí on the map as a tourist destination.

Born in rural England, Carrington came to Mexico in 1942, where she lived and worked until her death in 2011 at the age of 94. Carrington’s early life was spent in rebellion from her upper-class family.

Her love for art started young and she moved to London to study at the Ozefant Academy. In London she met and fell in love with the German painter, Max Ernst, who was married and 26 years her senior, but despite the seemingly large obstacles she ran off with him to Paris when she was just 20 years old. Here she met and socialized with many of the well-known surrealists of the time and her love for the art form was solidified.

While seemingly the ideal muse for the many men of the surrealist movement, she vehemently rejected this position, holding her own and forging ahead with becoming an artist in her own right.

“I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse,” Carrington is quoted as saying. “I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.” When the Second World War broke out, Carrington’s beloved Max Ernst was captured and taken to a Nazi prison camp and Carrington’s deep distress at this led her to be institutionalized.

She escaped by marrying Mexican diplomat Renato Leduc (Ernst, at this point, was free and had married Peggy Guggenheim) and moving via New York to Mexico City, where she divorced Leduc and later married Emerico (Chiki) Weisz, with whom she had two sons.

Her son, Pablo Weisz, was involved in curating the Leonora Carrington museum, and some of his own artwork, which appears to draw heavily from his mother’s influence, is also exhibited there.

Leonora is said to have missed England and continued to drink English tea, served with biscuits, throughout her life in her house in the bohemian Roma neighborhood of Mexico City, where she befriended Spanish artist Remedios Varo and other well-known Europeans. Plans are in place to turn her house into a museum, but opening dates are still unknown.

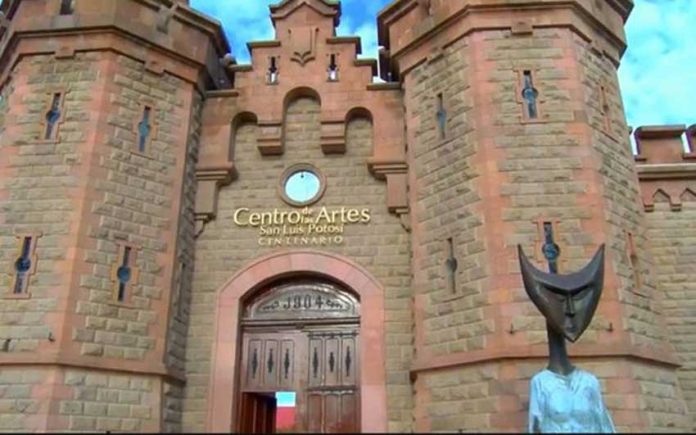

Arriving at the museum in San Luis Potosi, the thick walls and castle-like turrets are the first sign that this museum might be a little unusual. The entrance is via a stunning open courtyard, with bright pink walls that are offset by San Luis Potosi’s impressive skies.

A few of Carrington’s sculptures sit around the courtyard to entice visitors to explore the museum, which is housed in one section of the Centro de las Artes. Once inside, the exhibits are set within old prison cells that now act as exhibition rooms, the Mexican pink walls belaying the fact that this was once the state penitentiary.

Many cell doors have been removed while others have been adorned with Carrington’s fairy-tale-like drawings. The metal staircases serve as a reminder of the building’s prior function and as a result the visitor never quite forgets.

The fact that Carrington’s work is pure escapism seems to sit both in complete contrast and in total harmony with the surroundings.

Carrington was a multimedia artist, something that is made clear when visiting this museum. There are rooms that contain her bronze sculptures in various sizes and others that display her paintings and drawings. Every room is dotted with beautifully lit quotes by the artist that demonstrate her strong character and illustrate just how much her art and the surrealist world that she created were entwined with her very being.

“The world that I paint, I don’t know if I invented it, rather I think it invented me,” one rather telling quote explains.

In addition to her sculptures and paintings, there are two small rooms that hold her silver work behind glass, and include elaborately surrealistic tequila bottles and fantastical figurines. The museum has gone further than just displaying the artist’s work, however, and director Antonio Garcia Acosta and his team got wonderfully creative in collaborating with other visual and sound artists to bring Carrington’s work to life.

The Hall of Mirrors enchants with an animated version of the first part of Carrington’s book, White Rabbits. The animation of the story set on the imaginary Pest Street, directed by Luis Cabrera, illustrated by Richard Zela and dramatized by Beatriz Cecilia, sees ghost-like figures and insects floating from mirror to mirror and is as eerie as it is delightful.

Carrington was also a rather surrealist cook, famously cooking up omelets made with her own hair. The museum has yet to open a café although it is in the plans, but hopefully this kind of culinary masterpiece will not be on the menu.

While it is unknown if Carrington spent much time in the city of San Luis Potosi, she certainly traveled to the state to visit her fellow countryman Edward James. Another surrealist artist and poet, he is best known for his construction of the surrealist garden, Las Pozas, near Xilitla in the tropical Huasteca region. James was a friend and patron of Carrington’s work and Carrington visited Las Pozas often.

It is, therefore, rather fitting that another Carrington museum is due to open in the town of Xilitla within the next few months. The two museums as well as Las Pozas and the ghost town of Real de Catorce will only combine to put San Luis Potosi well and truly on the map as Mexico’s most surrealist state.

Leonora Carrington Museum, San Luis Potosi

- Location: Calzada de Guadalupe 705

- Opening hours: Tuesday-Sunday 10:00am- 6:00pm

- Entrance fee: 50 pesos (free entry on Wednesdays)

Cuentos Mágicos, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City

- Location: Paseo de la Reforma , Bosque de Chapultepec I Secc, 11560 Miguel Hidalgo, CDMX

- Opening hours: Tuesday-Sunday 10:15am- 5:30pm (until September 23)

- Entrance fee: 65 pesos (free entry on Sundays)

Susannah Rigg is a freelance writer and Mexico specialist based in Mexico City. Her work has been published by BBC Travel, Condé Nast Traveler, CNN Travel and The Independent UK among others. Find out more about Susannah on her website.