While studying mineral deposits and rock formations in Sonora, geologist Chris Lloyd and his companions found themselves on a lonely road near the headwaters of the Yaqui River. Eventually, the road dead-ended, apparently in the middle of nowhere. But here Lloyd and his team came upon a campground.

“The campers were hunters,” Lloyd told me, “which I might expect, but the surprising thing was that the hunters were biologists and veterinarians and their rifles contained not bullets but darts.”

Still more surprising was what the men were hunting: jaguars.

“Every year,” Lloyd told me, “these hunters tranquilize the jaguars, weigh them, measure them and see how they are doing.”

That lonely campsite, it turned out, was located inside the Reserva Jaguar del Norte ( Northern Jaguar Reserve), a most unusual jaguar sanctuary: 24,400 hectares in size, with no surrounding fences around it. The biologists told the geologists that they worked regularly with cattle ranchers outside the Reserve, showing them better ways to manage their livestock.

“They’ve convinced them,” says Lloyd, “to create new water holes on their ranch land and not send all the cows off to one common hole where it would be easy for the jaguar just to sit and wait for dinner to arrive. They also reintroduced peccaries and explained to the ranchers: ‘Look, these peccaries are not for you to hunt, they’re for the jaguars to hunt — and then they’ll leave your cows alone.’”

Other strategies suggested to the ranchers include moving cattle to better-guarded pastures and keeping pregnant cows near the ranch instead of out in the middle of nowhere. In some cases the simple construction of scarecrows or the use of cowbells can make a big difference.

Viviendo con Felinos (Living with Felines) is the name of another successful program initiated by conservationists in the area.

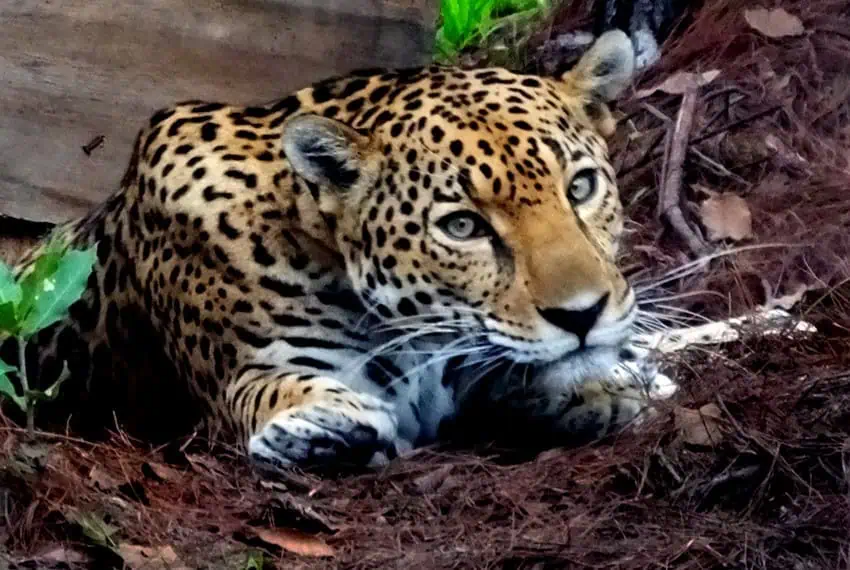

Cats caught by camera trap

Ranchers sign a contract not to hunt, trap or molest the great cats in their area, as well as the peccaries and deer that they prey on. Camera traps are then placed on their properties and the owners receive monthly payments — monetary or in the form of ranch goods — for photos of jaguars, ocelots, bobcats and mountain lions. In some cases this could add up to as much as 20,000 pesos per month, allowing some ranchers to stay in Mexico instead of being forced to seek work in the United States.

The photos of cats, taken on ranchers’ own properties, have impacted participants in this program. Some have named the feline visitors after their own children. Some have given them honorifics: Doña Eduarda, Don Julio and Don Pablo, for example. Thanks to the photographs, unknown potential threats have been transformed into welcome new members of the family.

Birth of the Sonora jaguar sanctuary

After years of pioneering work in Sonora by researchers like Carlos López and David Brown, authors of the book “Borderland Jaguars,” the Northern Jaguar Reserve became a reality in 2003, when Mexican NGO Naturalia purchased Rancho Los Pavos, which is 4,000 hectares in size.

Naturalia was founded in 1990 under the leadership of Dr. Bernardo Villa, a researcher at the Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), to protect and conserve wild species and ecosystems in Mexico.

I asked Naturalia wildlife biologist Saúl Amador how they managed to raise the money to buy their first ranch land.

A little help from African Safari and Leonardo

“To purchase Rancho Los Pavos,” says Amador, “we held a campaign in Mexico City and other places, asking for donations. It was a big success! We received help from everywhere, including organizations like African Safari. On top of that, the Bank of Mexico created commemorative silver coins, whose sales really helped this project. Today this kind of support continues, as we expand the Protected Area. For example, the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation is helping us buy and register our most recent properties: 1,800 hectares, which will become the Babizalito and Carrizal reserves.”

Once Naturalia had bought the land and removed the cattle, the biologists initiated measures for conservation.

“Using camera traps,” Amador told me, “we observed not only jaguars but ocelots and pumas, as well as these animals’ prey, such as the collared peccary, whitetail deer and wild turkey.”

From desert tortoises to military macaws

Today, the species protected inside the Northern Jaguar Reserve include the neotropical river otter, badger, coyote, rattlesnake and desert tortoises, not to mention native bird species like the bald eagle, elegant trogon and military macaw. On top of that, the reserve is a stopover for migratory birds like the Cooper’s hawk and the willow flycatcher.

In other parts of Sonora, Naturalia works in the enchanting Sierra de Álamos-Río Cuchujaqui Biosphere Reserve, which covers almost 93,000 hectares and hosts a wealth of key species like puma, jaguar, ocelot and kinkajous.

The organization has also been working for seven years with Yaqui people in the Sierra del Bacatete reserve, helping them carry out big cat monitoring on their land and showing the community how to use camera traps.

Jaguars and ranchers walking together

“What are your plans for the future?” I asked Amador.

“Our new project,” replied the biologist, “is called Operation Jaguar. We want to replicate our Sonora successes in other parts of Mexico, starting in Nayarit and the Yucatán Peninsula. It’s the same idea. We want to talk to ranchers, not about eliminating cattle ranching but modifying some of their practices, which will also benefit their work.”

One Sonoran rancher summed up this unusual conservation project nicely: “We can achieve a balance between ranching and the preservation of native species. Jaguars and ranchers will walk together.”

John Pint has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.