This year marks the 220th anniversary of the only chemical element ever discovered in Mexico to date — vanadium.

Spanish-born scientist Andrés Manuel del Río made the discovery in 1801, but due to a controversy over whether or not it was a new element, he never quite got full credit throughout much of history.

More recently, del Río has gained posthumous recognition for his achievement — including an annual prize named after him, which is given to Mexico’s top chemist. As for vanadium itself, it has been used in the modern era to make stronger steel and more durable cars, even helping to pave the way for the nuclear age.

The story begins in the late 18th century, when del Río came to Mexico, which was then part of the Spanish Empire. After receiving a first-class education across Europe, del Río went to Mexico at the behest of the Spanish crown as a faculty member who would assist the new Royal School of Mines, housed at Mexico City’s new Palace of Mining.

“[He was] sent to New Spain because he was the best mineralogist in Spain,” said Omar Escamilla, an archivist at the Palace of Mining. “The School of Mines in Mexico was the most important for the whole Spanish crown since silver was a very, very important natural resource to sustain [it]. The best people were sent to Mexico City in order to open the School of Mines.”

It was in that capacity that del Río received a mysterious sample of ore from Zimapan, Hidalgo, in 1801. He initially concluded that it was a kind of brown lead. Yet, he eventually posited that it was a new element, first terming it erythronium then panchromium because it turned many colors when heated.

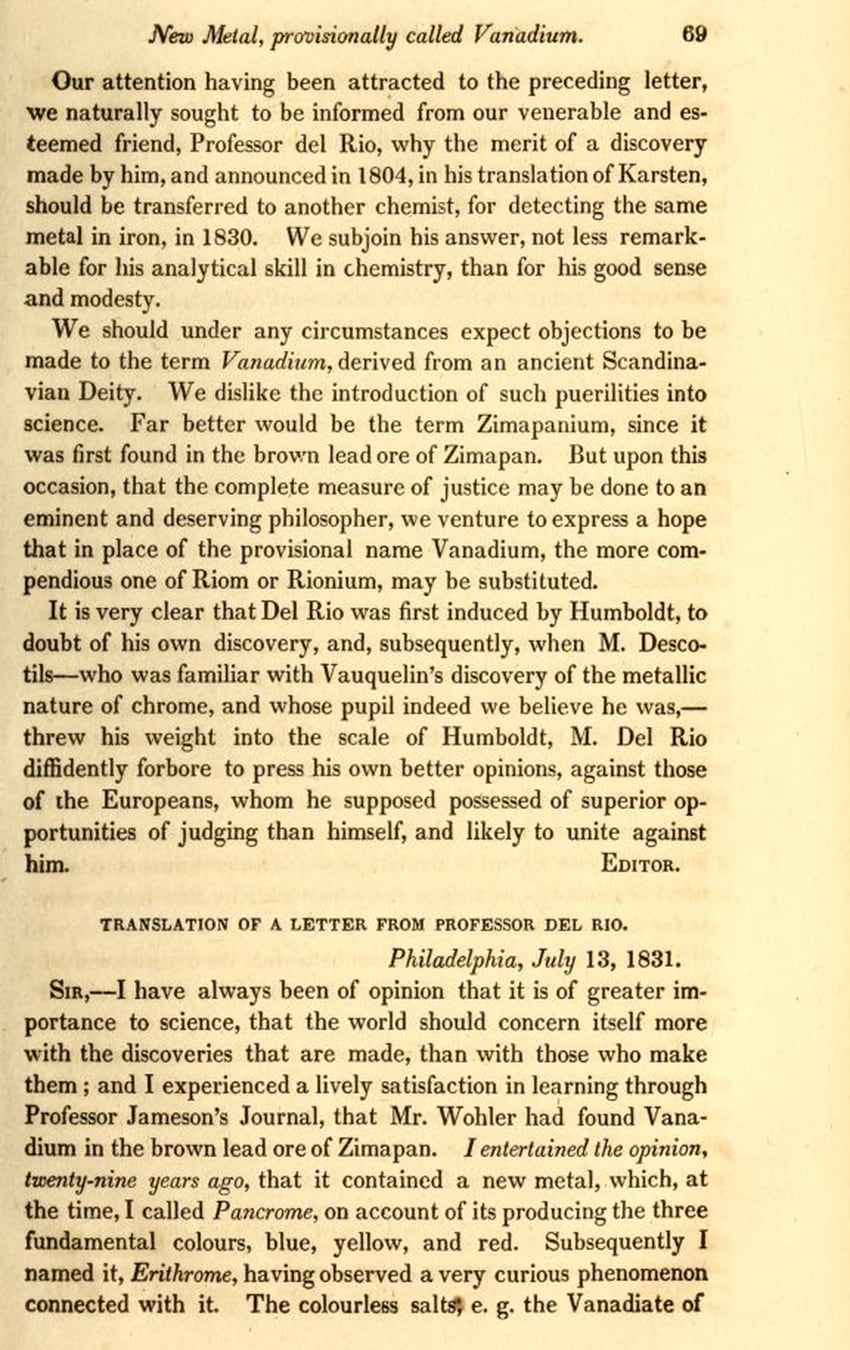

A few years later, in 1803, he gave some of the ore to the celebrated German botanist Alexander von Humboldt to take to Europe. Von Humboldt shared it with a respected colleague, French chemist Hippolyte Victor Collet-Descotils. Ultimately, Collet-Descotils concluded that del Río’s find was not a new element.

“There was no reason to doubt [del Río’s] initial conclusion that it was a new element,” said Rocio Gómez, a professor of history at Virginia Commonwealth University who gave a talk about del Río while at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia. “This is a man who studied mineralogy extensively for decades.”

Later, in 1830, Swedish scientist Nils Gabriel Sefstrom discovered a sample of copper ore from the Eckersholm Mine in his home country and proclaimed that it was a new element. He named it vanadium, after the Norse goddess of beauty.

When others learned of the discovery, they remembered del Río’s earlier find — including von Humboldt and another German scientist, Friedrich Wohler. The latter compared Sefstrom’s findings with del Río’s previous findings and found them to be the same.

Despite the fact that del Río had made the initial discovery, Sefstrom got the credit — and his name for the new element stuck.

By then, del Río had left Mexico. The War of Independence had upended his life.

In the years preceding the war, he had established a precedent-setting ironworks in Michoacán, but it burned down in 1809; the war led to the destruction of the remnants.

After Mexico achieved independence, many intellectuals were expelled for presumed ties to the Spanish crown. Although del Río was not accused himself, he left in 1829 out of solidarity with his colleagues and found a home-in-exile in the U.S.

“He decided to go to Philadelphia because it was a very intellectual, forward-thinking city,” Escamilla said. “He made some friends there in Philadelphia. Some of the friends wanted to call [the new element] Ríonium because of him.”

By 1834, del Río had returned to Mexico and remained there for the rest of his life. He taught mineralogy as a professor at the Royal School of Mines until his death in 1849. According to Escamilla, del Río was initially upset with Humboldt for not coming sufficiently to his aid in trying to prove his discovery of a new element, but the two reconciled later in life.

In the next century, researchers kept finding new uses for vanadium. It contributed to the steel and automotive industries — and indirectly to the nuclear age.

Joel Lubenau, a former advisor to heads of the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission and an ex-national security consultant, said that vanadium worked well as an alloy with steel. A Pennsylvania-based business headed by two brothers, James and Joseph Flannery, used this to their advantage when teaming up to help produce cars for Henry Ford.

“Metal fatigue was a big issue when automobiles started becoming more available,” Lubenau said, noting that incorporating vanadium “made the steel more resistant” and lighter in weight overall. He called the Flannerys “fortunate enough to link up with Henry Ford,” who “was also interested in vanadium steel … It all worked out very well for them.”

The Flannerys’ headquarters were in the Vanadium Building in Pittsburgh, graced by a stained-glass window depicting the element’s Norse goddess namesake holding a plaque bearing the element’s name, among other imagery. The window currently is preserved at the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh.

According to Escamilla, vanadium is one of three elements discovered by a Spaniard, with the others being wolfram/tungsten in 1784 and platinum in the 20th century, and it is the lone element discovered in the Spanish territories of the New World. Escamilla added that del Río’s find was “really an early discovery,” with just 20 to 25 known chemical elements at the time.

“There has been a push over the last few decades in Mexico to have him credited side by side with Sefstrom,” Gómez said, adding that many research bodies “would put Andrés Manuel del Río and Nils Sefstrom side by side. Unfortunately, shared credit did not happen until, of course, del Río had long since passed.”

As another means of honoring del Río, the Chemical Society of Mexico awards an annual prize to scientists in his name.

“He’s one of the notable persons in Mexican mining history,” Gómez said. “He really put Mexican mining in a global context.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.