There are over 1,400 species of bats in the world but only 350 kinds of dogs. You are probably acquainted with quite a few of the dogs, but how many species of bats have you seen?

If you are like most people, you have probably never had a good, close, eyeball-to-eyeball look at even one bat in your entire life. Neither did I until I took up cave exploring as a hobby and then suddenly found myself thrown into the world of bats.

One of the first things I learned was that bats often turn off their famous echolocation systems when they’re hanging around a cave that they consider home … much the same as we might walk to our bathroom in the middle of the night without bothering to turn on a light.

How would you feel if you bumped straight into a large body while walking — all in the dark — toward your bathroom door?

Well, that’s what happens when a bat discovers a caver inside its home. After a few collisions, I learned that you have to let the bats know that there’s an intruder in the house … Yes, perhaps by singing a little song while squatting at the entrance to a bat passage until the inhabitants have had a chance to notice your presence.

Most people only see bats from a distance, as fleeting shapes, silhouetted against a night sky, but as a caver, I got a glimpse of them as social beings.

In La Cueva del Chapuzón, the closest big cave to Guadalajara, we crawled along a long narrow passage that ended at a high point near the ceiling of a big room. By chance, there was a long narrow fissure in the roof of the room, through which a few rays of sunlight happened to be falling upon a bunch of bats hanging from the ceiling only two meters from the spot where we were observing them.

This meant that we could see them right in front of us without using our lights, and for over an hour, we sat there on our little balcony, our feet dangling inside the room, totally entertained as we watched the antics of those bats.

They were grouped into clusters: family units? circles of friends? bat chats? I don’t know, but If you think bats spend all day sleeping upside down, you are wrong. These little creatures were full of energy and very busy doing whatever they were doing … and then we spotted Lonesome George.

George the bat would move from group to group, obviously trying to participate in the action. With great difficulty, he would push himself into one wiggling and jiggling mass of bodies, disappear for a minute and then suddenly pop back out.

“They don’t like him,” we whispered; but George, undaunted, would simply move to the next cluster of bodies and push his way right in, only a minute later to be ejected like a cassette tape (remember those?). George, however, was in no way inclined to give up, and we were all soon rooting for him as he approached yet another social unit.

Years later, thanks to a gizmo that lowers bat frequencies to human audio levels, we discovered that all this frantic activity is accompanied by the bat equivalent of raucous chatting, laughing, complaining and frequent shouting to someone all the way at the other end of the room. Caves are thought of as quiet places, but if there are bats in it, it is about as quiet as a fiesta celebrating Mexican Independencia.

So we began to suspect that bats were far more interesting creatures than we had ever imagined, and this was confirmed when we came upon Archie.

Archie was a baby flying fox whose mother had been electrocuted on power lines in Australia. When her body was removed from the wire, it was discovered that she still had a baby clinging to her — and it was alive, cold and thirsty.

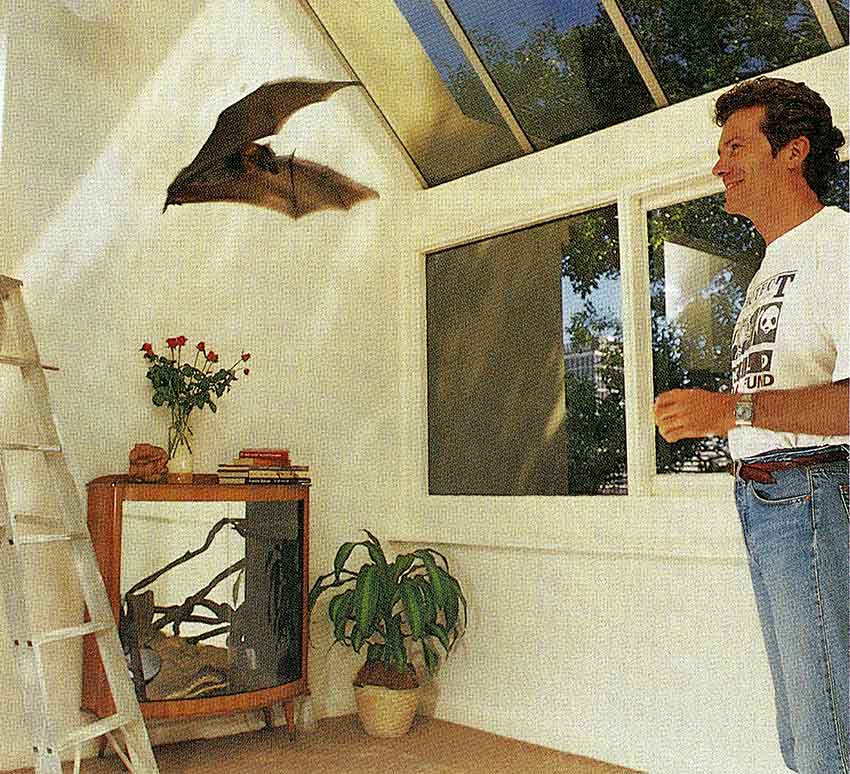

Archie was given food, kept warm and soon handed over to a volunteer foster parent: Richard Morecroft, a TV newscaster who tells the story of what happened after that in his book Raising Archie, published in 1991 by Simon & Schuster.

Morecroft’s story is funny and heartwarming. He describes feeding and washing his little flying fox, as well as changing its diaper, taking it to the post office to be weighed and, three months later, teaching it to fly.

Because the baby bat required constant care at the beginning, Morecroft had to take it to the studio where he worked. There, wrapped in a handkerchief — a substitute for its mother’s wings — it would occasionally wiggle under his shirt as he read the news every evening.

![]()

Thanks to the author’s media connections, the book has 54 delightful photographs, and it’s difficult to believe any human could page through it without falling in love with this little creature with big, beautiful eyes.

The photos of Archie contrast dramatically with the pictures of bats that used to appear in textbooks and encyclopedias before 1982. Typically a researcher would catch a bat in a net, disentangle it and hold it by its outstretched wings as a colleague snapped a photo of the utterly terrified struggling creature who showed its teeth to what it could only presume were predators about to devour it.

But then in 1982, Merlin Tuttle, the much-beloved face of the Milwaukee Public Museum, left his comfortable position and moved to Austin, Texas, to found Bat Conservation International.

Tuttle knew all too well that bats were considered all over the world as terrifying shadows in the dark: rabid rats with wings. He also knew that they were really peaceful creatures as smart and loving as dogs and that neither the planet nor the human race could possibly get along without them.

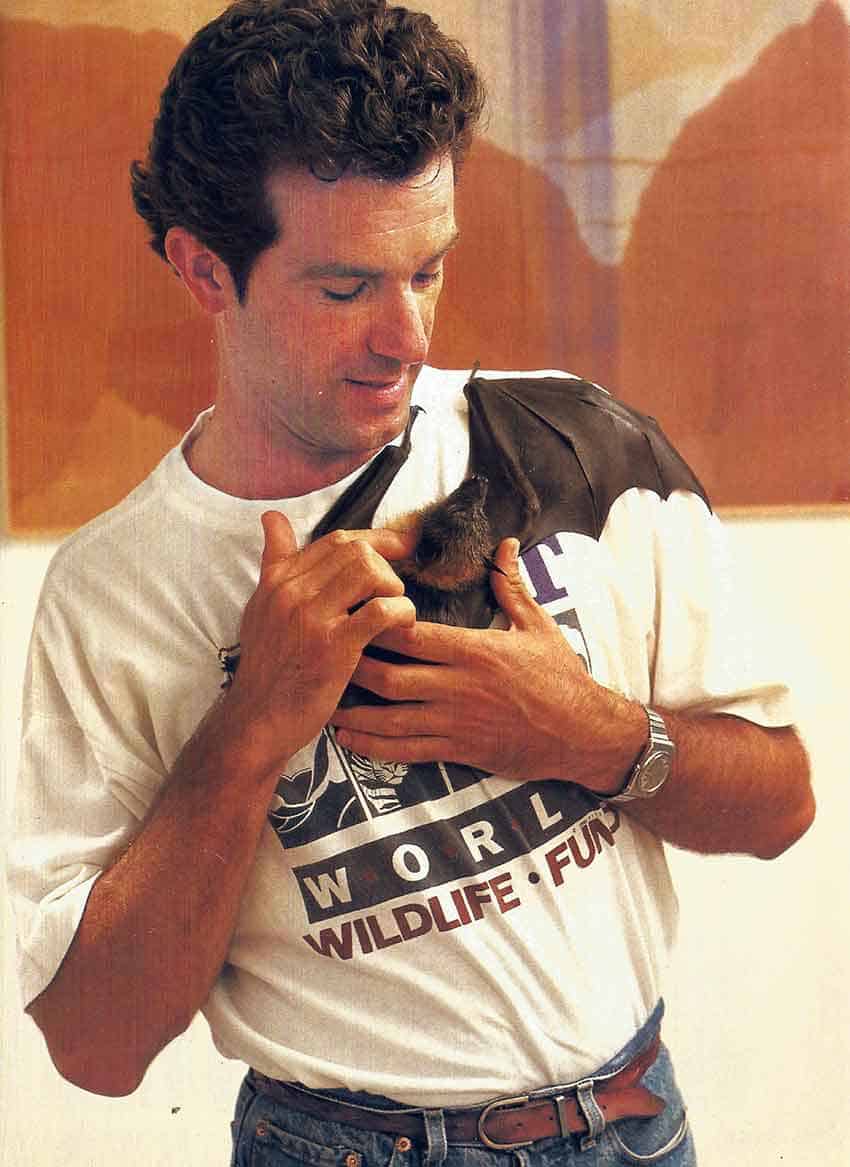

Realizing that what bats most needed was a public relations agent, Tuttle set out to help them change their image. Besides writing numerous articles for National Geographic, Tuttle devoted endless hours to photographing bats as they normally look while going about their business of pollinating plants, controlling insects and dispersing seeds.

He accomplished this by taking the bat out of the net, calming it down, finger-feeding it and then training it to cooperate with him inside a large studio that he would set up in the jungle, on a mountaintop or inside a hotel room.

Since bats are so clever, it might take only a day or two before they would, for example, fly on cue to the upper tip of a cactus (lopped off and stuck on a pole) to pollinate its recently opened flower.

To get a picture of just one bat doing its thing, a picture worthy of Nat Geo, Tuttle would take as many as 10,000 photos. This, of course, was in the days before digital photography, when photographers might spend hours deep inside a cave with no idea if even one of their pictures might be a winner.

In his book The Secret Lives of Bats, Merlin Tuttle describes his modus operandi:

“The next evening, my assistants set nets at a fruiting fig tree in the Kakamega Forest [in Kenya] and caught three Wahlberg’s epauletted fruit bats,” he writes. “These readily accepted food from my hand. Night after night, I virtually lived with my bats until I could call any one of them to my hand, pick them up, carry them around, even wipe a dirty face with a tissue.

“As with all bats, each had its own personality and intelligence, and some would permit liberties not accepted by others. Knowing their individual personalities was essential.”

The short shrift that bats usually receive was frequently on my mind as a cave explorer because it didn’t take me long to discover that in many parts of rural Mexico there is a “war against bats” taking place, which I hope to describe in a future article.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.