Twenty years ago, as a high school student in the United States, mapping out my future, Mexican universities never crossed my mind. I lusted for the fancy schools on the U.S. East Coast — in New York City and Boston, or their glamorous European counterparts in London or Paris. The geography of prestige pointed north and east, never south.

I got my wish: New York University accepted me, and I spent several years immersed in the New York City scene, absorbing everything that an expensive American education promises: intellectual rigor, professional networks, the intoxicating energy of a global city.

It was a wonderful experience, but it broke the bank and sent me through the spiral of New York City extremes: late nights, hustling ambition, ruthless competition — and some intense partying. When I look at my student loan balance today, I can’t say there are no regrets.

Now, decades later, I find myself on the other side of the equation, as a college professor running a business in Mexico City. I’ve started asking questions I never thought to ask as a teenager: What does higher education look like here in Mexico? What is the price range? What programs are Mexican universities strongest in? How are schools here different from universities around the globe? And, perhaps most importantly, how are these schools regarded internationally and in the workplace?

The landscape of Mexican higher education

Mexico has 1,250 registered universities serving a nation of 128 million. At the apex sit institutions largely unknown to Americans but integral to Mexican society and Latin American academia.

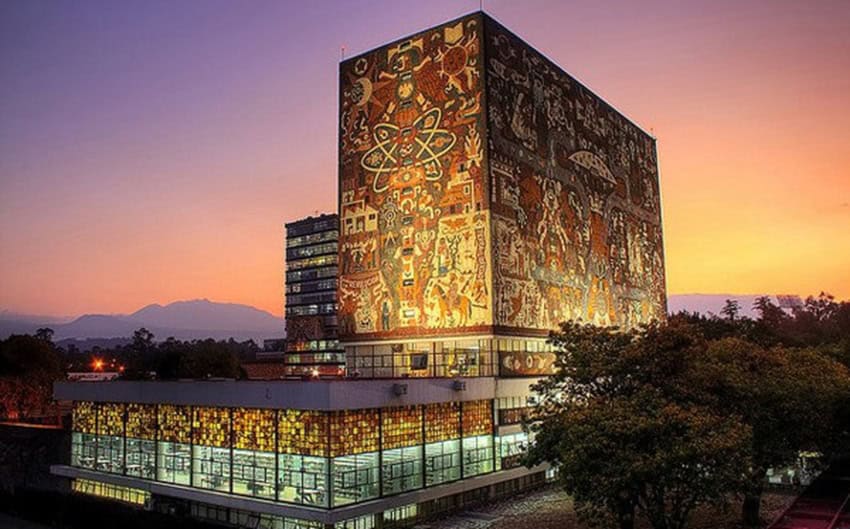

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) is a giant: Founded in 1551, it’s one of the oldest universities in the Americas and enrolls over 350,000 students. Its brutalist architecture main campus, a UNESCO World Heritage site, sprawls across former lava fields in southern Mexico City. This is where Mexico’s presidents, intellectuals and Nobel laureates have been educated for generations.

Then there’s Tecnológico de Monterrey, known as “el Tec.” Founded in 1943 by Monterrey industrialists, it’s Mexico’s premier private university, with 26 campuses nationwide: Think Mexico’s Stanford, focused on innovation and entrepreneurship.

The Instituto Politécnico Nacional (IPN), founded in 1936, serves as the public counterpart, specializing in engineering and technical fields. The Metropolitan Autonomous University (UAM) in Mexico City focuses on social sciences and humanities. Private institutions like Universidad Panamericana and Anáhuac University cater to upper-middle-class families seeking Catholic educational values and smaller class sizes.

Yet by global metrics, Mexican higher education remains invisible. Not a single Mexican university appears in the top 100 of the QS World University Rankings or the Times Higher Education World University Rankings for 2025–2026. UNAM has slipped to No. 136 on QS’s rankings. Tec de Monterrey ranks seventh in Latin America, but No. 187 worldwide. Compare this to MIT’s near-perfect scores or Oxford’s century-long prestige and the gap between Mexico’s universities and these academic titans seems unbridgeable.

The price of prestige

Undergraduate programs in Mexico paint an encouraging picture: UNAM charges a symbolic cuota of approximately 0.25 pesos (practically free) per year, plus minor fees like 490 pesos for the admission exam. For many Mexican students, it’s highly accessible. IPN operates similarly, with semester fees around 400 pesos, making technical education accessible to working-class families historically locked out of professional careers.

The private institutions tell a different story. Tec de Monterrey charges around 350,000 pesos (about US $19,600) annually; expensive by Mexican standards but accessible to the growing middle class via scholarships. Universities like Anáhuac and Panamericana reach around 150,000-200,000 pesos (about US $8,500–$12,000) per year.

Even at the high end, these prices seem quaint. A single semester at NYU now exceeds $60,000. Full cost of attendance pushes $90,000 annually.

This creates a paradox that global rankings can’t measure: accessibility versus prestige. While I was accumulating debt that takes decades to repay, Mexican students were earning degrees for a fraction of the cost. The question becomes: What is that prestige worth?

Why the rankings gap persists

The machinery of global university rankings operates on assumptions that favor wealthy, English-speaking institutions. Statistics such as research volume and the number of academic citations per faculty member carry enormous weight. Many of these metrics require sustained funding, international collaboration networks and publication in high-impact English-language academic journals. Mexican universities, operating with tighter budgets and publishing primarily in Spanish, find themselves automatically disadvantaged.

Internationalization presents another barrier. Elite institutions assemble diverse student bodies and faculty from around the world. Mexican universities serve primarily Mexican students, a model that makes a great deal of sense for a national education system but reads as provincial in global metrics.

Reputation perpetuates existing hierarchies. Academic and employer panels recognize names they already know: Harvard, Oxford, the Sorbonne. It’s a self-reinforcing cycle where prestige begets prestige.

What rankings miss

Yet Mexico’s academic world reveals what rankings cannot capture. UNAM houses world-class researchers in fields from astronomy (it operates major telescopes) to anthropology (its scholars lead excavations of pre-Hispanic sites).

Tec de Monterrey has pioneered educational models focused on entrepreneurship and practical innovation, emphasizing problem-based learning and industry partnerships. IPN has educated generations of Mexican engineers from modest backgrounds who went on to lead the country’s industrial development.

These institutions serve their own societies in deeply impactful ways. They train the doctors, engineers, lawyers and teachers that keep a nation functioning. They conduct research on local problems — water management, earthquake engineering, Indigenous language preservation — that might not generate citations in international academic research but that matter to millions.

The broader question

This raises questions about how we value education globally. The rankings industry has created a monoculture of aspiration, where universities worldwide chase the same metrics, often at the expense of contributions to their local communities. These universities pour resources into attracting international students and faculty, into publishing in English, into research areas favored by citation indices, all to climb a few spots on a list that may or may not correlate with actual educational quality.

Meanwhile, the debt crisis in American higher education continues to worsen. The average U.S. student now graduates owing nearly $30,000, and many owe far more, whereas a Mexican student who graduates from UNAM debt-free, with a solid education and connections to their country’s professional networks, may well have better long-term prospects than their American counterpart drowning in loan payments despite a degree from a “better” institution.

Looking forward

As I advise my own students now, I find myself questioning the assumptions I never thought to question at their age. The global higher education system measures international visibility but not local impact, research citations but not teaching quality, prestige but not accessibility.

Mexican universities may not currently crack the global top 100. But perhaps that says more about the limitations of our ranking systems than about the quality of education these universities provide. In a world increasingly questioning the sustainability of elite higher education’s cost structure, institutions that deliver quality education affordably might represent the future.

Monica Belot is a writer, researcher, strategist and adjunct professor at Parsons School of Design in New York City, where she teaches in the Strategic Design & Management Program. Splitting her time between NYC and Mexico City, where she resides with her naughty silver labrador puppy Atlas, Monica writes about topics spanning everything from the human experience to travel and design research. Follow her varied scribbles on Medium at medium.com/@monicabelot.