On April 4, 2023, at the age of 74, Mexican botanist Dr. Miguel de Jesús Cházaro Basañez died peacefully at his home in Veracruz, while reading a book… on plants, of course.

Cházaro loved plants all his life. When, years ago, his university heard that one of the most famous botanists in the world, Dr. Hugh Iltis, was coming to visit Veracruz, they appointed young biology-student Cházaro as his guide out in the field.

As they were walking along, the story goes, Iltis would say, “I wonder what plant this is?” And Cházaro would tell him the scientific name.

“And what about that one?” And Cházaro knew the name.

At the end, it seemed Iltis couldn’t find any plant that Cházaro didn’t already know quite well. As a result, he invited the young student to get his master’s degree at the University of Wisconsin, launching Cházaro’s career.

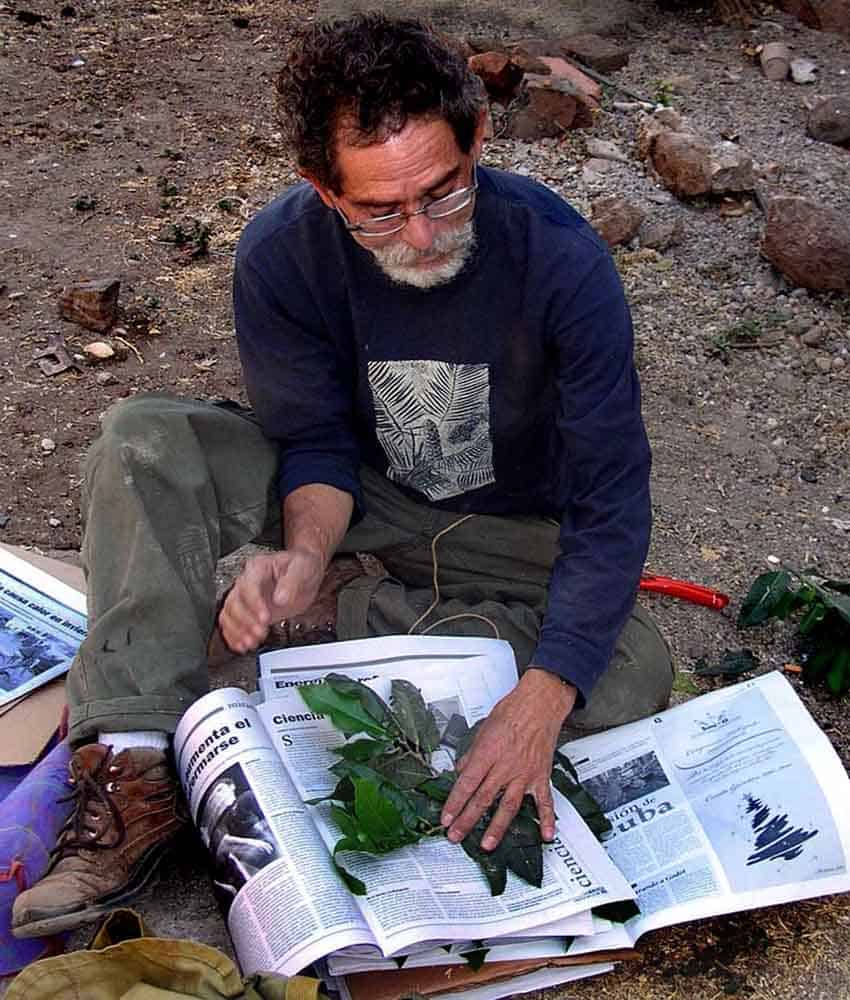

During that long career, Miguel Cházaro discovered and described 18 previously unknown plant species — 10 of them agaves — and his work was so well respected among his colleagues that eight species are named after him.

Estimates say that Cházaro was involved in finding one-third of all the species of cacti that have been discovered since the Spanish arrival in the early 16th century.

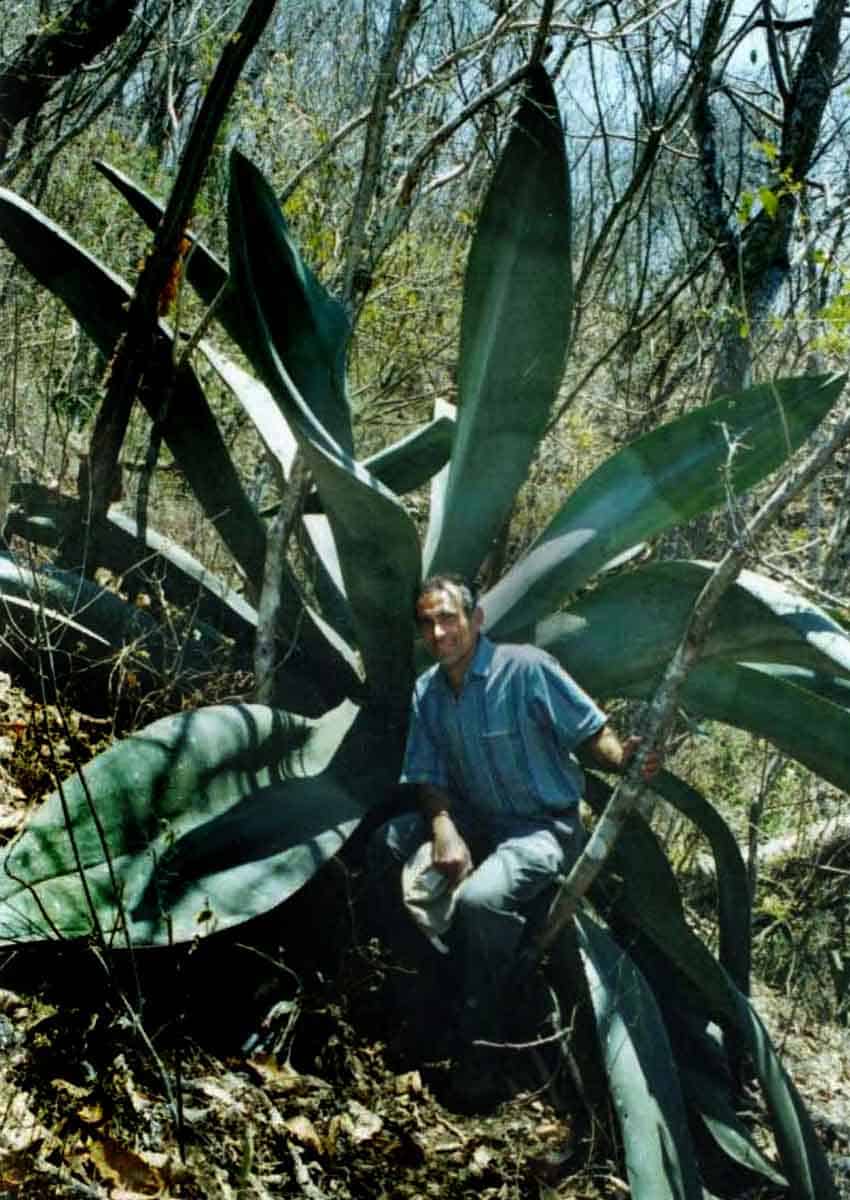

One of Cházaro’s most celebrated discoveries is the maguey relisero (Agave valenciana), a gigantic century plant that he found growing in a remote spot near Jalisco’s Mascota River. When the plant is fully mature, it produces a quiote (flower spike) 6 meters tall with clusters of golden blooms loved by nectar-eating bats.

Cházaro named his discovery after Oscar Valencia, a local plant expert who was completely self-taught. The massive heart of this agave — which is now considered critically endangered — was highly prized by distillers of raicilla, a traditionally made mezcal popular in the western Sierra Madre Occidental.

I met Cházaro in 2007 at the launching of a book on Mexico’s celebrated Piedras Bola located on a hilltop in a remote part of western Jalisco.

During the ceremony, I was seated in the audience, paging through my new copy of the book.

“I wonder what the altitude is in this picture,” I whispered to the man sitting next to me.

“1,925 meters!” replied the bearded stranger with such authority that I asked him how he knew that.

“Because I wrote that chapter you’re looking at,” he answered.

“What? If you’re an author, why are you sitting down here with us peons?” I asked, “Why aren’t you up there with the other authors?”

“Authors?” Cházaro whispered, “Those aren’t authors; they’re all VIPs.”

And I couldn’t fail to notice that those so-called VIPs never once asked those who actually contributed to the book to take a bow.

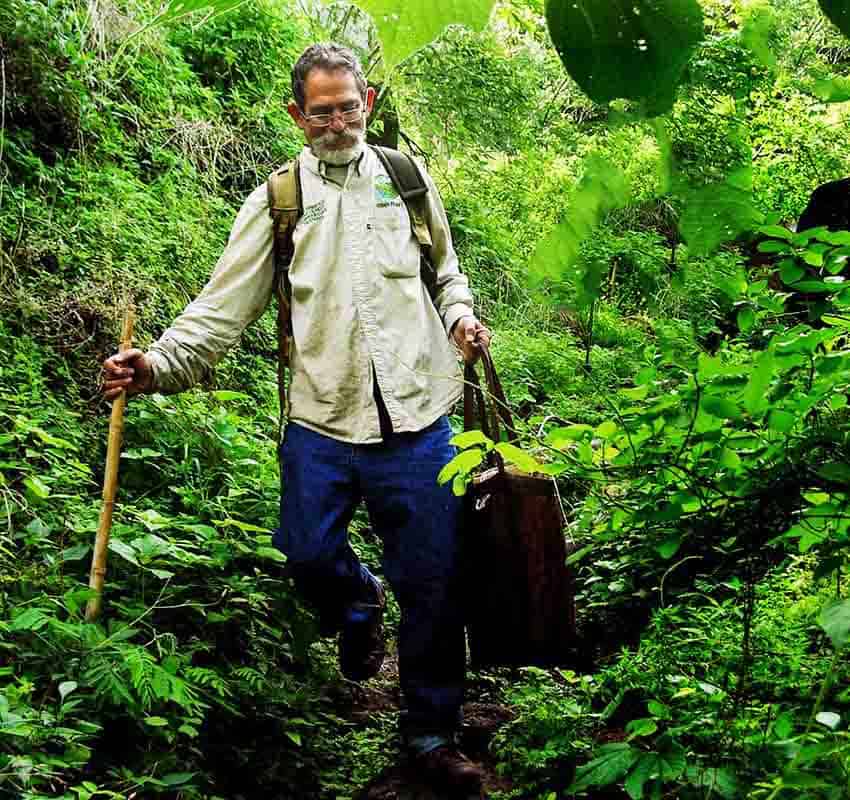

Cházaro’s accomplishments are all the more striking because they were carried out under the same hardships that affect most botanists and biologists in Mexico: low salaries and no funding for projects or equipment.

“Miguel made all those discoveries without a car of his own,” his friend (and frequent supplier of transportation) Roy Sánchez told me. “He simply couldn’t afford one. And I know for a fact that his university only allotted him 5,000 pesos a year for field trips — and not a centavo for expenses like gasoline.”

Cházaro, however, had a well-proven technique for finding transportation when he needed it. One day I received a call from him.

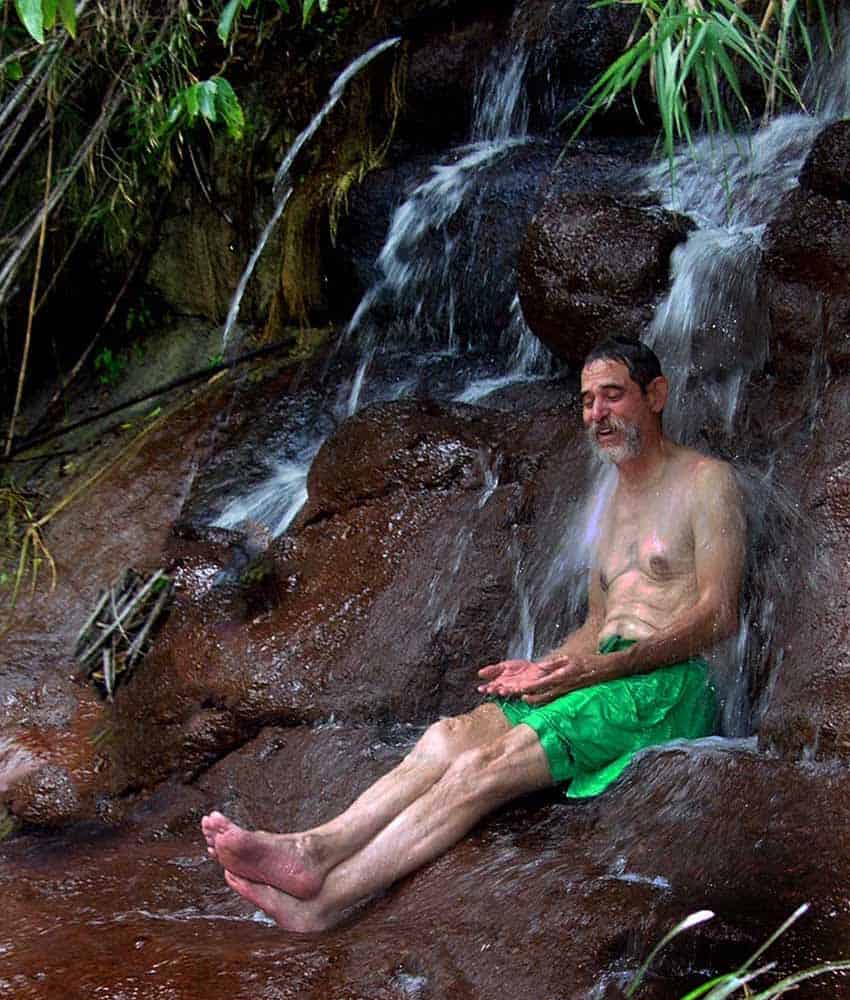

“John, I found a place you’ll love. It’s a delicious, natural hot waterfall located right next to an orchard where juicy mangoes drop right into your hands… and then there’s this unexplored pyramid…”

Of course, I was hooked and so were plenty of hiker friends who wanted to go.

“Miguel says it’s just outside town,” I told them.

Several hours after our departure for the hot waterfall, we found ourselves standing at the edge of a cliff overlooking part of the Río Verde Canyon, known as La Bolsa.

The waterfall really was there, but we had to hike 500 meters down to the bottom to enjoy it — giving Professor Cházaro plenty of opportunities to collect the rare plants that grew at different altitudes in the canyon.

Sánchez describes his first meeting with Cházaro as “both memorable and simpático.”

“The Natural Science Association had a field trip planned,” Sánchez told me, “and we were to meet in front of an ice-cream parlor. I was standing there talking with several members of the Association, when a man came walking towards us.

“This man was wearing a very dirty jacket, his hair was all disheveled and he was carrying what looked like a big shopping bag — a really tattered one, I must say. I figured he was some poor down-and-outer looking for a handout. Since we were all in the middle of a quite interesting conversation, I thought I would just give the poor guy some money so we could keep right on talking.

“Well, I was in the midst of pulling the money out of my pocket when everyone in the group shouted, ‘’¡Hola Miguel! ¿Qué tal, Miguel?’ all at once — and, fortunately, nobody noticed the money in my hand.”

Cházaro then explained to the group that he had arrived home that morning from a long camping trip of a week or so and that when he opened the door, his wife told him about this excursion.

“Oh, I can just make it!” he told her and turned right around and left.

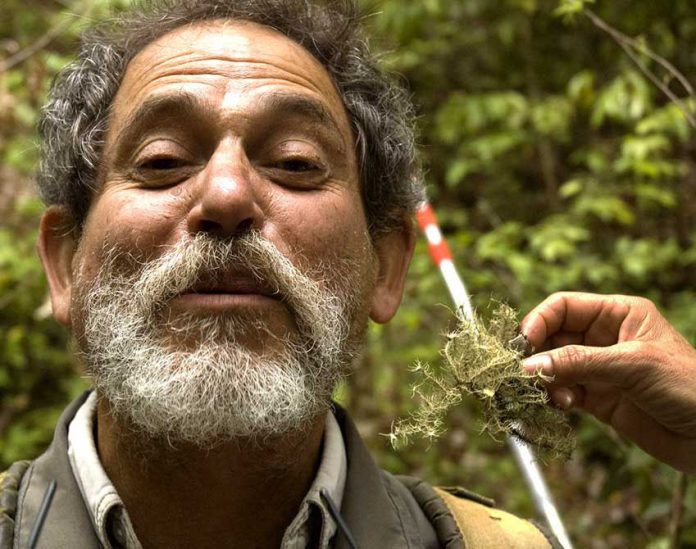

“So, you can see,” Sánchez told me, “he wasn’t a person preoccupied with appearances. And I should also mention that he never combed his hair, well almost never. ‘If you comb your hair, it’ll fall out,’ he used to say.”

As for Miguel Cházaro’s character, he was a person who loved to talk to people. If he came to a market, he would end up talking to everybody about the flowers or medicinal plants they were selling, asking them where they picked this or that herb.

As his colleague, forest engineer Raúl López, put it: “He was not just a great botanist — he was a great human being.”

Want to read more tales of the legendary Miguel Cházaro? Read our stories about the Mexican Maple Forest and the Amazing Singing Geyser.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.