Sitting at the edge of Mexico City’s border with México state, San Andrés Mixquíc was once a farming town, founded on one of the islands of Lake Chalco and surrounded by chinampa fields, where most of their crops were grown.

Today, this community has become a Day of the Dead holiday destination, and I’ve wanted to go since I heard about it years ago.

Each year, the city’s main cemetery is opened to the public and a display of burnt-orange Mexican marigolds, feathery-white flor de nube (baby’s breath) and thousands of lit candles decorate the tombs of the town’s departed in the main church, the Templo y Ex-Convento de San Andrés Apóstol de Míxquic.

Attending the festivities requires a real commitment.

You must be prepared to mix and mingle with a surge of humanity that even for longtime Mexico City dwellers like me can be intense. The scene is noisy: trick-or-treaters ringing handheld bells to call the souls of the dead back to earth; booming music flooding out from stands selling everything from cheap jewelry to grilled tacos; and the roar of crowds that fill Míxquic’s streets from midday on October 31 until the early morning hours of November 2.

The most intense element of this pilgrimage is, by far, inserting yourself into the Mexico City traffic and joining the thousands of inhabitants that cross the city from one side to another daily. From central neighborhoods like Roma, Condesa and the historic center (where most tourists stay when they visit the capital), the trip takes, at a minimum, two hours, if you are lucky. Not to mention that when you approach the entrance to Míxquic, there reaches a moment when being in a car is no longer advantageous and it’s easier to just get out and walk. You then amble up the main road toward the cemetery, swept along with the crowd.

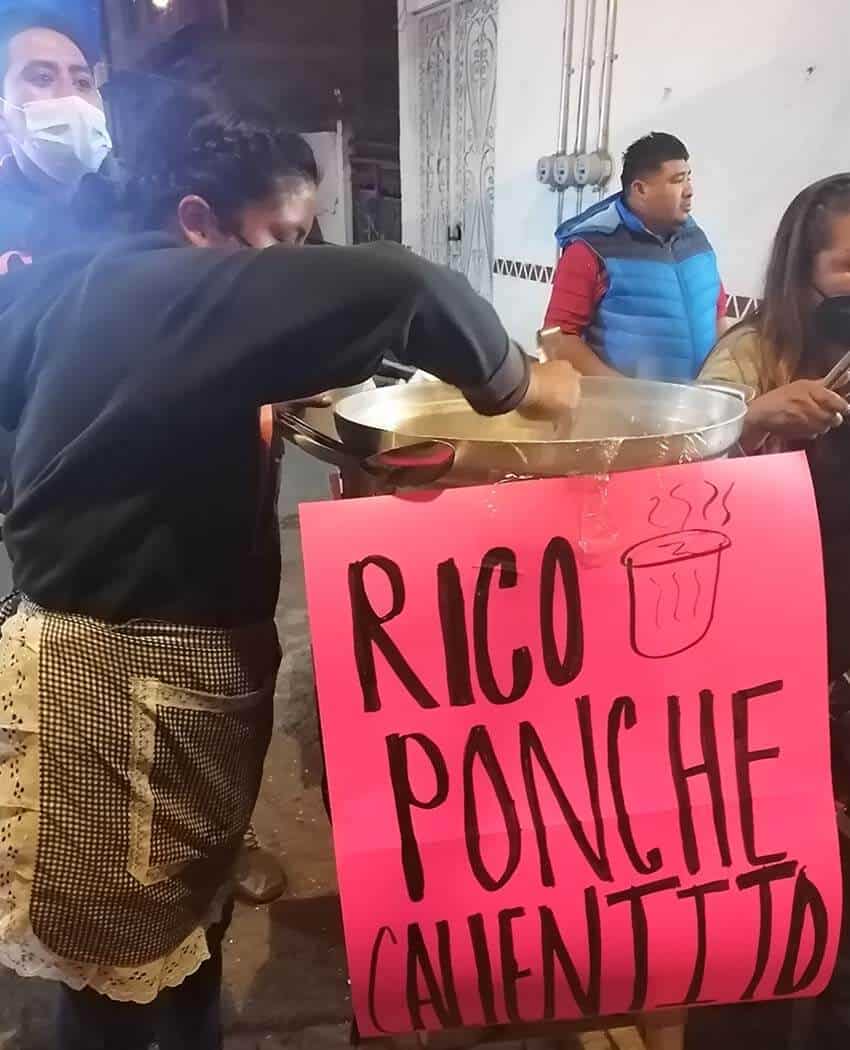

It’s best to get yourself a cup of ponche for the walk — a nonalcoholic version of mulled wine that takes the edge off the cold and makes the walk feel festive — then maybe a bag of sweet roasted almonds or sesame seeds from the stand announcing garrapiñadas calientes.

As you progress, the smell of roasted meat and sweet corn atole wafts from the street stands. The crowd urges you along, willing or not, until you are at the front steps of the church’s graveyard with its tombstones that sit cheek by jowl beside one another because, as one resident put it, “bodies just get piled atop one another over the generations” in the same small six-by-one-foot space.

The night to visit is November 2. If you go before, you will find all the same festivities, but the beauty of the graveyard isn’t revealed until that night, when local families come out in droves to decorate the gravestones of loved ones, light candles and commune with the dead.

“This year, unfortunately, my wife’s father died,” a local pan de muerto seller says, “and we are just waiting for him, you know? We put up his altar today on the table, and it’s as if he were here.”

While families commune with their dearly departed, tourists are welcomed to walk through the graveyard and get a peek at this centuries-old tradition. A walkway extends along one side of the cemetery’s wall and sits high enough that you can look down at the entire glowing landscape. It’s an overwhelming sight, the density of this cemetery making this nighttime celebration — called the alumbrada (illumination) — even more visually powerful.

People are looking forward to spending time with the souls of so many that were taken too soon by COVID-19. For many, it will be a first Day of the Dead without parents, siblings and grandparents. “We remember them every day,” says the bread seller, “but this day is completely dedicated to them. From the moment we wake up at home, we are making tamales; it’s a party.”

While meaningful and sacred, the fame of Míxquic and its subsequent flooding with visitors each year now means that this intimate local tradition is shared with multitudes. “It used to be much more traditional,” says another vendor selling vegetables and fruits outside the church’s walls. “It’s more vendors than anything else now. Truthfully, we have lost a lot of the tradition.”

But not all locals feel nostalgic for when Míxquic was just another anonymous country town. “For us, it’s a pleasure that [tourists] visit — for the business, for the economy of the town,” the pan de muerto seller says, “even more so now with the current situation. For us, it’s a plus.”

Breaking away from the crowd, along the side streets of the main thoroughfare, families set up altars in the garages and passageways that open onto the street. Most have a small basket out for visitors willing to toss in a few pesos for the pleasure of this glimpse at their private lives.

Altars are set up to honor loved ones with the four elements represented – earth, wind, fire and water — as well as a dish of salt for purification, a favorite food or a glass of tequila to nourish a spirit that has made the thirsty journey back to the living for this special night. As I walk, I see a guitar trio singing a slow ballad to the sepia-toned photo of a woman. In another home, the Lord’s Prayer is recited in front of a mountain of fruit and sugar skulls. A black-and-white photo of a couple perches at the top.

Handmade tissue paper lanterns in the shape of stars, boats and airplanes are delicately formed around light bulbs that serve as a beacon for the returning souls, some covered in plastic to keep off the rain that can dampen Day of the Dead festivities, which take place at the end of Mexico City’s rainy season. In the nearby town of Tecómitl, locals build small fires at the entrance to their homes that serve the same purpose.

The more mellow mood of Míxquic’s side streets is a taste of how many small towns in Mexico celebrate Day of the Dead: in the company of friends and family, with a ponche in one hand and a rosary in the other. As a visitor, I have always felt welcomed but never fully a part of the intimacy of celebrations. The sheer quantity of bodies in Míxquic can make moments of contemplation about the meaning of the season all the more difficult. Still, there is an understandable draw, especially for people who come from cultures where death is taboo and rekindling grief is something to be avoided.

If you can look beyond the crowds and mentally prepare yourself for the odyssey that is Mexico City traffic, Day of the Dead in Míxquic can be a festive glimpse at a tradition that most foreigners know little about. If you can’t, it’s better to stay at home and build your own small altar to honor someone you loved, cook their favorite meal and invite the people you love to share it with you.

Day of the Dead celebrations come in all forms. A visit to San Andrés Míxquic is just one of them.

Lydia Carey is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily.