In 1940, Mexican League baseball player James “Cool Papa” Bell had a season to remember.

Playing for the champion Azules of Veracruz, Bell became the first player in league history to achieve a feat called the Triple Crown — leading all players in three separate statistical categories: batting average, home runs and runs batted in (RBIs).

A few seasons earlier, Bell had come to Mexico as a highly successful player in his home country, the United States. Yet, his career there had been limited because of his race. Through an unofficial color barrier, the American major leagues banned Black players, who found an alternative in the Negro Leagues.

Many Negro League stars, including Bell, were described as being as good as, if not better than, their celebrated white major league counterparts. The Mexican League gave Bell and fellow Negro Leaguers a chance to play on integrated teams.

Bell’s narrative, including his years in Mexico, is receiving more attention through a new biography, The Bona Fide Legend of Cool Papa Bell: Speed, Grace, and the Negro Leagues, by Lonnie Wheeler. Poignantly, Wheeler died before the book was published, and some of the Black baseball stars he previously profiled have also passed away recently, including home-run king Hank Aaron.

March 7 marked the 30th anniversary of Bell’s death in 1991.

Bell was part of seven Negro League championship teams. Before coming to Mexico, he won a championship for the team of Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo. The 1940 Azules team featured six Negro Leaguers who would eventually be inducted into the United States National Baseball Hall of Fame — including Bell, who was inducted in 1974.

Bell has a cinematic link to another Mexican championship squad through the film The Perfect Game, a fictionalized portrayal of the 1957 Little League World Series champs from Monterrey; Bell was played by Oscar-winning actor Lou Gossett Jr.

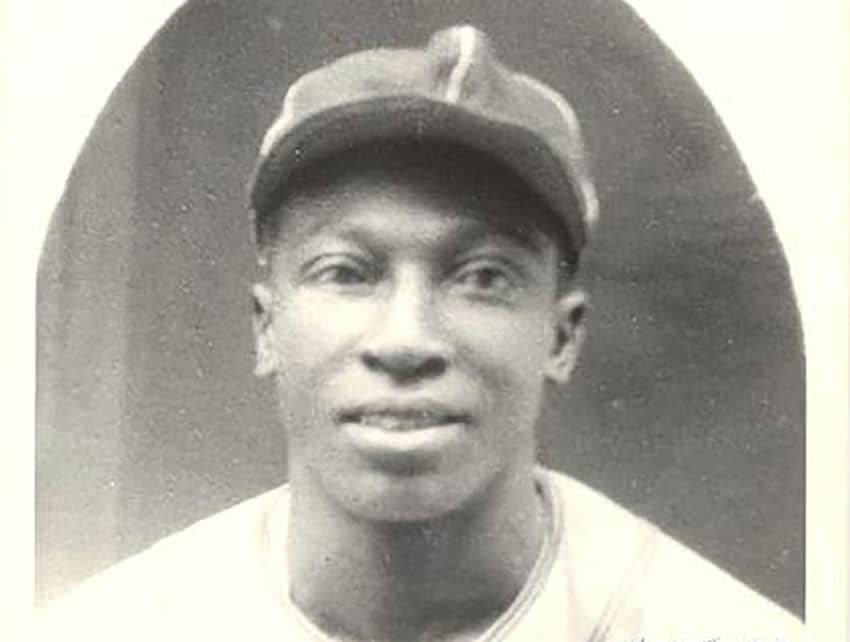

As for the real-life Bell, “His speed was legendary,” said Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. “He is still believed to be the fastest man to ever play the game.”

Kendrick cites an anecdote from another Negro Leaguer who played in Mexico, Hall of Famer Buck O’Neil. According to O’Neil, Bell’s speedrunning around the bases so stunned an opposing Mexican team that its players halted the game, convinced he had cheated.

His equally famous Negro League teammate, pitcher Leroy “Satchel” Paige, once reportedly witnessed his roommate Bell turning off their hotel room’s light switch and making it into bed before the light went out. Kendrick said this is a true story and attributed Bell’s achievement to both his speed and to a short circuit. “You’d flip the light switch off and there was a delay before it would go completely off,” Kendrick explained.

Ever after, Kendrick noted, “Satch would always say, ‘Cool is so fast. He can walk into a room, turn off the light, get in bed and pull up the covers before the room went dark.'”

Fans remembered his nickname as well as his speed.

“’Cool Papa’ is, I think, the greatest nickname in baseball players’ history, bar none,” Kendrick said. “It fit him. I tell people all the time, Cool was really cool. He was a snazzy dresser. He was so laid back. He never came to be rattled.”

The story of Bell in the Mexican League is rooted in its inclusionary approach toward Negro League stars. Over 150 players crossed the border south for better-paying jobs on integrated teams. The hospitality they received was similar to their experience playing elsewhere in Latin America, and much different from the U.S.

“Like a lot of players from the Negro Leagues who would go to Mexico and other Spanish-speaking countries, [Bell was] celebrated, treated with such great respect and dignity away from home,” Kendrick said. “I think Cool immensely enjoyed his time playing in Mexico.”

In contrast, Kendrick said, “the U.S. actually enforced racist laws — Jim Crow. It was not only a mindset, it was the law — separate restrooms, separate water fountains. There were places that did not even serve you, [where] you would not go in if you were Black.”

The book’s foreword describes how different the situation was in Mexico: in 1936, Bell and his Negro League team at the time, the Pittsburgh Crawfords, traveled to Mexico City to play a series against white Major League all-stars — something professionally prohibited in the U.S.

A year earlier, in 1935, Bell and the Crawfords won the championship. That squad is widely considered the greatest Negro League team ever. In Mexico City, future Hall of Famers were well represented among the Crawfords and their white opponents. Bell made an amazing defensive play against one of them, the great Rogers Hornsby, in the final game.

With the Negro Leagues rocked by the Great Depression, Bell began playing professionally in Latin America. First, he joined Paige and other Negro Leaguers in the Dominican Republic for a pressure-packed season on Trujillo’s team. Although the team won the championship, the newcomers feared the potential consequences if they lost, Kendrick said.

Mexico proved more welcoming when Bell followed Paige there in 1938 and began learning Spanish. With his first team, the Alijadores of Tampico, he could make as much as US $450 a month. That was five times what he made with his first Negro League team, the St. Louis Stars, according to Kendrick. The downside was the fact that railroad tracks ran through the Alijadores stadium.

Bell played two seasons for Tampico before becoming part of the powerhouse Azules, a new team, in 1940. Team owner Jorge Pasquel was also the head of the Mexican League.

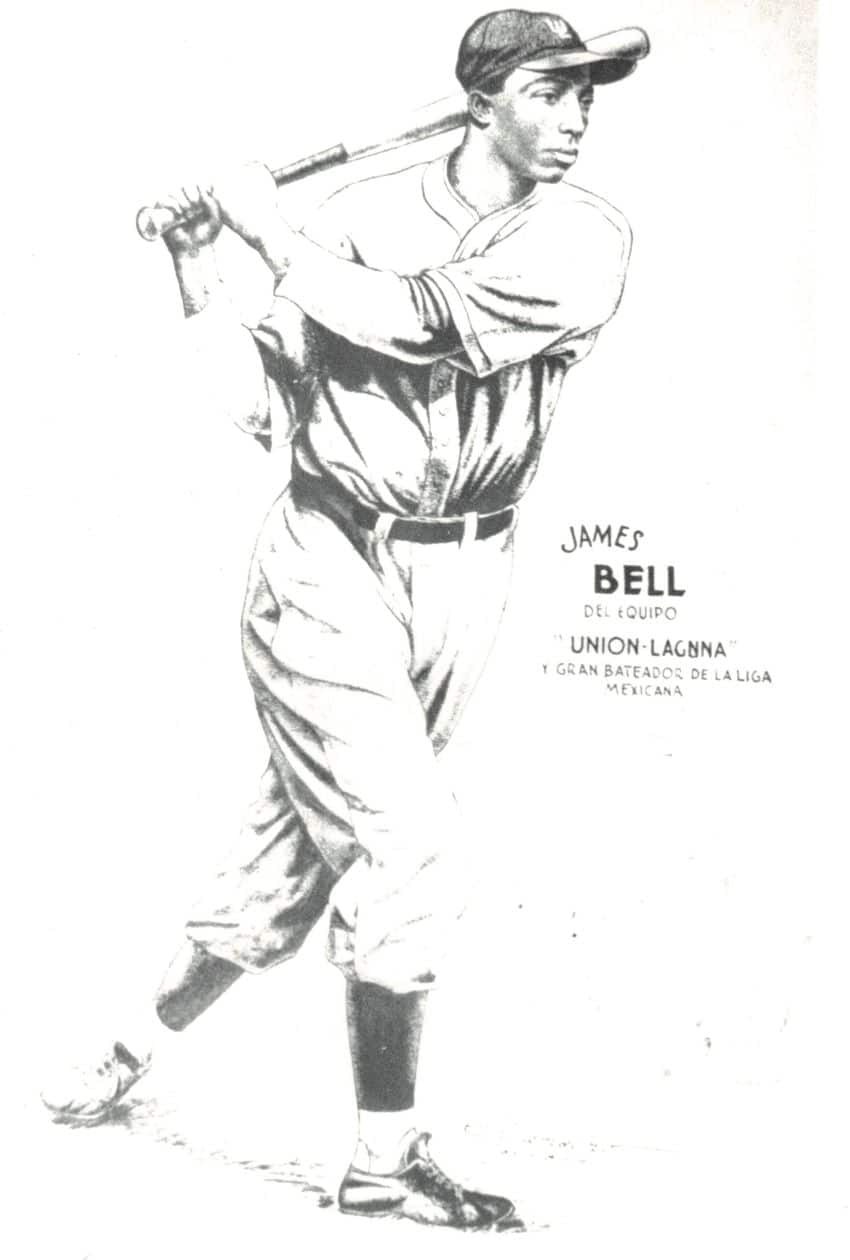

No matter where he played, Bell dominated. He won the Triple Crown in 1940 with a .437 batting average, 12 home runs and 79 RBIs. He also led the league in triples and runs scored. A Mexican postcard in his honor called him “The Great Batter of the Mexican League.”

“His years in the Mexican League, they mirror a lot of things he did in the U.S.,” said Leslie Heaphy, an associate professor of history at Kent State University at Stark and an expert in the Negro Leagues. “He was often in the top in the batting title, often in the top or near the top in stolen bases.”

Bell played one more season in Mexico for Monterrey in 1941. Heaphy attributed his return to the U.S. to several factors, including his increasing age; a desire to go home by both Bell and his wife, Clara Belle; and interest from a team in the U.S., the Chicago American Giants.

“Bell was often a sought-after player,” Heaphy said. “Many of the players came back after a few years. Even though Mexico, Cuba and the Dominican Republic were great places to play, they were not home in the same sense. Bell [followed] a similar path to many of the others who played for years down south and came back.”

The book describes the 1940s as a dramatic era for the Mexican League. Pasquel courted new talent while in New York, shopping with his wife, the famed actress María Félix; players were smuggled across the border in the trunks of cars, and the league sought to make inroads among white stars in the U.S. with varying success.

Kendrick sees Pasquel’s efforts to add American star power to the Mexican League as having increased pressure in the U.S. to integrate professional baseball.

“[The Mexican League was] not only signing Negro Leaguers,” Kendrick said. “You start to see [white] major leaguers coming into Mexico too. It’s very clear that Black and white players can play together … Now all the stars of the Negro Leagues and major leagues head down there. There’s the possibility of so much talent getting lost from major league baseball … There’s a lot of pressure on major league baseball and the commissioner to look at integration of the game.”

In 1947, the American major leagues ended their longstanding color ban when Jackie Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Bell gave Robinson some coaching to help prepare him for the historic opportunity, but Bell himself never played for an integrated team in the United States.

“The process of integration was so slow that age put him out,” Heaphy said. “In 1945, 1946, he’s pretty much at the end of playing in the Negro Leagues. Unfortunately, he’s in his 40s by that point. Sadly, because it took so long, he did not get the chance.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.