On March 9, 1916, the legendary Mexican revolutionary Francisco “Pancho” Villa launched an audacious attack on United States soil against the town of Columbus, New Mexico. In response, President Woodrow Wilson sent thousands of U.S. service members into Mexico headed by future World War I commander General John Pershing.

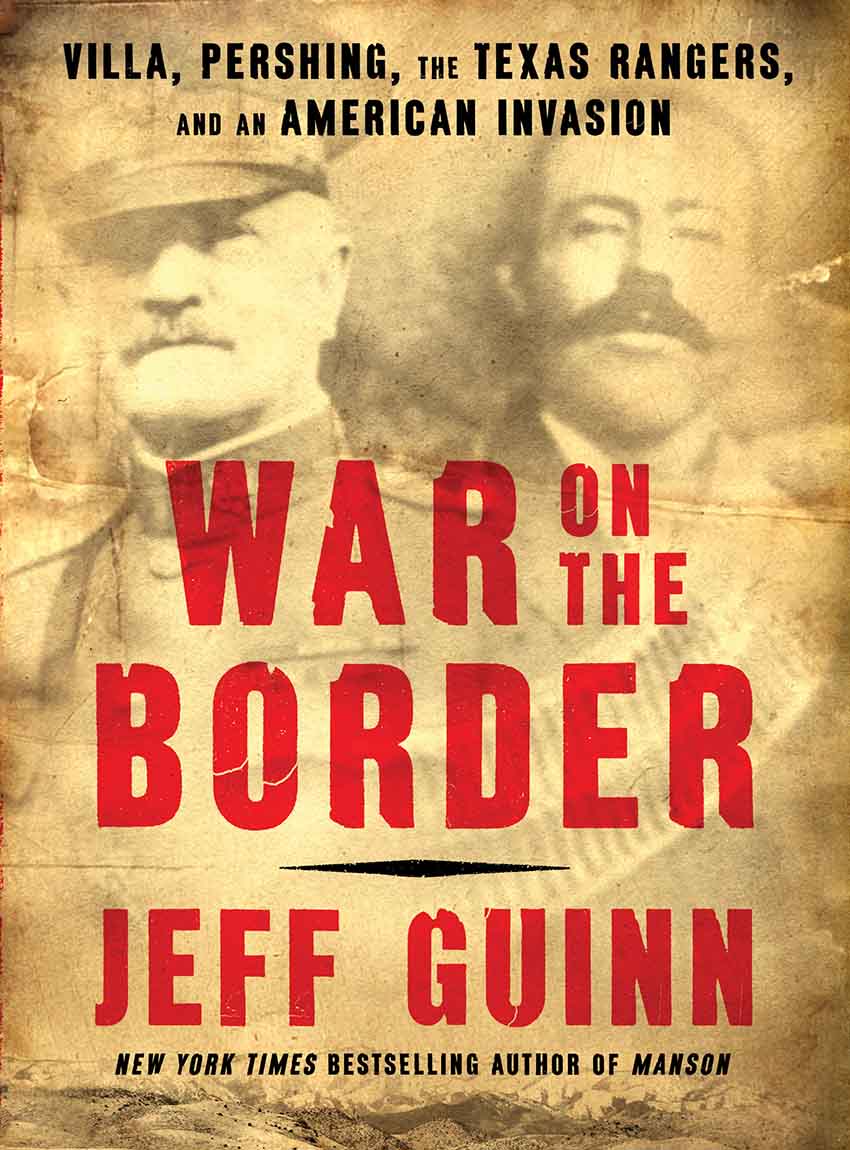

The U.S. military operation, officially called the Punitive Expedition, did not find Villa, but author Jeff Guinn found plenty of unanticipated similarities between that era and current Mexican-U.S. relations in his book, War on the Border: Villa, Pershing, the Texas Rangers, and an American Invasion, published earlier this year by Simon & Schuster.

“The same issues [in] the book exist today,” Guinn said. “There’s resentment on both sides. Beyond that, there’s the question of who should be allowed to cross the border and how that should happen.”

Guinn, who is based in Texas, was inspired in 2015 to write the book after hearing then-presidential candidate Donald Trump call for a “big, beautiful wall” along the border.

The more he researched, the more parallels he found between the present day and the time period.

Then, as now, the border was a place of simmering resentments. Sources of Mexican unhappiness stretched back to the 19th century with the Mexican-American War and the U.S. occupation of Veracruz in 1914 in reaction to a minor incident involving U.S. servicemen in Tampico, Tamaulipas.

In addition, American Texas Rangers had committed what Guinn described as a slaughter of innocent Mexicans during the Mexican-American War.

Americans, on the other hand, feared the Plan of San Diego — a Mexican attempt to send raiding parties against U.S. settlers, farmers and ranchers, a plan that derived its name from a municipality in Texas.

Guinn discovered that America had tried to build a border wall multiple times in the early 20th century without success. When he visited Columbus to watch commemorations of Villa’s raid, he noted lingering hostile sentiment among older Anglos and heard a disdainful comment about Mexicans that is quoted in the book.

“I did not want to finish the book on a depressing note,” Guinn said. “There could be change if people on both sides want [there] to be.”

Guinn did some outreach of his own. The historians he interviewed for the book included Mexican scholars Arnoldo de León and Miguel Levario.

“I also wanted to make sure I talked to some fine historians who didn’t have Anglo last names, who had other ideas and viewpoints,” Guinn said, calling de León and Levario “especially helpful.”

This is Guinn’s 21st book, with previous titles focusing on Americans who have grabbed headlines for varying reasons — from inventors Thomas Edison and Henry Ford to outlaws Bonnie and Clyde to the notorious Jim Jones and Charles Manson.

“All my books have a couple of underlying themes,” Guinn said, including “the difference between mythology and actual history.”

Iconic names populate much of his writing, and he noted that War on the Border features a “larger main cast of characters.”

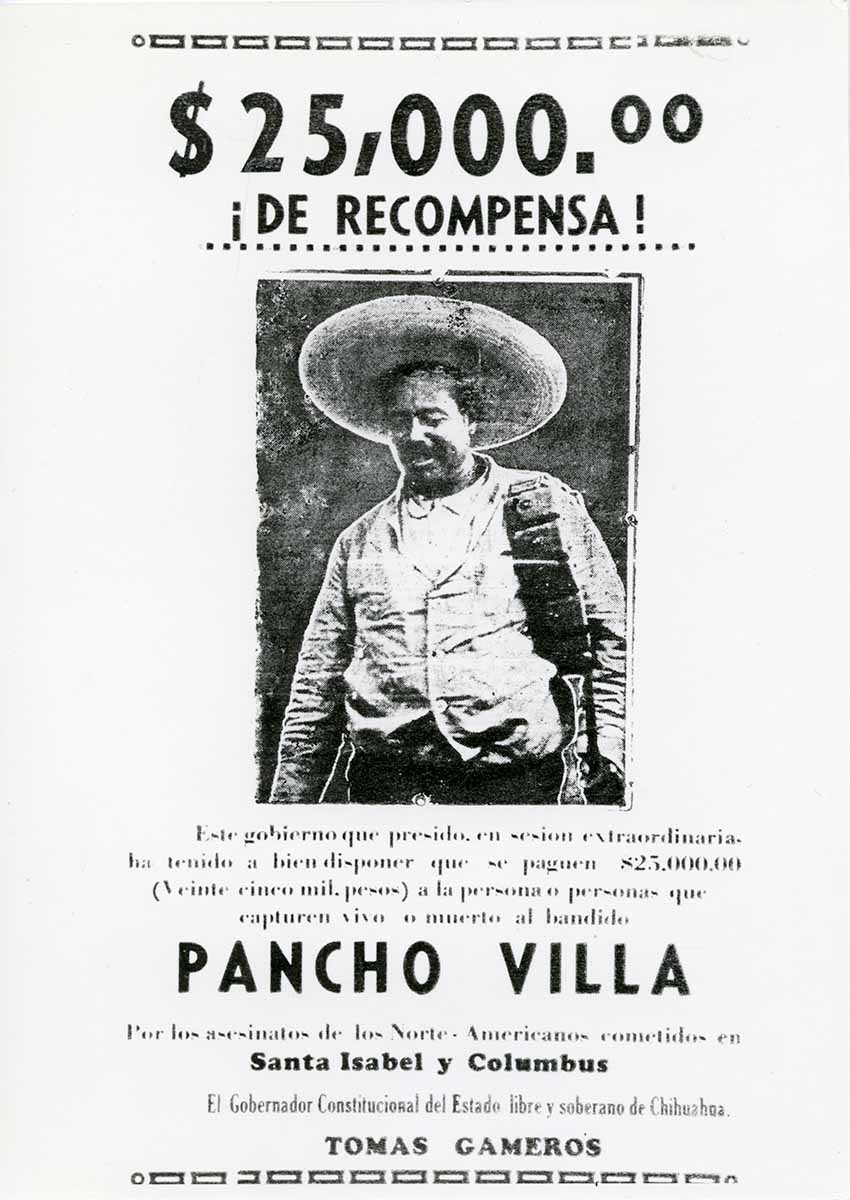

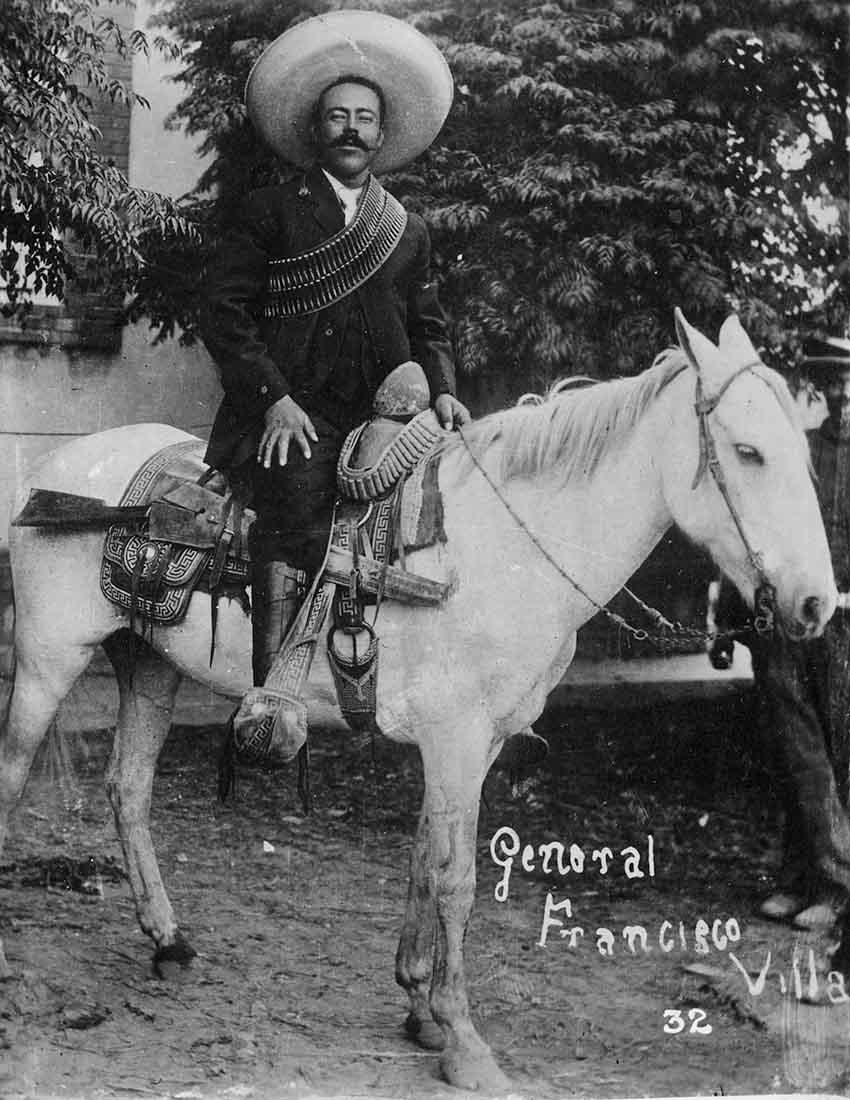

First and foremost, there was Villa, who was “obsessed with his public image, [who] wanted people to think he was invincible,” Guinn said.

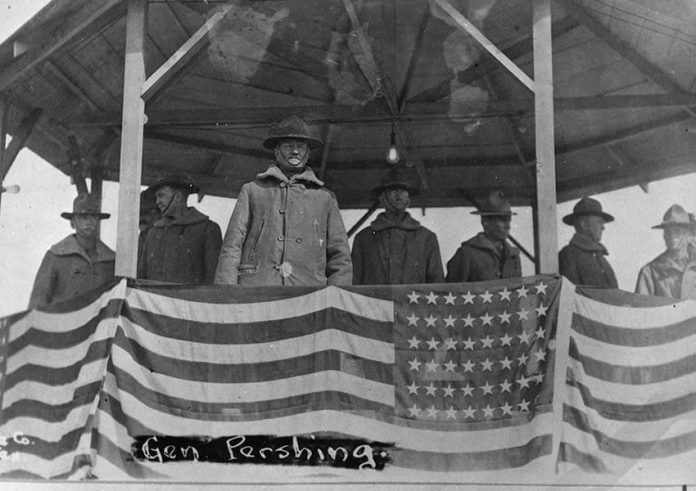

Other protagonists included Villa’s nemesis, the then-Mexican president Venustiano Carranza; future president Álvaro Obregón; and Villa’s fellow revolutionary, Emiliano Zapata. On the American side, there was Pershing, whose army included a promising young officer named George Patton.

In Washington, President Wilson monitored not only Pershing’s progress but his own reelection chances in the 1916 presidential campaign and the prospect of the U.S. being drawn into World War I.

It was Villa who drew the U.S. into Mexico.

As Guinn explains, Villa had seen himself as a friend to the U.S. but felt betrayed when Wilson recognized Carranza’s government in 1915. After Carranza’s military leader Obregón inflicted back-to-back defeats on Villa, the revolutionary’s cause plummeted.

To regain momentum, Villa devised a strategy: he would conduct a raid into the U.S. that would trigger an American invasion of his country. This would rally troops to his army, he believed.

“It was very well thought-out by Villa,” Guinn said. “It came close to succeeding.”

However, Villa’s spies underestimated the U.S. military presence in Columbus. Although the American commander was absent during the early-morning raid, civilians and military personnel showed on-the-spot leadership, with the U.S. Cavalry pursuing Villa out of town.

According to Guinn, 16 American civilians and soldiers died. Around 80 villistas did — more losses than Villa was expecting.

The Mexican commander did get his hoped-for invasion, however, a 4,800-strong force led by Pershing that featured a celebrated U.S. cavalry unit, a Black fighting force called the Buffalo Soldiers, who would participate in their final mission.

There were also several historic firsts: the Punitive Expedition sent by the U.S. used aircraft for the first time in reconnaissance, although this proved more of a liability than an asset. The U.S. military also mobilized cars and trucks, although it was another unexpected hindrance, given the rough terrain.

Pershing’s orders were to find Villa, not spark a wider conflict. Yet, the Mexican government, and most of the country’s citizens, would not help the invaders.

Two battles between American units and federales resulted in victories for Mexico.

“The American government begins to make up war plans for all-out war against Mexico,” Guinn said. “The Mexican government does the same.”

At one point, Villa was nearly undone by traitors from his own army; the attack badly injured him.

Yet, as loyal villistas carried their leader south, President Wilson ordered Pershing to withdraw into northern Mexico — allowing an arguably miraculous escape for Villa.

“Villa would love the fact that even all these years later, the term ‘miraculous’ is being used,” Guinn reflected.

After about a year, after Pershing’s forces had swelled at around 10,000, the Punitive Expedition left Mexico with Villa resurgent.

“Because there was so much resentment of the Americans, [Villa] did get many of the volunteers he was looking for,” Guinn noted. “In 1917, they were enough [for him to] reappear at the head of an even larger force.”

By then, wider geopolitics were in motion.

Wilson won reelection, and Carranza oversaw the passage of the Constitution of 1917. That year, Germany made its latest attempt to provoke conflict between the U.S. and Mexico to keep America from entering World War I.

Germany’s foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann sent a telegram to Carranza, urging Mexico to attack the U.S. to recover Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. The invitation ultimately came to the attention of the United States.

Not only did Carranza decline the offer, but it became a factor in American entry into World War I.

“I had no idea how long, in how many ways, Germany had been trying to make controversy between our two countries,” Guinn said. “I think it’s going to surprise an awful lot of readers.”

Guinn has learned much from writing the book. While it has led to a backlash among some of his readers, he’s hopeful others will learn from it.

“Any book these days dealing with facts that are not mythological or invented is going to be attacked by some people,” he said.

Yet, he added, “On the other hand, a lot of people are saying, ‘I did not know these things. I wish I had.’ Maybe it will change some minds.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.