In the early 1900s, the Amparo Mining Company operated one of Mexico’s most successful silver mines and was making money hand over fist.

Although it was located in remote hills 65 kilometers west of Guadalajara, rumors abound that a bustling community of some 6,000 souls once lived there, enjoying such luxuries as two supermarkets, a cinema, a dance hall and their own classical music orchestra. This community, it was said, consisted of Americans, British, Mexicans and lots of Germans.

All that is what the rumors say, but when I tried to dig up some hard facts about Amparo, I discovered a curiously different picture of life at the mining camp.

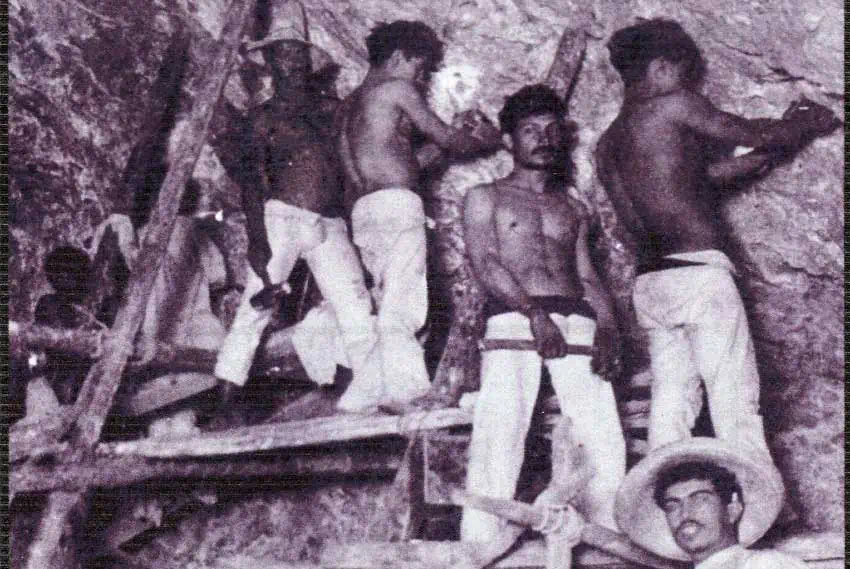

“The miners worked their long, miserable, heavy days under brutal conditions,” I read in a monograph by María de la Luz Correa. I got the distinct impression that the riches flowing from the mine had only flowed into the pockets of the owner who, it seems, was American, not British. I also found out that there were only about 500 miners at Amparo, not 6,000.

As for the two supermarkets, it was claimed that their primary function had been to enslave the miners, offering them luxuries and expensive entertainment on credit until they were hopelessly in debt.

The miners are long gone from the Amparo Mine, but an impressive ghost town still remains and it’s not a difficult place to visit. A short, 16-kilometer drive south out of modern-day Etzatlán, Jalisco, will bring you to the sleepy rancho of Amparo, surrounded by once elegant buildings now swathed in vines and bushes.

“This was the bachelors’ dormitory,” local people told me. “That was one of the stores, and this was where the miners received their wages.”

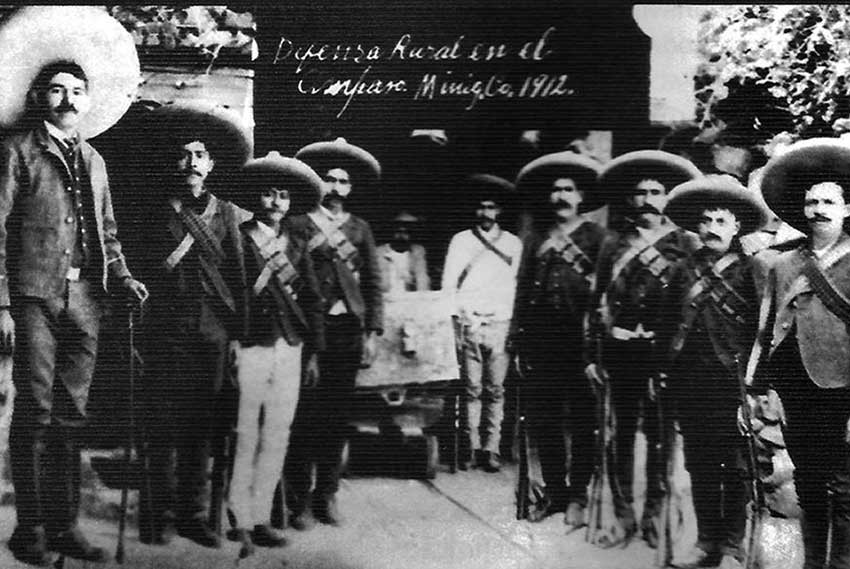

“What’s that, up there?” I asked, pointing to a lonely tower atop a steep hill. “We call that El Faro, the lighthouse,” I was told. “Actually, it was a watch tower built for driving away bandidos.” Once I saw the outside of this tower, pockmarked with bullets, I gained a new respect for those people who worked at this remote outpost, cinema or no cinema.

More of this mining operation’s ruins can be found about two kilometers south of Amparo at Las Jiménez, where electricity from high-tension wires was transformed into usable voltage for the mine’s heavy machinery. Here I found the most beautiful building of all, several stories high. I was told the transformers were housed here, but the building looks too elegant for such a lowly purpose.

One day a geologist brought me a treasure. Somehow he had managed to find a copy of the unpublished memoirs of Salvador Landeros, a mining engineer who grew up at Amparo and eventually became general manager of all its operations. Below are a few selected anecdotes that give us a feeling for what life was like in that remote mining town.

“I was born,” says Landeros, “in what was then called the Villa of Etzatlán in the state of Jalisco on the 31st of December of 1905. At the tender age of three months, I went to live in a remote place called Amparo where my mother had been hired to wet-nurse Fany, the newly born daughter of Mr. Santiago Howard, manager of the Amparo Mining Company. And that’s where I grew up.

“One of the people from my childhood I could never forget was a man with only one leg whom everybody called No Ambition (Poca Lucha). This man couldn’t work, but he had a special talent: he knew by heart all the stories of the Thousand and One Nights. We children all loved to get together with him at night to listen to his stories.

“Sometimes the grown-ups would come join us kids and everyone would give 10 or 15 centavos to our fascinating storyteller. And that’s how I passed my time before I reached school age, listening to those stories and playing. It was a peaceful time.”

The memoirs of engineer Landeros include quite a few stories of his own. Here is an example.

“When mining was at its peak at Amparo, we had an aerial tramway which transported the raw ore down to Las Jiménez in big containers suspended from steel cables strung among four towers. To avoid accidents, riding in the ore buckets was forbidden, but there were always a few characters willing to take a chance.

“Now, on various occasions, the electricity would go off, but usually for less than five minutes. If the men running the tramway were going to cut off the power for a longer time, they would send word up and down the system by telephone, warning people not to ride in the containers.

“Of course — even though it was prohibited — it was mighty convenient to get a ride uphill from Jiménez to Amparo and even people not working for the company used to take advantage. One of these outsiders was doing exactly that one day when the bucket he was riding in suddenly came to a halt 15 meters from the tallest tower. Now, by chance, there was a deep arroyo right at the foot of that tower, so the distance down to the ground was about 40 meters.

“Well, this fellow was sitting in the container, hanging in the air and he waited a long time and nothing happened. And he waited some more — and some more. And finally he just had to get down from that ore bucket and he looked at that distance, only 15 meters, and must have thought it would be easy to get to the tower just by holding on to the thick cable with his hands and walking along the thin cable below it with his feet.

“So he went for it and got about six meters when suddenly the power came back on and the containers started moving. Well, the very bucket he had been in came straight at him and cut his hands right off and he gave a shout which was heard by a passerby who saw him fall to his death.

“When they found his broken body at the bottom of the arroyo, they discovered he wasn’t even a miner. The poor guy was living all alone in Las Jiménez and no one had any idea where he had been going or why he had climbed into that container.”

El Amparo was one of very few Mexican mines that stayed open all through the revolution, and when it was over, there were 10 years of bonanza. The Howard management brought in good teachers for the school and the children got all the needed materials free. Football and basketball teams were organized and there were many fiestas and dances.

In spite of all this, the miners at Amparo, led by Mexican Marxist muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, joined a state-wide union in 1926 and made demands for better salaries and working conditions to the company, which chose to shut down the mine rather than capitulate.

This mine produced 138,597 kilograms of silver between 1924 and 1931, plus impressive quantities of gold, lead and copper.

It was still productive at the time it was shut down and would no doubt have been reopened later if President Echeverría had not (I was told) “stolen all the machinery and workings, causing the mine to be flooded.”

Why, with free football and dances, did the miners march off in protest to Mexico City behind leftist organizer Siqueiros? Some answers have been unearthed by local historian Carlos Enrique Parra Ron and you will find a few of them in The Dark Side of the Amparo Mine Story.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.

[soliloquy id="72393"]