Growing up in New Jersey in the 1970s meant that Mexico was almost like another planet, something that appeared in Clint Eastwood movies.

But since moving to Mexico, I have had two experiences that jarred memories related to Mexico from my primary school days — things I had read about in textbooks, then got a chance to find out they were really, really real. One was Teotihuacán. The other was the Paricutín volcano.

Paricutín did not become famous in the mid-20th century because of its size. It made it into the news and — decades later, into school textbooks — because it was the first cinder cone, or scoria, volcano to be documented in real time.

These are short-lived events geologically speaking, small volcanoes that suddenly emerge, erupt for a time, then go completely dormant.

Paricutín arose from Michoacán farmer Dionisio Pulido’s cornfield in 1943; its eruption officially lasted for nine years. By 1952, it had left a 424-meter-high cone, two towns completely buried in lava and ash and three others heavily damaged. Hundreds had to permanently relocate, resulting in the creation of two new towns.

Since then, however, the volcano has become something of a blessing, bringing tourists to see the cone, which “smolders” because of water getting into the still-hot cone, and the partly buried church of San Juan Parangaricutiro.

It is worth the visit to get a taste of just how little Mother Nature cares for humans when she decides what she’s going to do.

For weeks before the eruption, locals reported sounds like thunder but no clouds, probably from the movement of magma. There were also hundreds of small earthquakes the day before the eruption started.

The spot where the crater arose in Pulido’s field had always been low, and corn did not grow well there. At the time of the eruption, he and his family were working that field.

Suddenly that spot swelled and formed a fissure more than two meters across, hissing and ejecting hydrogen sulfide. Within hours, the fissure was a small crater.

The entire town was alarmed as the volcano grew. Celedonio Gutiérrez, who witnessed the eruption on the first night, reported, “… when night began to fall, we heard noises like the surge of the sea, and red flames of fire rose into the darkened sky — some rising 800 meters or more into the air —that burst like golden marigolds, and a rain like fireworks fell to the ground.”

Spewing ash, smoke and rock, the volcano reached 50 meters in height on the first day, and 100–150 meters by the end of the week. Within eight months, the cone was 365 meters tall, forcing a series of evacuations that extended outward as the volcano grew. Fortunately, the lava’s slow movement meant minimal loss of life.

Most of the growth and damage occurred in that first year, but it brought many journalists and scientists from Mexico and abroad to study the development of a volcano. Tourists also came to see the spectacle despite the danger of unseen flying rocks.

From then on, activity slowed and interest waned, leaving mostly a few scientists to see Paricutín’s last major burst of activity in early 1952.

The volcano captured the imagination of many in the mid-20th century. It made international news despite World War II. There are references to it in Hollywood movies from the time as well as in artworks such as those done by Diego Rivera and Dr. Atl.

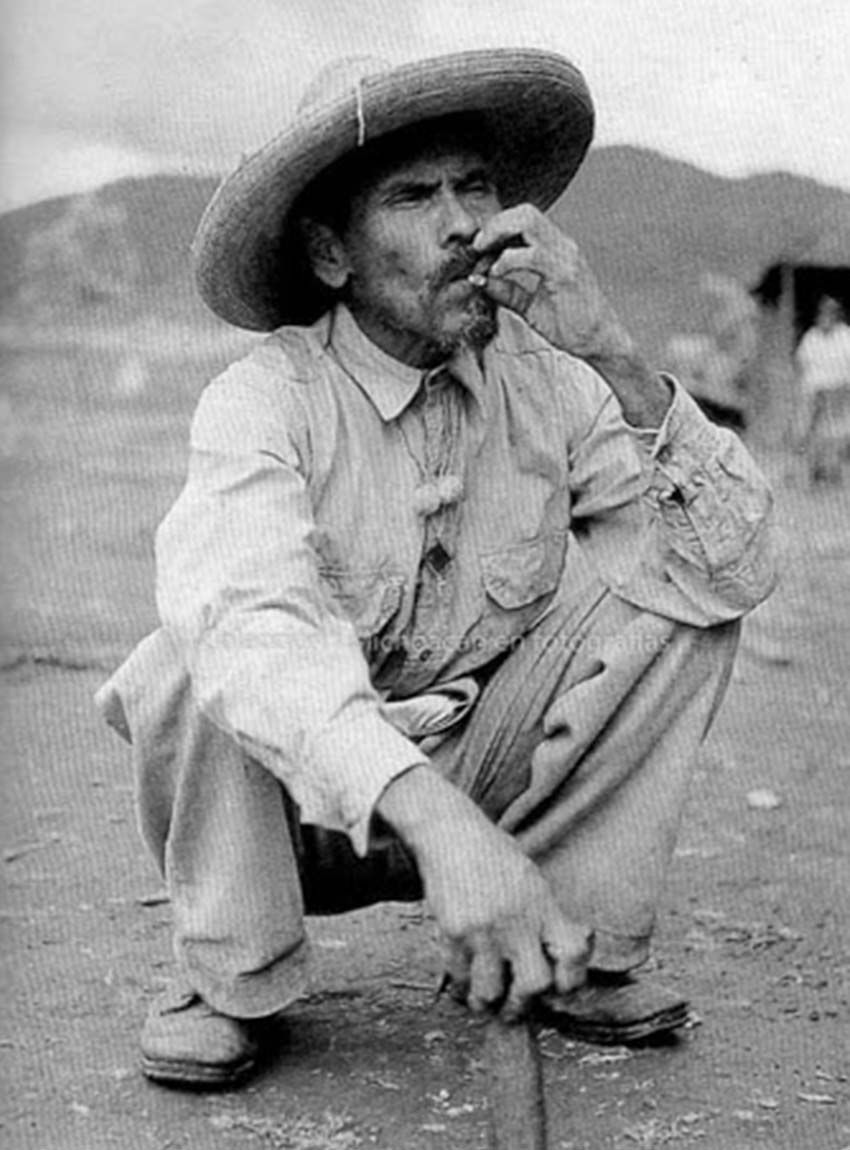

Needless to say, it was a disaster for the residents of Paricutín and Parangaricutiro. Both towns were completely encased in lava. It destroyed the lives of local residents, not in the least that of Dionisio Pulido, who did not lose his sense of humor despite everything.

Before leaving his home for the last time, he placed a sign on the cornfield that read in Spanish: “This volcano is owned and operated by Dionisio Pulido.”

But since then, there has been a silver lining: the dramatic almost buried church alongside the still-treeless cone has brought tourists to the area ever since. Writer and tour organizer Tony Burton says that many people “of a certain age” come to Paricutín specifically because they read about it as a child.

Both the volcano and lava field over the church are accessible by foot or horseback and make for a very good initial introduction to the area’s natural beauty and local Purépecha culture. Climbing the volcano requires a guide, but the buried church doesn’t. While the attractions do bring in a significant number of tourists, the attraction has not significantly ruined the traditional way of life in the area.

The Purépecha community of Angahuan, about 32 kilometers from Uruapan, is the gateway to the volcano and lava field. Locals still weave rebozo shawls the way they always have, and food is still often cooked over wood fires, especially in homes and small family restaurants.

The town provides cabins and other accommodations with stunning views of the volcano, as well as a museum dedicated to it. The town and the volcano can be visited year-round, with comfortable temperatures in the daytime, although it can get chilly at night.

Paricutín has been called the youngest volcano in the world, but that is debatable. This particular volcano may never erupt again, but there will be another at some point in the future somewhere in Mexico.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.