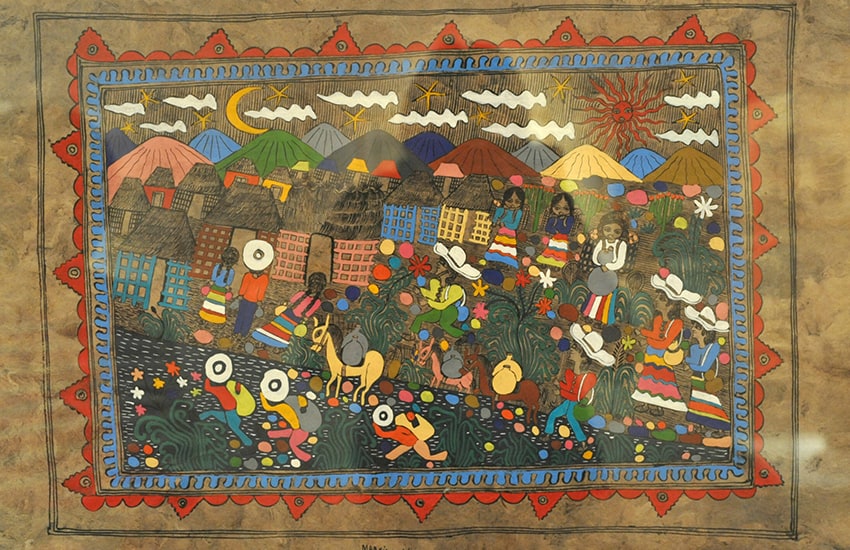

Most visitors to Mexico have likely seen the popular and affordable Mexican souvenir of bright paintings on a dark-brown, rustic paper. These look like something that has been done for centuries, but in reality they are the result of a recent merger of two separate indigenous handcraft traditions.

The bright painting is done by the Nahua peoples, who inhabit the Balsas River area in the state of Guerrero. Originally, these images were used to decorate traditional pottery, but they were transferred to the new paper medium.

Meanwhile, the paper is made by an Otomí population centered in the tiny village of San Pablito, part of the Pahuatlan municipality in the Sierra Norte mountains of Puebla.

Both peoples live in highly isolated areas that have managed to keep many of their traditions. So how did the two even find out about each other’s work?

Tourism may drive most of the demand for handcrafts today, but their importance in Mexico arose after the Revolution as part of a national identity (mexicanidad) promoted by the government. This created a market for handcrafts in Mexico City, which just happens to be between the territories of the two communities.

Essentially, each learned about the other at the market.

Sometime before the 1970s, someone got the brilliant idea of painting the Nahua pottery designs onto the Otomí paper.

For the Nahua, this has a number of important advantages: the painted motifs account for most of the pottery’s value. A flat surface is easier and quicker to paint on. Perhaps most importantly, paper is much easier to transport to market and easier for buyers to take home.

The Nahuas’ interest in the paper was that it gave the paintings a historical and traditional look, something that is extremely important in handcrafts and indigenous products. For the Otomí, their Nahua buyers provided something they needed, bulk purchasers that made commercial paper production economically viable.

Sounds like a win all around … but not quite.

Producing the paintings and the paper that they are on has become economically crucial for both groups, even vital. Because of cost, the paintings themselves are done with commercial acrylics, which pushed out traditional paints and pigments long ago.

But the real issue comes with the paper, called amate.

In the pre-Hispanic period, it was extremely important, not only for documentation but also for religious ceremonies. This religious importance led the Spanish to abolish its making, with only a few, highly isolated communities such as the Otomí in the Sierra Norte able to continue making and using it in secret.

This preserved the technique of taking the inner bark from various types of ficus family trees and pounding them together to make sheets. Unfortunately, the commercialization of these sheets has decimated the trees that produce the bark.

The ficuses that produced the lightest and most prized paper were wiped out about 40 years ago, followed by just about the rest of the family of trees, according to handcraft expert and author Marta Turok. Any naturally light amate paper made today from ficus is from bark brought from Central America.

As tropical ficus trees in that part of the world grow slowly and with some difficulty, most of the bark used today comes instead from an entirely different species, Trema micrantha (locally called jonote). It accounts for about 80% of the bark pounded in San Pablito.

This tree grows fast and has a wide range, from Florida to Argentina. In Mexico, it grows in poor soils and is prevalent in the east of the country. It is often used as a shade tree on coffee plantations in Puebla. In fact, most of the harvested bark is from such coffee plantations.

Paper makers used to get this jonote bark themselves from the surrounding area, but at this point in time, the local ecosystem has long been stripped. Instead, amate paper makers rely on jonoteros, who have to bring bark to this isolated Otomí mountainside village from ever farther away.

There is some interest in cultivating jonotes for their bark, but this requires some training. There is also concern that growers would put in the two to five years needed for harvestable trees only to have the bark stolen.

There is one other problem with the jonote bark: it is tougher than ficus bark and requires caustic soda to soften it and chlorine to lighten it. (Worse chemical dyes are used to create all kinds of colored paper.) The use of these substances has caused serious problems in the small valley’s watershed.

Ecologically, the easy answer would be for the Nahuas or someone else to find a substitute for the amate paper that would give the “timeless” look that bark paper does. But then this would pull the rug out from under the Otomís’ only source of outside income. It may happen anyway sooner or later, as the difficulties of producing the paper drive up prices beyond what the Nahua can pay.

The tough question for outsiders is “Should I buy the amate paper paintings?” There is no easy answer.

Perhaps the least benign market is the largest one — the market for making blank sheets — as it uses up the most resources with the least economic benefit for the Otomí. There has been some shift in San Pablito to making amate paper decorative works, usually with light-dark contrast. This still means the use of chemicals, but the result is a finished product that brings in more money.

Several universities and others are still trying to find ways to make the paper production more economically and ecologically viable. As for the Nahua, they still make pottery, much of which is quite exquisite but less profitable.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.