The workshop where blocks of marble and onyx are turned into figures, bowls and lamps is layered with dust. Toward the back, Francisco Camargo carefully guides a saw as it cuts through the edge of a piece of marble he’s been shaping into a bowl.

The saw whines as it spins at 3,700 revolutions per minute. Water pouring down from the saw onto the marble keeps it cool and prevents it from cracking. On the floor around him, water has mixed with the dust to form a slurry. Despite the mess, Álvaro Meza Hernández — Camargo’s boss and the owner of Mezher, a store specializing in all things made from marble and onyx — is happy.

“I like to come here and work still,” he said. “One day, two days. I love it.”

Tecali de Herrera, the pueblo where Mezher and dozens of other stores sell items made from marble and onyx, is about 30 miles southeast of Puebla. The word tecali is from Náhuatl, usually translated as “house of stone.” The pueblo was first settled in the 12th century by the indigenous Chichimecas and became known back then for its marble and onyx figures. Their work was so prized that they had to send pieces as tribute to Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Aztec empire.

According to a plaque in front of the zócalo, Franciscan friars arrived in 1540 and built the pueblo’s first convent. A second convent — whose construction was begun in 1569, according to the Mexican government — was built on top of the first, and the ruins of that one still stand. Although it’s one of the pueblo’s main tourist attractions, it’s been closed due to the pandemic. It can still be seen from a distance, although the view is through a fence.

Mezher was founded by Meza’s father. With two locations, it is one of the largest retailers in Tecali.

“I started working here 50 years ago,” said Meza. His children are the third generation to learn the craft of shaping marble and onyx. “It is complicated to learn,” he said. “It depends on a person’s ability. Out of 10,000 people, maybe 20 have the ability to do good work. Fortunately, the family has this ability.”

Anyone interested in working with marble and onyx must first learn how to polish and sand the stones and then how to clean them with muriatic acid. “One needs to make perfect movements to polish,” said Meza. “All of the work must be detailed.”

With time and practice, if they’re one of the few with talent for this kind of work, a person moves on to making small pieces.

“It takes at least four years of training to start making pieces of medium quality,” Meza said. “It takes at least 10 years to make a good artisan. To make a fine sculpture takes 15 years of training. To become a master, one needs good hands and a good mind and, more than anything, creativity.”

The bowl that Camargo is working on started out as a block of onyx.

“One needs to know the stone beforehand because there are many imperfections,” he explained.

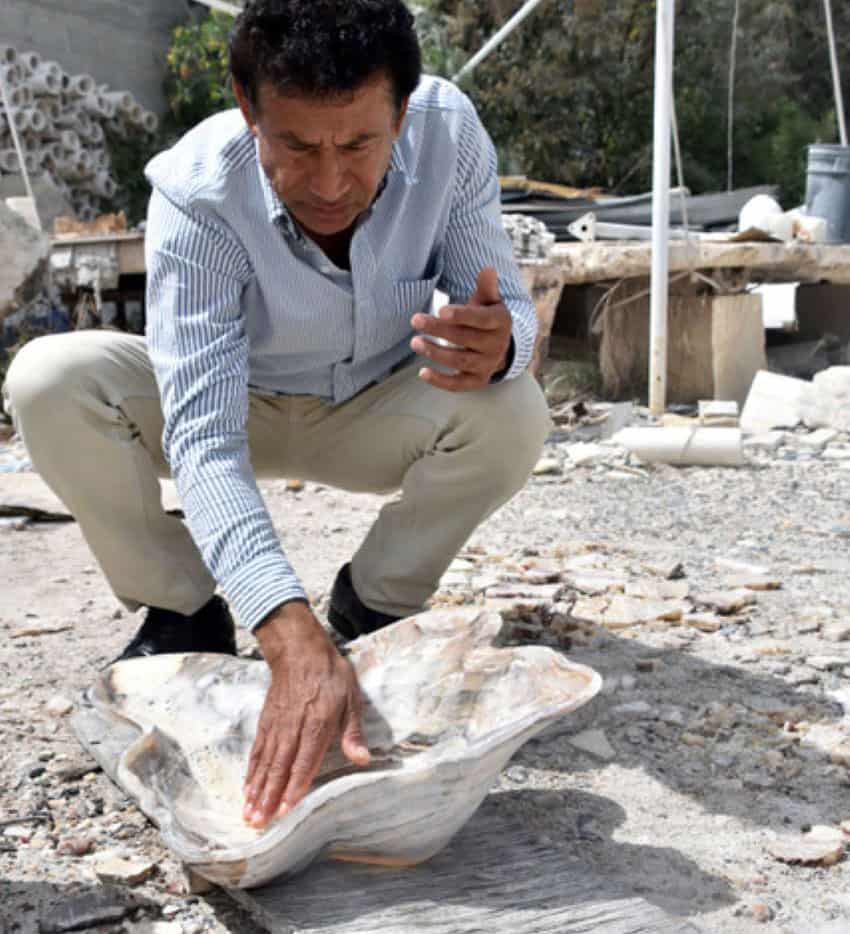

When Camargo, who has worked for Meza for a decade, spots an imperfection, he marks it and then fills it in with epoxy to strengthen the stone. Although the imperfections, when pointed out, are clear, it takes years of training to tell a stone’s quality. “I can tell a good or bad rock with touch,” said Meza, “not with the eyes.”

When the stone is judged to be of high enough quality and the imperfections are adequately prepared, Camargo uses the saw to make the initial cuts and then chips out the thin pieces with a hammer and chisel. “The strokes are made as the craftsman creates something artistically,” Meza said. “He will make deep and gentle cuts, adding creative touches.”

Close attention must be paid when using the saw because the piece can be quickly pulled forward, cutting a person’s arm or hand. “It is very dangerous at first.”

A fine white powder covers the finished pieces, and this is removed by washing them with muriatic acid, a step which brings out the stone’s colors. Meza washed a bowl without using gloves. “It does not hurt,” he assured me.

The acid bubbles as it works, and when it stops bubbling, the bowl is dipped into water. After several washings, it had a lustrous shine.

In addition to the workshop where smaller items are made, Meza has another much larger workshop where huge blocks of marble and onyx — some weighing as much as 30 tonnes — are turned into tables and counters. His is the only shop in Tecali that can cut blocks that large, and he often cuts them for other stores in the pueblo. Tables and countertops are made by first cutting the blocks into slabs using very large, frightening-looking saws. Slabs are then cut to size by another smaller but still frightening-looking saw, then polished to bring out the colors.

Meza’s store sells mostly small to medium-sized figures, but anyone interested in finding a figure large enough to place on a front lawn will find plenty of options along the main road in Tecali. The front of Armando Contreras’s workshop is filled with figures that measure three or four feet. There are figures of the Virgin of Guadalupe, a Buddha or two and a striking rendition of an iguana.

“That took two weeks to make,” said Contreras, “and at least six to eight years to learn how to make it.”

Mezher and other stores in Tecali sell all sorts of items made from marble and onyx. “There are different types … that are used for sculptures and for decorative figures,” Meza said. The onyx used in Tecali is sometimes referred to as Mexican onyx and can be distinguished from marble by the beautiful bands of color that run through it.

“The colors come from sediments, water, minerals and contaminants,” he said. “Where there are no contaminants, there are no colors, and light can pass through. Onyx is used for lamps because it is translucent.”

For the uninitiated, it can still be difficult at times to tell marble and onyx apart. “I can tell … because of my experience,” Meza said. “Onyx is more crystalline.”

He paused a moment while he searched for other words.

“It is really impossible to explain.”

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer and photographer, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.