I have been describing interesting trails in western Mexico for around 35 years.

The very first I wrote about was the long, steep sendero leading to Las Piedras Bola, Jalisco’s Great Stone Balls, a site so unusual and curious that it actually made the cover of National Geographic back in August of 1969.

The hike to the Piedras was memorable because our guide, a 10-year-old boy, managed to get us lost just long enough for the first feelings of panic to tingle the hairs on the back of my neck.

I decided then and there it was my sacred duty to make my routes so obvious that my readers would be able to reach their destination entirely on their own.

For years I drew trail maps (with lots of landmarks) to show the way until at last, handheld GPS units came along, making it a whole lot easier to record and follow trails, step by step.

Now I’m happy to report another milestone for hiking in Mexico: the (Spanish-only) web page of Senderos de México, an organization dedicated not only to helping people find their way along Mexico’s vast network of rural trails, but also to rescuing, rehabilitating and preserving ancient footpaths, some of them in use before the arrival of the conquistadores.

“The problem,” says Javier Michel Menchaca, one of the organization’s founders, “is that mechanization is reaching remote communities and many of our nation’s great old trails are simply vanishing.”

This realization prompted the founding of Senderos de México five years ago and the rehabilitation and sign-posting of numerous trails, 10 of which are listed on their website.

As for standardizing trail information, they have consulted with similar organizations in the United States and Spain to create a national system that will make it easy for people to understand distance, difficulty and direction of a trail as well as the attractions hikers might see along the route.

The trail-marking system they have chosen is the Grande Randonnée (GR) code used in France, Spain, Portugal and the Netherlands. This extremely simple system consists of two parallel bars of color to show you’re on the right trail. These are painted on trees and rocks with “eco-friendly” paint.

Right-angle versions of the bars indicate a left or right turn. If you should see the two bars crossed, however, it means you’ve wandered off the right path and you’d better backtrack. Here in Mexico, Senderos is using white and red bars for long trails and white and yellow for short ones.

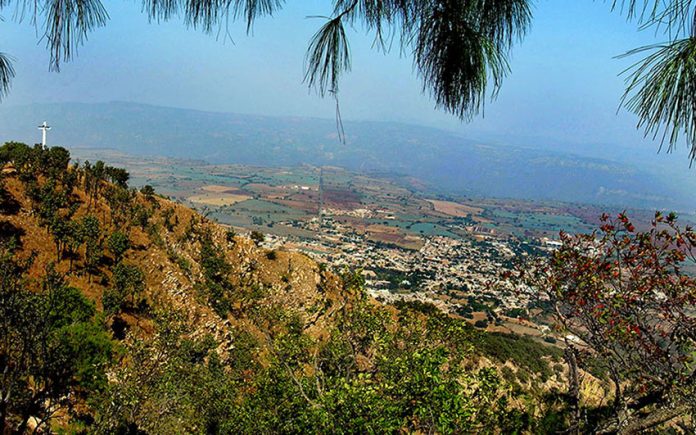

I decided to test the efficacy of this system by visiting a site recently signposted by Senderos. This is a steep hill called El Cerro de Amatitán, located 32 kilometers northwest of Guadalajara. Its peak is 1,793 meters (just over a mile) high and the cerro is famed for its beautiful vistas.

I had my eye on two Senderos trails up to the top of the mountain, one from the north and the other from the south.

“This,” I told my hiking partners, “will be a real test of the trail signs. We’ll go up the mountain one way and come down the other and if we survive, it means the system really works.”

We headed for the town of Amatitán, parked where the trail called “El Sendero del Agave” begins and, voilá, immediately spotted yellow and white stripes painted on a small rock. This sendero takes you through fields of blue-green agaves around to the south side of the mountain and then leads you to the top.

Our path was actually an old road — older than we could imagine, in fact. Alongside it we soon came to a plaque explaining that we were walking along what used to be called El Camino Real, once upon a time the royal road leading from Guadalajara to the port of San Blas, and paved with stone “Roman style.”

After a rather long meandering walk along wide dirt roads through agave fields, we reached the base of the Cerro de Amatitán and there the ubiquitous and handy trail markers suddenly ended.

Unfortunately, exactly at that point heavy maleza (brush), stone walls and barbed wire were sealing off our access to the mountain. Try as we might, we could not find a convenient connection between the road we had been following and the trail heading up the mountainside.

“Senderos de México forgot to tell us we’d need a machete,” I cried to my compañeros as I battled through the two-meter-high brush — sprinkled with an abundance of thorn bushes, I might add.

At last I clambered over the formidable combination stone wall and barbed wire fence, only to find my friend Rodrigo Orozco munching an apple next to a thick tree — with white and yellow stripes on it.

“Yippee!” I shouted, “we’re back on the trail!”

Well, back on the trail only in a manner of speaking. You see, that lovely trail lasted only 10 minutes and did not appear again until we reached the very peak of the mountain. Fortunately, the signs continued guiding us, painted on rocks and trees.

“I now have a new understanding of the word sendero,” I told my fellow hikers. “It means ‘way’ in the vaguest possible sense, which may or may not include a path.”

Well, bushwhacking our “way” up Cerro Amatitán was doable, but slow because the difference in altitude from the bottom to the top was 519 meters.

Sweating profusely, we finally reached the very pinnacle of the mountain, which offers a splendid view in every direction.

In a few minutes we arrived at a huge cross, the object of a yearly pilgrimage which, I told my compañeros, “is made by just about everybody in Amatitán, including great-grandmothers and 5-year-olds.”

With this consoling thought, we headed down the northern side of the hill, still guided by the white and yellow trail markers — only this time there really was a trail!

The views on the north side were much more stunning than those we had seen on the way up, but we dared not gaze upon them while walking because that trail I was so delighted to be on just happens to be strewn with billions of small, nearly round stones.

Yes, hiking on the north side was like dancing on ball bearings, and we had to watch our every step.

[soliloquy id="93182"]

Once again the Senderos markers guided us all the way down to the base of the mountain and then, alas, once again seemed to disappear. “So how do we get into Amatitán?” we asked ourselves when we ended up facing a high wall.

We began scouting around and soon Rodrigo shouted: “I found a gate in the wall, let’s go this way!”

Well, Rodrigo’s gate turned out to be locked and guarded by a whole lot of cows as well as a sea of thick, black — well, let’s call it mud. Now thoroughly pooped out (in every sense of the word), we dragged our tired bodies through the “mud,” climbed over the fence, slogged through even more goo on the other side and came to yet another stone wall, this one even higher than the last and cleverly combined with a barbed-wire fence.

Ah, yes, it just isn’t a real Mexican hike without stone walls and barbed wire!

Eventually we staggered into town, weary but triumphant: we had conquered the mountain and survived not one but two senderos!

Here I must mention that, despite the above description, I do greatly appreciate the hard work of Senderos de México and its many, many volunteers to put up all those signs, but it certainly would have been nice to have a good old-fashioned map as a backup!

I suggest that once you have found a trail you like on the Senderos website, you then search Wikiloc for a detailed map just in case one of those crucial trail signs has mysteriously evaporated.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.