Our interview with the lifeguard had come to an end. A spate of robberies along the beach had the locals concerned, and his testimony had told us just that.

The entire town depends on tourists, particularly the ones bringing dollars, and a surge in crime is poisonous. Being told to turn out your pockets at knifepoint tends to overshadow even the nicest of beach getaways.

The local consensus was that the cops were to blame. They laugh in the faces of tourists who come to report robberies, and the lifeguard says there’s no security after dark. For the bad guys, there’s free reign to target anyone they think might be vulnerable, and ultimately the victims are seen as the ones to blame. They know they shouldn’t be around here after dark, so what were they thinking? Of course, something like this was bound to happen.

With murders on the increase to boot, our interviewee didn’t hold out much hope for the future.

“But what about that coronavirus?” he enquired. “That’s terrifying.”

“Really?” I replied incredulously. “Thirty-five thousand murders in Mexico last year, and you’re worried about coronavirus?”

“Ah sí.” Hi didn’t miss a beat. “Pero la violencia ya se conoce” – “Yeah, but we’re acquainted with the violence.”

And he was right.

Thirty-five thousand murders in 2019 didn’t spring out of nowhere.

The year 2018 saw 31,000 killings, and that was a record year when it occurred. Ad nauseam.

All across Mexico, the violence has become so commonplace that of course an unknown disease, of unknown tendencies, is more terrifying to this man than the disappearances and violence occurring in his own locale.

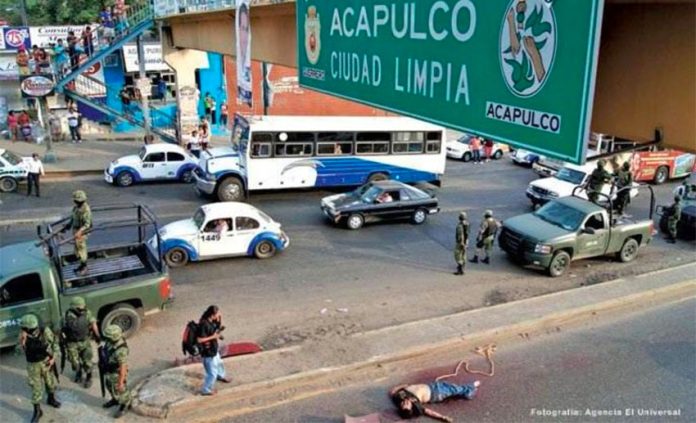

Three years ago I drove down to Acapulco from Mexico City early on a Friday morning to cover the town’s worsening violence. A local nota roja (crime and disaster stories) reporter friend had advised me that for best results, it was best to come around the weekends, and on a quincena (the fortnightly payday).

We saw seven bodies that day. Four discovered in a clandestine grave, two kids shot as they hung around on the wrong corner, and a man sitting in his car in a neighborhood close to the beach, shot through his window, his head slumped on the interior glass.

Seven a day was about the average, my local reporter friend told me.

In mid-2019 I returned to Acapulco to do a similar story, and that same friend, who says he’s seen more than 6,000 murders in nearly a decade of covering the violence, says the daily murder rate is better.

“Now it’s two, or one,” he told the camera. “Sometimes even none.”

But the city has become so numb to the bloodshed that locals barely bat an eyelid. Our interview was at the site of that day’s only murder (it was a Tuesday), and where the body had been, a large pool of congealed blood sat curdling in the afternoon sun.

“That’ll be cleaned up when the streets sweepers come through. People come by to have a quick look, and then get on with their business,” he said. “They just don’t care.”

Just how much does this apathy and stoic acceptance that violence is a fact of life in Mexico contribute to the issue?

My question was answered during the reporting of that same story.

The friend of a murdered student told us of her experience, and the self-loathing she experienced during the mourning process.

“Did I do anything to protest the death of my friend?” she demanded of herself. “No, because I was scared of something happening to me.”

“It’s so easy to criticize people who do nothing until you live through it. Until someone you love …” She didn’t finish her sentence; she didn’t need to.

I come to no judgement on the people, nor offer any broad conclusions about the nature of Mexican society. Perhaps the violence has always been here, perhaps not. But it seems we can’t see the bodies for the trees.

Alasdair Baverstock is a freelance foreign correspondent and reporter for CGTN who has covered Mexico and Latin America for nearly a decade. You can follow him across social media at @alibaverstock.