A few years ago, any encyclopedia — remember those? — would have told you that the longest cave in the world was the Mammoth Cave system in the United States. The combined length of Mammoth Cave’s passages would have depended on the year of the encyclopedia’s publication, as people made more and more discoveries about it.

As of this writing, on May 28, 2023, that system is measured at 685.6 kilometers (426 miles) long. But today, the worldwide community of cave explorers — speleologists, as we call ourselves — is starting to suspect that the longest cave in the world lies not in the U.S. but in Mexico.

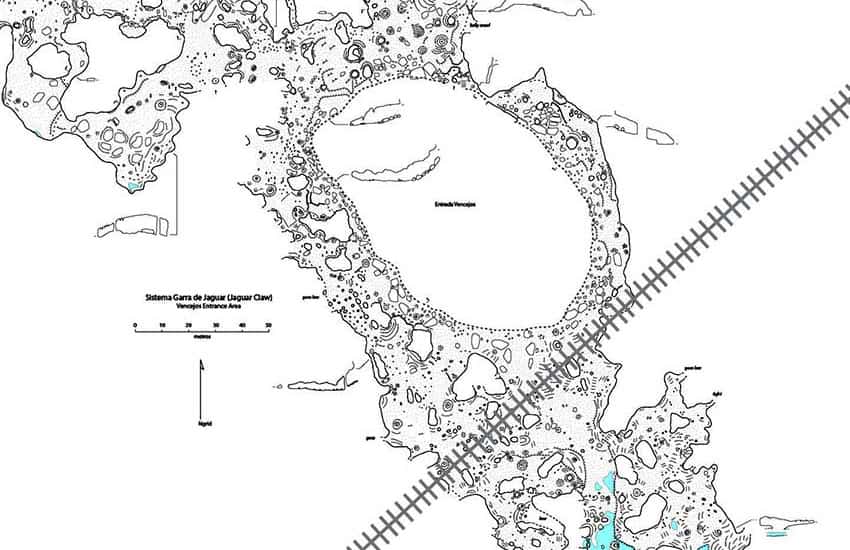

Cave divers have been exploring and mapping southeastern Mexico’s cenotes — natural sinkholes exposing groundwater — for years, discovering kilometers of underwater passages and linking them together.

At the same time, other researchers were mapping the region’s dry caves. As the various groups have compared their findings, they are discovering that the wet and dry caves are much more interconnected than previously suspected.

Some experts even suspect that the caves of the southeast are entirely linked.

“There’s only one cave in Quintana Roo,” says cave management specialist Peter Sprouse, who has been studying the area for years. “It’s just a case of connecting all the pieces.”

The biggest of those pieces is the 436-kilometer long Ox Bel Ha system, followed by Sac Actún (386 km). To these, Sprouse believes, will probably be added 29 other systems already mapped in Quintana Roo.

All of the above, when totaled, add up to a megacave that’s 6,898 km long (4,286 miles).

So there it is: Mexico houses what could be the longest cave in the world…and what are they building right on top of it?

Ah yes, we all know: the Maya Train. But what only a few of us know is the result of building a train track on top of karst.

Karst is a kind of terrain formed when bedrock made of rocks like limestone and gypsum is dissolved by water. For speleologists, it’s that lovely kind of terrain where caves are likely to be found, and it typically looks like Swiss cheese, full of interconnected holes and topped with sharp, pointy prickles.

This means that anything accumulated on the surface of karst, like fertilizers, pesticides or anything leaked from a cesspool or spilled from a tanker, will be washed directly into the aquifer within seconds after a rainfall.

In Europe, legislation regulates the construction of roads on top of karst. For example, a trench plus holding tanks must be built on both sides of a highway in a karst area in order to collect the kind of hazardous materials that recently caused havoc in East Palestine, Ohio — where 100,000 gallons of dangerous liquids were spilled from a derailed train.

To make matters worse, the aquifer housed inside what might come to be recognized as the world’s future longest cave is still mostly unpolluted.

So I decided to gather together the opinions of a few speleologists who work in Mexico, as I believe their ideas count more than the comments of those who have never trod (or swam) beneath the surface of our poor, besieged planet.

Geologist and speleologist Chris Lloyd has explored and surveyed caves in Quintana Roo over many years and has come to agree with Peter Sprouse that the region’s many caves are in fact one system.

“What is the Maya Train doing to those caves?” I asked him.

The Maya train, he told me, is “obviously… affecting all of the caves that it goes over.” “There’s already been one collapse along the corridor where the train is going, and there will undoubtedly be more collapses of existing caves. One of the caves I surveyed in that area has a 30-meter-wide entrance, and the train goes over it, right over the open space.”

Another problem that Lloyd pointed out is related to that huge aquifer housed inside the cave system.

The problem, says the geologist, is that the new train track is going over the higher part of the aquifer, while the existing roads and population centers are close to the coast, at the lower end of the aquifer.

“So water goes into the aquifer through the jungle, and it leaves the aquifer near the coast,” he says.

That water, Lloyd points out, is unpolluted because no one lives in the jungle. But the Maya Train has created new access points, and in many places there will be a road next to the railroad tracks.

“Whatever purpose it may have,” says Lloyd, “it is still a road, and people will use it. They will be building on properties out in the jungle. Eventually, whatever is built above the aquifer will pollute it.”

This aquifer, points out Sprouse, is more accessible to humans than any other on the planet.

“Near inhabited areas, you can dive into this system and see a pipe coming down through the ceiling of the cave with feces and toilet paper coming out. So anything encouraging more development without waste management is going to have a negative impact.”

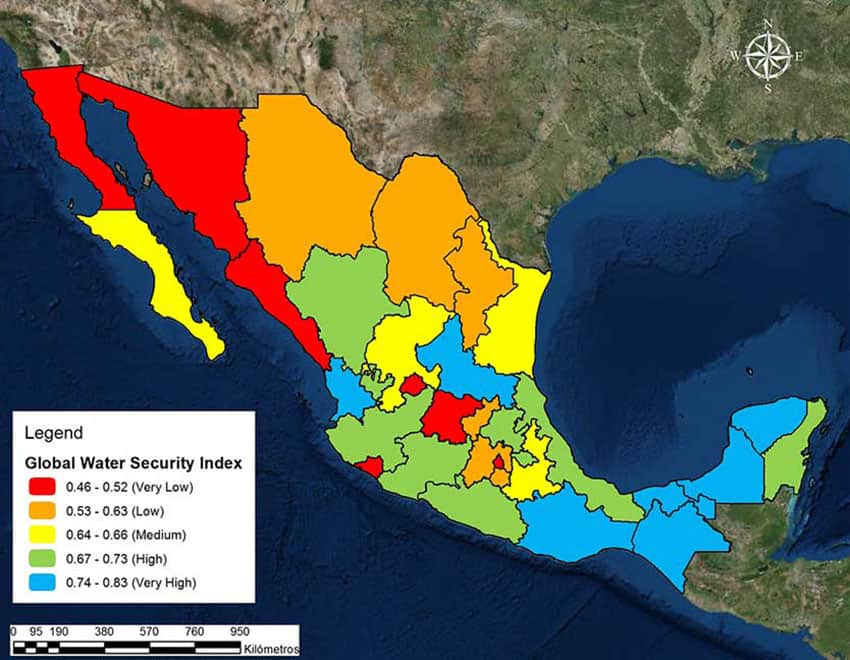

The Yucatán aquifer, explains geologist/speleologist Ramón Espinasa, is Mexico’s biggest, and one of the largest in the world, lying under one of the planet’s largest stretches of karstic terrain.

“The train is not the last problem of this aquifer,” says Espinasa. “We are just at the beginning of the problem. Once you have that train working, it’s going to attract more people. You are going to have more growth, more towns and more pollution of the aquifer that they are drinking from.”

Espinasa also backs the single-cave-system theory.

“It’s sad that they are going to harm the world’s largest cave, but it will survive. However, contamination of the aquifer is the real problem. The aquifer only needs one contamination point to foul up the whole thing. Because this is karst, there’s nothing between the surface and the water to filter the contaminants.”

Mexico will not need just strict regulations to prevent contamination of this aquifer: it will need literally the strictest regulations the world has ever seen. This is the message that Mexico’s speleologists and geologists want to convey to the country’s president.

The Maya Train is located right on top of the nation’s most precious aquifer, a karst aquifer that will be extraordinarily difficult to protect. Are you ready to take on this Herculean task, Mr. President?

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.