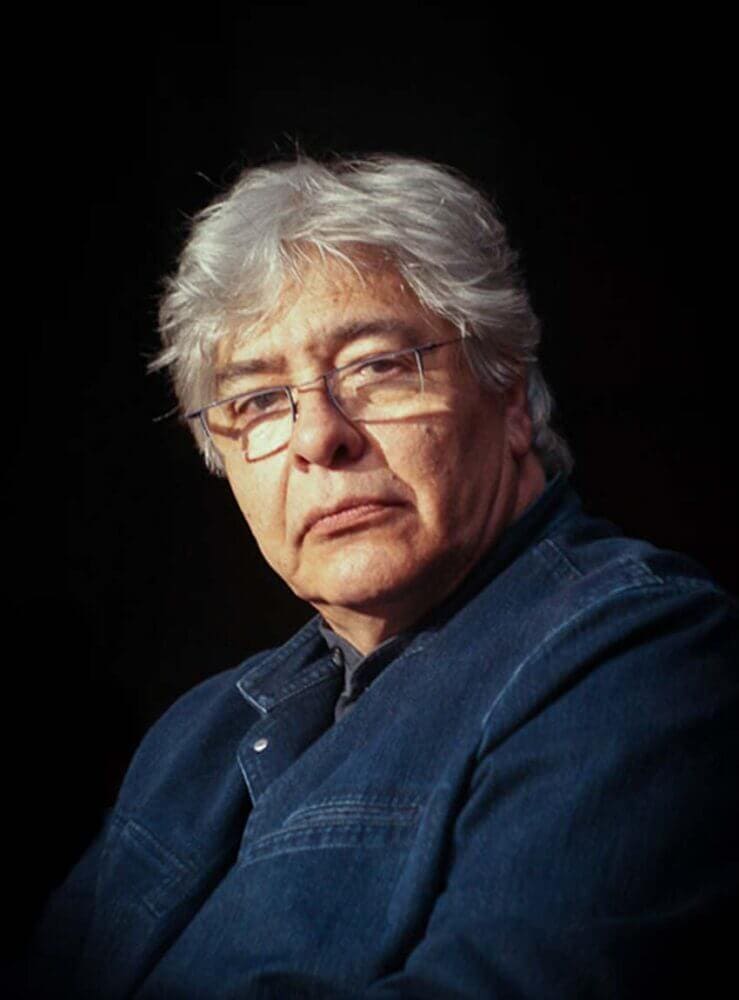

There is a very good chance that you have seen this artist’s work, but have no idea who he is.

Drive into and around metropolises such as Mexico City, Chihuahua, Monterrey, Guadalajara, Cancún, Veracruz, Torreon, Campeche, Toluca, Cuernavaca, Colima, Chetumal, Nayarit, Villahermosa and more and you will see at least one of the monumental sculptures by the Mexican artist known best as Sebastián. They have a distinct abstract or semi-abstract style; once you see a few, you will recognize others.

Many of the pieces are enormous, meant to make an impression on those visiting the city, either as they enter or as they arrive into important areas. College campuses, corporations and other organizations also see value in his work to make statements about themselves and their ideals.

Although his work can be found in many parts of the world, by far his most common and most loyal patrons are the public and private entities of Mexico. He gives even Mexico’s obsession with mural painting a run for its money — no mean feat in a country where Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo are still the king and queen of the fine arts.

The main reason for the popularity of Sebastián’s works is that they are uplifting rather than political and easy for the general public to relate to.

Sebastián’s personal history could have steered him in a very different direction. He was born Enrique Carbajal Gonzalez in 1947 in the little town of Santa Rosalía de Camargo, Chihuahua. He was accepted into Mexico’s National School of Fine Arts (today the Faculty of Art and Design of UNAM) in 1964, working several jobs to get through school. More importantly, he was a student during the demonstrations that led to the Tlatelolco Massacre in 1968.

Rounded up with other protesters, he spent two weeks in a military prison not knowing if he would ever be released. He had reason to worry; more than a few student activists disappeared during this time — their fates still not known today.

He was already highly dedicated to his craft during his school years, renaming himself “Sebastián, the sculptor” (a reference to St. Sebastian by Botticelli). Upon finally being released from military custody, Sebastián became obsessively prolific, driven by the aim of making an impact both in Mexico and the world.

But Sebastián prefers to use his art to help “diminish the suffering of people” rather than make political statements, focusing on providing inspiration to the human spirit to help get through the hard times.

His “gate” sculptures are designed to welcome those coming into a city. Famous works of this type include the gates of Chihuahua and Monterrey and, in the case of the border city of Matamoros, the gate into Mexico itself. Those destined for city centers, marinas and the like often depict something related to the city or region. These include the sailfish sculpture in Manzanillo, Colima, and the “hungry coyote” sculpture in Ciudad Nezahualcoyotl, México state.

A number of cities have adopted his sculptures as official city symbols, such as those for Ciudad Nezahualcoyotl, Chimahualcan, México state, and the Japanese cities of Tsuro and Kadoma.

In a country as dependent on tourism as Mexico, his works in visitor destinations such as Cancún, Ixtapa, Los Cabos, Loreto, Huatulco, Manzanillo, Cozumel and Playa Espiritú play a significant role in bringing visitors and helping them remember their stays fondly. Former Secretary of Tourism Enrique de la Madrid said that Sebastián’s work has “…raised the status of [Mexico’s] name in the world.”

His most famous piece among Mexicans is the relatively modest Caballito, at only 28 meters in height, located in front of an office building on Paseo de Reforma in Mexico City. It is a modern reinterpretation of the famous equestrian statue by Manuel Tolsá in 1803 found in the same city.

Despite his young age, Sebastían’s attitude towards art is more in line with the Ruptura art movement of 1950s Mexico than the politically and socially-charged movements that followed in the 1970s and 1980s. The Ruptura was about breaking with muralism of Diego Rivera and company, towards art that was more international, abstract, apolitical and even looked towards scientific principles.

It was quite controversial but eventually found favor with authorities as the avant-garde moved toward works that were anti-government.

Sebastián does not limit himself to monumental sculpture, dabbling in many types of expression including installations, digital art and even jewelry making. He has exhibited in major museums all over Mexico, the U.S., Europe and Asia and has lost count of the number of works he’s produced.

At 74 years of age, he has no interest in slowing down, still living and working hard in Mexico City. “For the artist, there is no retirement, since if you retire, you are no longer an artist,” he said.

He does admit that he is at the age where the documentation and preservation of his past work is now important and has established a foundation and museum in the city of Chihuahua to this end.

He has no problem being remembered for his monumental work, stating, “Monumental urban art is not a fashion, nor is it a way to exhibit [artistic] tendencies … It is a human condition, a necessity of the human spirit since [we lived in] caves.”

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.