As the Covid-19 vaccine rollout continues across the world, organizers can find lessons from a historic vaccination endeavor in the Spanish Empire during the 19th century.

The Royal Philanthropic Vaccine Expedition — informally called the Balmis Expedition after its leader, Spanish physician Francisco Javier de Balmis — vaccinated hundreds of thousands of people against smallpox, including in Mexico, principally from 1803 to 1806. It is widely viewed as the first-ever global public health initiative.

In Mexico, which was then part of the colony of New Spain, the expedition traveled from Veracruz to Acapulco, making stops in such major cities as Mexico City, Guadalajara and Oaxaca. Its achievements would endure after the country’s independence and inspire a 20th-century campaign against polio. Now scholars see parallels with the Covid-19 response.

“They had to solve the same kinds of problems we have today,” said Paul Ramírez, an associate professor of history and religious studies at Northwestern University, “logistics and transport, having to go to distant places, public trust, convincing people both healthy and sick why they did all of this.”

The reason was the dreaded infectious disease smallpox.

“Smallpox was an incredibly deadly disease,” said Gabriela Soto Laveaga, a professor of the history of science and the Antonio Madero Professor for the Study of Mexico at Harvard University. “Smallpox in the Americas, as we know, also decimated the populations.”

She noted that the indigenous population of Mexico City plummeted from an estimated 20 to 25 million before the arrival of Europeans to under two million a century later, with “many of the deaths due to smallpox.”

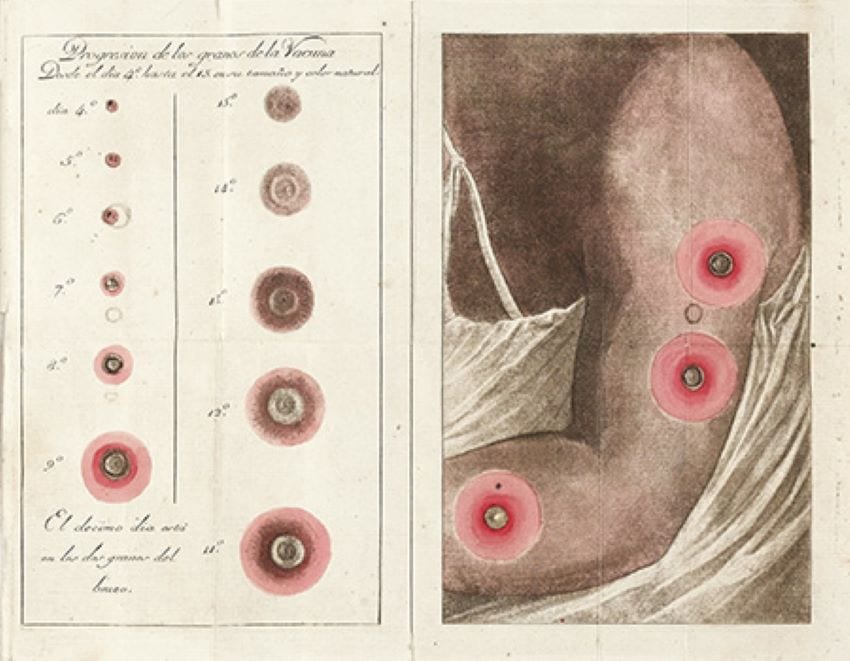

In 1796, the British scientist Edward Jenner discovered a vaccine for smallpox, the first vaccine ever. He published his findings two years later. The discovery of vaccination became known to King Charles IV of Spain — whose daughter suffered from smallpox.

Farren Yero, a postdoctoral associate in gender, sexuality and feminist studies at Duke University, said that Jenner’s discovery became known elsewhere in the Spanish Empire, including present-day Colombia and Ecuador, which were experiencing a smallpox epidemic and called for supplies.

“[But] the king dragged his feet for quite some time before responding to the request,” Yero said.

The Balmis Expedition sailed from La Coruna in November 1803. Balmis was a military physician who had spent time in Mexico during the 1780s. He had worked in a hospital in Mexico City and conducted research, notably with plants. Now he was returning on a much-larger-scale mission.

“The aim was to vaccinate every eligible Spanish subject,” Ramírez said, although he noted that “people who lived through a smallpox epidemic were already immune and couldn’t be vaccinated,” and that vaccinations were done “mostly with children under a certain age in any given campaign.”

The vaccine was actually transported through children who sailed with the expedition. Ramírez said they were orphans from Spain and estimates place their number in the low 20s.

“It could be incubated in the arms of children,” Ramírez explained. “It could be transported in people better than in glass slides. The best way was through human carriers.”

According to a 2004 article published in the scholarly journal Gaceta Medica de México, the expedition included a celebrated caretaker for the children — Isabel Cendala y Gómez. The article states that after stops in the Caribbean, the expedition made its first Mexican landings at Sisal, Yucatán, and then Veracruz. In Mexico, it said, Balmis traveled to nine cities, including Mexico City, to establish vaccination boards, to whom he provided the vaccine and taught how to vaccinate.

“He was smart,” Soto said. “He localized all efforts … selecting local people to do the vaccination. It was crucial for its success, not just in Mexico but across the world.”

“Just as today, there were a lot of protests,” she said, adding that to address opposition, Balmis “relied on the Catholic Church in a very religious Catholic country. What he did was rely on the local parish priests, the local clergy, to convince people.”

Balmis himself was “such a strong advocate of the smallpox vaccine,” she said. “He had seen … the devastation this disease brought.”

Yero called the expedition “kind of a restitution for bringing smallpox in the first place. Spain was responsible for introducing smallpox with the conquest of Mexico in the 16th century, and even prior to that with Columbus, really.”

Yero also said that slavery played a role in the vaccinations: Cuba sent three enslaved girls to Campeche as additional carriers of the vaccine at Balmis’ request, and following Mexican independence and emancipation, Mexico continued to bring in slaves from Cuba as vaccine carriers.

Access to the vaccine was also an issue, as has been the case with Covid-19 vaccines.

“It was supposed to be universal, supposed to be for everyone,” Ramírez said. “One piece of evidence in the archive suggests a rather different experience — the fact that lower-class people often complained [because getting vaccinated meant] a day off work, one day of wages, a financial hardship to them.”

He also said that where indigenous populations lived, certain communities remained overlooked because they were deemed too distant.

Balmis left for the Philippines in 1805, according to the Gaceta Medica de México. When he embarked from Acapulco, he brought a new group of 24 children from orphanages in Guadalajara, Fresnillo and Zacatecas to carry the vaccine. Ramírez said that not all the children came from orphanages and that in some cases, their parents were paid.

After the Philippines, Balmis went on to further stops including Canton, China (present-day Guangzhou), and the British island colony of St. Helena. He provided the vaccine to St. Helena even though Spain and Britain were at war.

Soto said that when Balmis finally returned to Spain “he was greeted as a hero.”

“In his final report, he calculated that between his expedition and sub-expeditions around the world, as many as one million souls were vaccinated,” Soto said. “It’s a remarkable number,” she added, although she acknowledges that its veracity is “not clear.”

Regardless of the number, she said, “if you think about it, they traveled mainly by ship, by foot in 1806. They circumnavigated the vaccinations around the world.”

As for what happened to the children who carried the vaccine, scholars are not entirely sure.

“I want to believe they were returned safely,” Soto said. “They may well have been. There were a lot of ships going between Acapulco and Manila. It was a frequent shipping route.”

Yero said the children who went to the Philippines did make it back, although it is unclear what happened to the three slave girls who brought the vaccine to Campeche.

A few years later, Balmis returned to Mexico to monitor the vaccinations. By then, wars of independence were on the horizon across the Americas.

Yero noted the effects of the Mexican War of Independence on vaccinations.

“A lot of records were destroyed,” she said. “People later wanted to continue vaccination. They no longer had guides to doing it. They requested guides in addition to vaccines. There are letters complaining about insurgents burning records down.”

Ramírez said that “some organization and stability” was reinstated in 1817 and 1818, with vaccination campaigns resuming in the 1820s and 1830s.

“There were attempts to vaccinate throughout the 19th century,” he said. “It is an interesting story. Mexico ended up being at the forefront of preventive medicine at the beginning of the 19th century as a result of coordinated campaigns.”

Mexico finally eradicated smallpox nationwide in 1951, and the disease was considered eradicated worldwide in 1980. The late Mexican physician and Rotary International president Dr. Carlos Canseco used Balmis’ example in a subsequent international campaign against polio.

In a 1991 address, Canseco called Balmis “one of the great heroes in human history, because his feat made one thing clear to the people of the 20th century: the eradication of smallpox was not simply a beautiful dream, but a reachable, practical and noble idea.”

Now the Balmis Expedition has echoes for the Covid-19 response.

“I think adaptability is the main lesson,” Soto said. “They had a plan. The plan didn’t always work. What they needed to keep doing was vaccinating, with a mindset of vaccinating as many people as possible in as short amount [of time] as possible.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.