About 30 men — and three women — gathered in the early morning light and began loading their boats with what they’d need for a day working on the water: fishing line, hooks and bait for the fish. Some water and snacks for themselves.

They started working around 7 a.m. and won’t return until 4 p.m.

Acapulco, even on an early morning in late September, is hot and humid. In the afternoon, it is brutally hot and humid.

Fishing on a boat for seven hours with the sun beating down and reflecting off the water isn’t easy work. But it doesn’t bother these fishermen.

“We are accustomed to it,” Homero Gómez Ruíz said. “It is like if you work construction and are on the third floor outside of a building. It is not hard because one is accustomed to it.”

The fishermen on this stretch of beach belong to one of four cooperatives. “A cooperative is several boats,” explained Vicente Hernández, who is 59 years old and has done this for 35 years.

There are around 40 members in each cooperative, and each boat will typically head out into the water with three or four fishermen.

Members of the Las Hamacas cooperative use nets to catch fish while those in the other three use fishing line with a hook and a sardine attached as bait. No one uses a fishing pole. “It is better to just use a line,” Alfonso Rebollar Santana said. “It is more sensitive. You can feel the fish biting.”

It may be better, but one look at his hands shows that it’s not easy work. The back of one hand was crisscrossed with thin scars and most of his fingertips were scarred too.

Some boats, like Ruíz’s, leave in the early morning. Others, like Hernández’s, leave around 4 p.m., returning at 11 p.m. The boats working at night use lamps and flashlights to light the sea. “What is difficult is not sleeping,” said Victor Olea, whose boat goes out at night. “It wears out your body.”

When it’s time for a crew to put out to sea, logs are placed under the boat, and fishermen push it over them toward the water. When the boat has reached the water’s edge, most of the crew jump in, leaving just one person to make the final push into the surf. The boat is then paddled out some distance before the small outboard motor is cranked to life.

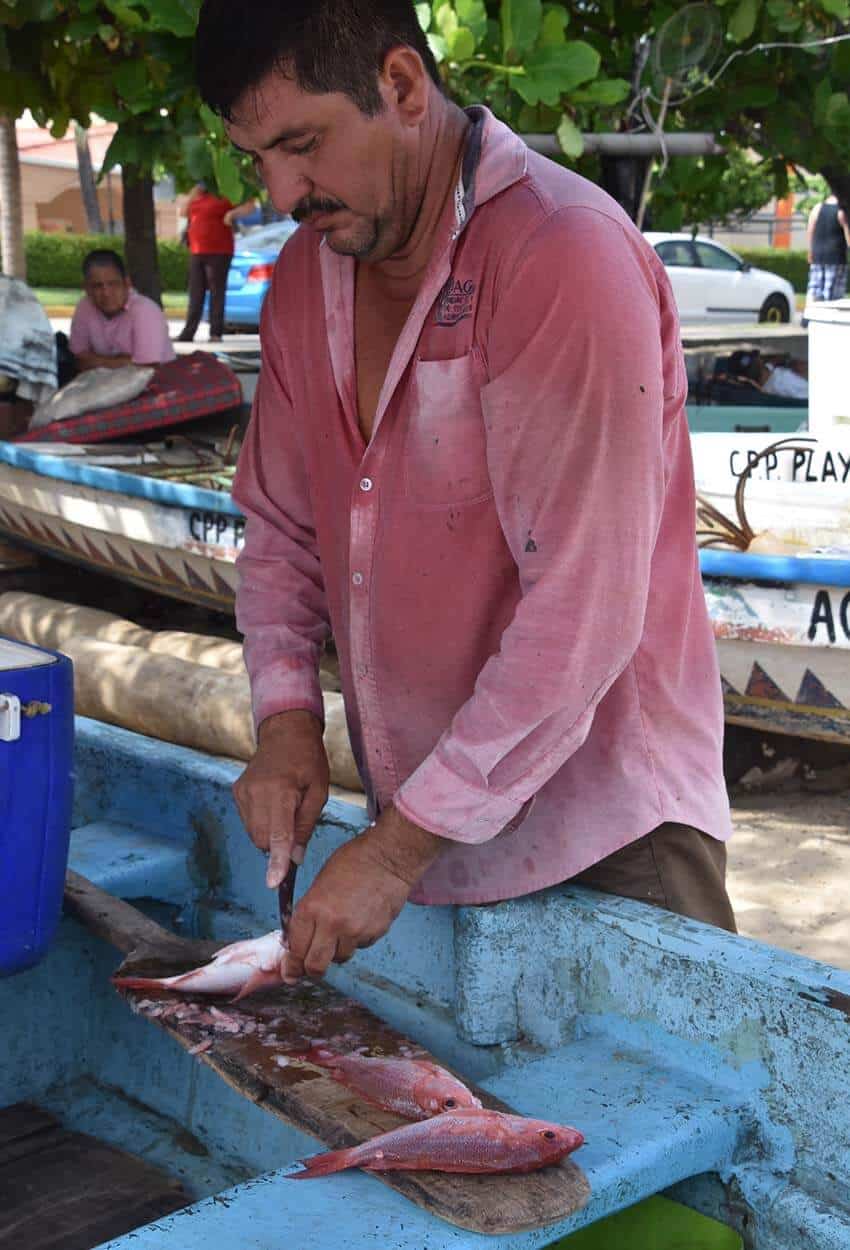

A crew returning after seven hours at sea push their boat onto the sand and then roll the boat up the beach on logs. Once the boats are parked, the catch is sorted and the fishermen are paid.

“In each boat, everyone helps each other, sharing whatever they earn,” said Bernardo Soto. When they set out for the day, no one knows how much they’ll make. “Every day, the money varies between 200 and 1,000 pesos,” said Pedro Brito Echeverría, “depending on what is caught, depending on the season.”

During a full moon, Soto said, they don’t earn as much because fewer fish are caught. “The fish don’t come to the surface as much,” he said. “The important thing is to have faith to fish.”

After the catch is sorted, most of it is loaded onto small carts and wheeled to local markets and small stores, but a few stands are also set up along the sidewalk that skirts the beach. Freshly caught fish are laid out on small wooden platforms, and people stop by to make their purchases.

Like everywhere else in the world, climate change is having an impact on the fishermen in Acapulco. “The fish are scarcer,” Brito said. “And it is thought to be due to climate change.”

He’s certainly seen the changes, having worked as a fisherman for 36 years, starting when he was 14. “Twenty years ago, we would catch double,” he said. “And the fish now are smaller.”

Because they’re never sure how much they’ll earn — and because they never earn very much — the majority of the fishermen work other jobs as well. Gómez is an administrator at the Autonomous University of Guerrero. Rebollar works in construction and as a gardener. Juventino Hernández García has an ironworking shop.

Fishing may not be lucrative work, but all the people interviewed said they were happy to do it. Lucinda González, one of only three women working on the boats, has fished for five years. She admitted that the profession is physical and difficult but, “I like the work,” she said. “I find it fun.” When asked if she’ll continue doing it, she said, “I will always work as a pescadora [a fisherman].”

Soto, who has done this for 12 years, also says that he has found his life’s work. “I do not have anything extra, and I do not lack anything,” he said. “I have everything I like, just like the fish do.”

Most of the people interviewed downplayed the dangers of fishing. “I do not think the sea is dangerous if one takes precautions,” Gómez said.

But at times it is indeed risky work. One can be surprised by an unexpected storm or strong winds. In fact, on August 28, two boats with a crew of six went missing. All are thought to have drowned.

“They were lost on the open sea,” Soto said. To date, only one body has been recovered.

Cooperatives have donated money to help pay for the search. They’ll help in other ways as well. “If someone dies,” Soto said, “everyone in the cooperative will help the family economically.”

There’s something about the sea that pulls certain people to it. Despite the dangers, the hard work and the, at best, meager pay, these people are out there, seven hours a day, day after day.

“It is the work of a family,” Brito said. “Generation after generation. Yes, the work is dangerous, but the work is carried in your blood.”

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.