The Austrian-born anthropologist and historian Eric Wolf once complained that for a long time, archaeologists in Mexico and Central America had become “shardists” and “pyramidiots,” whose archaeological horizons were limited to dating and classifying pieces of pottery or restoring pyramids for tourism.

A leader in opposing this trend was American archaeologist Phil Weigand, who spent most of his life studying the people who created western Mexico’s curious Guachimontones or “circular pyramids.”

Weigand brought a more holistic focus to his work, stating that his professional goal was “to be an anthropologist — not an archaeologist, not an ethnologist and not an ethnohistorian, but all three of these at the same time.”

Weigand laid down his trowel in 2011, but his spirit lives on in the work of his friend and colleague Dr. Eduardo Williams, researcher and professor at El Colegio de Michoacán. Williams has been putting the concept of ethnoarchaeology into practice for decades, using ingenious strategies.

For me, the term ethnoarchaeology is anything but self-explanatory and I hesitate to use it here for fear of turning people off — which would truly be a shame, because the word simply refers to a common-sense way of looking at ancient artifacts and buildings.

Every visitor to an archaeological site inevitably asks the guide, “What did the people who lived here do with these things? What were these people like?” Likewise, every historical novel or period drama about ancient peoples attempts to portray their human side: their strategies for survival, conquest or simple well-being, their struggles, successes and failures.

Ethnoarchaeology simply restores the humanity and culture of the maker to the stone axe or shaft tomb.

After earning a PhD in archaeology from the University College of London, Eduardo Williams settled in at the Colegio de Michoacán and put his mind to finding research projects within the financial limits available to him as a member of the Colegio.

“I told myself I needed projects that were easy to do in terms of resources and expertise, that didn’t cost money, and that I could do on my own without help from anyone.” A solution to his problem came from a book called In Pursuit of the Past by Lewis Binford, a pioneer in anthropological archaeology who studied modern-day Nunamiut (Eskimo) hunter-gatherers in Alaska, in order to better understand the behavior of their Paleolithic counterparts, through ethnographic analogy.

“I saw I could do something original, never before done in the history of west Mexican archaeology, and I could start doing it among friends of mine making pottery in a Tarascan village just half an hour from my home. While my colleagues had to find lots of money for their excavations, all I had to pay was the cost of a tank of gasoline.”

A few years before Williams’ arrival at the Colegio, Dr. Phil Weigand had joined the faculty.

“Phil Weigand was a true Renaissance Man. He crossed the boundaries of the historical and anthropological understanding of western Mexico, and I felt an instant rapport with him. When I told him about my project with the Tarascan potters, he had an immediate reaction, because he had been working with potters in San Marcos, Jalisco.

“So, I didn’t have to explain anything. He read my thoughts and told me what to do. So, we had a very good start as colleagues, right from the beginning and soon became fast friends.”

Eduardo Williams’ investigations of modern-day Tarascan potters led him to study the lives of salt-makers and fishers, as he calls them to avoid gender prejudice, many of whom, it turns out, still follow a lifestyle and traditions passed along from generation to generation, in many ways unchanged from pre-Hispanic times.

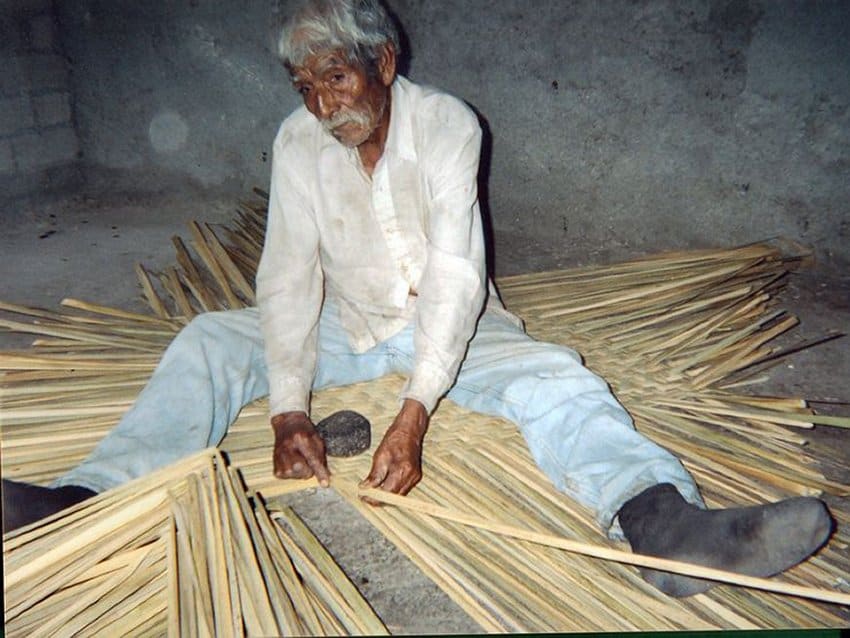

“At Lake Cuitzeo,” he says in his book, La Gente del Agua (Water Folk), “I found people using a stone hammer and anvil for basket-making. Now this technology goes back 10,000 years. These are the oldest kinds of human-made instruments known in archaeology.

“Once the basket makers cut the reed, they have to split it lengthwise. Then they use the hammer to mash it, so it becomes flat — and then it can be used to weave a basket. Just imagine the experience for an archaeologist to see artifacts that you know are thousands of years old being used today, right before your eyes!”

[soliloquy id="69212"]

On the shores of Lake Pátzcuaro, Williams actually found people who knew how to use the atlatl, the celebrated device for propelling a spear much faster than it could be thrown by hand alone and one of humankind’s first mechanical inventions (at least 10,000 years old, according to archaeological data).

“In the late 1940s, ducks by the millions used to arrive at Lake Pátzcuaro in early October,” fisherman Manuel Morales told Williams, “and on October 31 we used to go out in canoes to hunt them, with nothing but fisgas (reed harpoons) and el tirador (the atlatl).”

A second informant, Rogelio Lucas, offered to show Williams the techniques for manufacturing an atlatl, even though he had not made one since 1978. He also showed him how to prepare the metal point of the fisga and a special insert at the other end which fits into the atlatl.

Altogether, the craftsman used 13 different tools to make the two pieces, including a hacksaw and a vise-grip. Ancient atlatl makers would have had their own specialized set of tools (called an “assemblage” by Williams) to produce the same result.

Archaeologist Jeffrey Parsons says in his book The Last Saltmakers of Nexquipayac, “There are many traditional activities hovering on the edge of extinction that deserve . . . recording in Mexico and throughout the world. Few scholars appear to be much interested in studying the material and organizational aspects of these vanishing lifeways, and archaeologists may be virtually alone in making such efforts as do exist. In one sense this . . . is a plea to others to undertake comparable studies elsewhere while there is still a little time left to do so . . . .”

Eduardo Williams is one of those few scholars studying these vanishing lifeways. To learn more about his work, you can view a 165-page, well-illustrated, abridged version of Water Folk in excellent English at ResearchGate.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.

Photos courtesy of Eduardo and Teddy Williams.