The unfamiliar word “neoprehistory” recently sent me to an art exhibit in Guadalajara and then down an interesting rabbit hole about artifact looting in Mexico.

The exhibit was at the Phil Weigand Guachimontones Museum, located 40 kilometers west of Guadalajara, which presents the fascinating history of the people who constructed huge “circular pyramids” all around western Mexico 2,000 years ago. In addition, the museum always features an exhibit on some other topic related to archaeology.

Recently I learned that the latest of these changing exhibits is a presentation by the Neoprehistory Institute, a place I’d never heard of, featuring art by Ernesto Solana.

As I had no idea what the word neoprehistory meant, I phoned up Arely Orozco, the museum’s administrator, to ask her what the exhibit was all about.

“Saqueo,” she replied.

“Saqueo?” I repeated, my eyes widening.

The Spanish word means “tomb looting,” surely a more interesting topic than neoprehistory, whatever that was.

It turned out that the “Neoprehistory Institute” is an invention of Solana’s, part of the conceit of an art series that he began exhibiting in 2021. Meanwhile, the term “neoprehistory” doesn’t seem to be in usage in any dictionary or any other context I could find online besides two art exhibits — one by Solana and another in Milan in 2016.

Solana’s current exhibit is the second part of a series of works by the artist, which reimagines Mexican prehistory through art. But Solana’s current exhibit does more than reimagine: it also comments on Mexico’s complicated history with its prehistoric artifacts, particularly around the subject of tomb looting.

For the public, tomb looting might bring up dynamic images of Lara Croft and Indiana Jones, but for every archaeologist in Mexico, it literally conjures up nightmares.

“The display is about saqueo?” I confirmed with Orozco over the phone. “Okay, I’m coming to see it tomorrow.”

She was there waiting for me the next day, her baby Ana Paula in one arm.

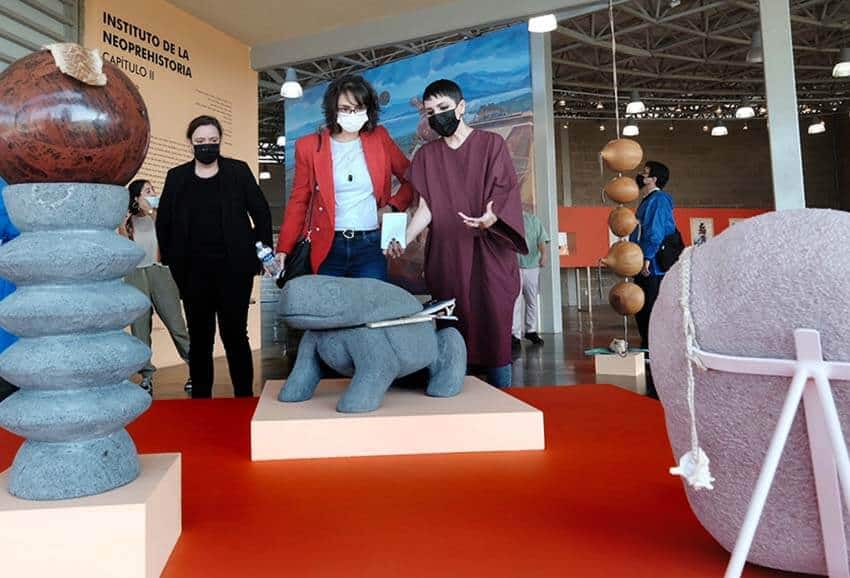

We walked over to the exhibit, which is entitled: Instituto de la Neoprehistoria Capítulo II. A big sign on the wall introduced Ernesto Solana and the theme he had chosen for our consideration. Buried in this explanation is a casual statement mentioning that the Neoprehistory Institute is not a real organization at all, but rather “an exercise in speculation.”

After reading this, I began to look at Solana’s work — and to understand.

Solana is an artist and sculptor, established in both Mexico City and Guadalajara, and it appears he has a great sense of humor. At the Guachimontones, he has found just the right formula to focus our attention — without raising a war cry — on a subject that is both serious and complex.

Orozco led me to a set of collages on the wall.

“With these,” she said, “Ernesto Solana is trying to engage us in a dialogue. His approach is very subtle, because for us archaeologists, tomb looting is a subject both painful and delicate.

“Each collage shows us a fantastic being — part man, part woman and part beast — entirely composed of pre-Hispanic art pieces now found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, in a room completely dedicated to the archaeology of western Mexico.“

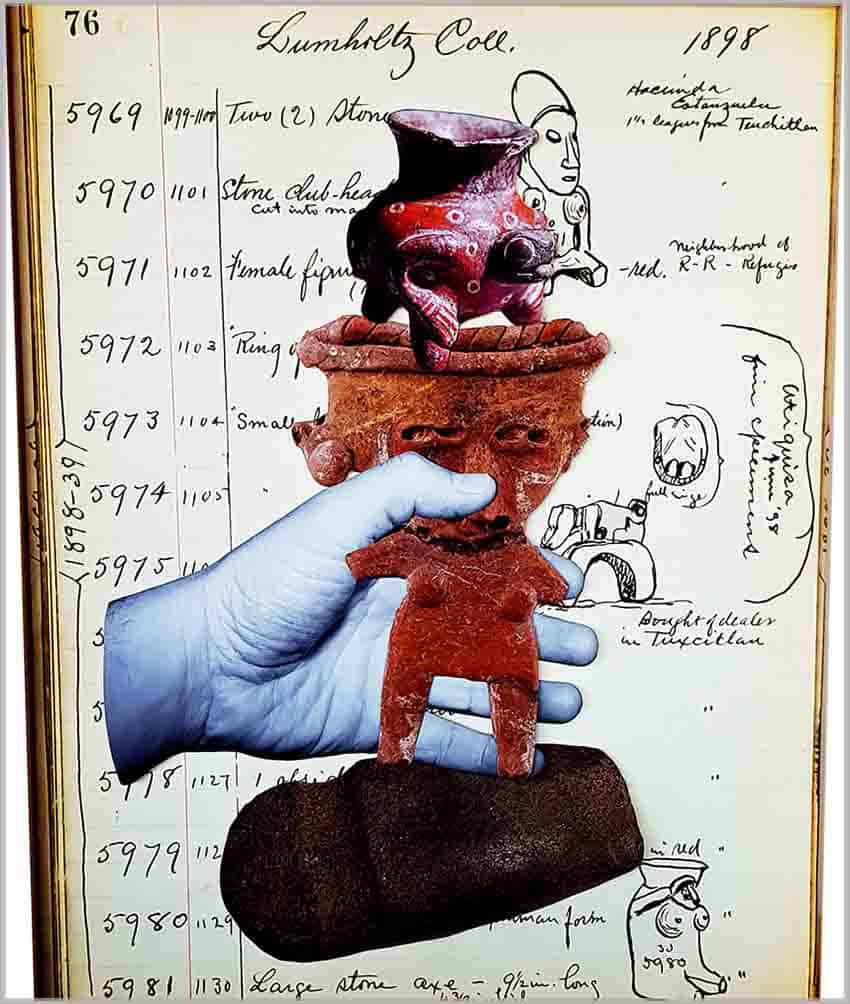

A few steps away, there is a similar set of collages, but these are superimposed on enlargements of pages from very old handwritten catalogs that describe, in English, thousands of artifacts illegally carried from Mexico to the American Museum of Natural History by explorer Carl Lumholtz and archaeologist Marshall Saville.

According to researcher Seonaid Valiant, they were able to avoid customs inspection thanks to the assistance of President Porfirio Díaz.

The curiously assembled artifacts in these collages are each accompanied by a giant hand. To me, the message seemed clear: Mexico’s patrimony has been handed over to someone else.

Just between these two sets of whimsical collages, there is a sort of display within a display.

Here — with no neon signs or flashing lights — we see a small figurine collection found in situ in western Mexico by archaeologists. These are figurines that looters never had a chance to get their hands on.

Again we are being given a message, and this time Arely Orozco spelled it out for me: “Just one of these pieces found in its original setting renders much more information than all the looted objects in the Met’s collection taken together.”

This juxtaposition of photos of looted objects spirited out of Mexico on either side of a collection of artifacts found and studied where they originally lay opens the door to the complex issue of monos (figurines), as they are called by the country people who stumble upon them by accident or deliberately hunt for them.

A person in possession of a mono might be a saqueador (looter) — who has found and removed the precious item from its original surroundings — or he might be the buyer.

If the buyer is a foreigner, off goes the figurine out of the country, and in most cases, so does every scrap of information about the piece. If, however, the buyer is a local coleccionista (collector), the piece will at least remain in the neighborhood.

Truth be told, what you see in most small-town museums in Mexico is almost always the personal collection of a local Don Pepe or Don Pedro.

Contrast all of this with one of those very rare events: when a tomb is discovered intact and the first people to enter it are archaeologists.

Such a thing happened in 1993 when an untouched tomb was found at a place called Huizilapa, Jalisco, just northwest of Tequila Volcano.

This shaft tomb was 7.6 meters deep and had two chambers. Six individuals were found, three in each chamber, together with offerings. Bone studies suggest that this was a family crypt.

The archaeologists who first entered the chambers were amazed to find over 60,000 artifacts inside — yes, 60,000! This was all the more remarkable because the depth of the tomb suggested that the people buried in it were not particularly important. (Some shaft tombs are over 20 meters deep.)

The body of one individual at Huitzilapa, says archaeologist Eduardo Williams, “was elaborately adorned with jade and shell bracelets, nose-rings, earrings, greenstone beads, carved jade pendants and a cloth sewn with thousands of shell beads …”

The tomb offerings, Williams said, also included pottery figures representing ballplayers and clay vessels decorated with geometric and zoomorphic designs which, when excavated, still contained food remains.”

Moving on to other parts of Solana’s exhibit, I came upon some sketches by British explorer Adela Breton of objects she drew in 1896 when she witnessed the looting of the Guadalupe Mound near Etzatlán, Jalisco.

In each case, the sketch is paired with a photograph — perhaps taken decades afterward — of the figurine Breton had depicted.

Were Breton, Lumholtz, Saville, the American Museum of Natural History and the New York Met looters — or collaborators with looters? Should Mexico’s wayward archaeological treasures be sent back to where they came from?

I had my opinion on the matter, but one day, I asked archaeologist Phil Weigand, popularly known as “the discoverer of the Guachimontones,” if Jalisco should ask the Art Institute of Chicago to return its collection of 2,000-year-old clay models (maquetas) depicting people interacting around the circular pyramids.

“Now is not the time,” he replied.” We don’t have the resources to keep those maquetas safe, but while they’re in Chicago, nobody is going to steal them.”

At present, the American Museum of Natural History is holding 50,000 pre-Hispanic artifacts from Mexico and Central America.

- Information on Ernesto Solana and examples of his art can be found on his website. For up-to-date news about the Guachimontones museum and archaeological site, as well as replies to questions, see the Guachimontones Facebook page

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.