Wearing an innovatively designed wetsuit, United States biologist and conservationist Forrest Galante in 2016 swam face to face with a crocodile off the Banco Chinchorro. In this region between Mexico and Belize, Galante had a unique opportunity to view American crocodiles in their natural habitat, thanks to a wetsuit that made him look like one of them.

“The more scary something seems to be, the more I’m interested in it,” Galante said. “Crocodiles are at the very top of that list.”

The wetsuit was designed in New Zealand using a strategy known as biomimicry. Different versions make the wearer look like different dangerous species, from sharks to crocodiles — instead of their prey.

This allows the wearer to get up close to these species, as Galante did when he and colleague Mark Romanov made the 2016 short film about the crocodiles, Dancing with Dragons.

“The fear factor gets in the way to have the opportunity to be face-to-face with one in crystal clear water,” Galante said. “Everybody has the misconception that they are totally merciless killing machines. It was a phenomenal, amazing experience, scary and exciting … It was a hands-on moment I live for.”

Galante has had many more such moments since then, including an incredible run of turning up living examples of species long thought extinct, on his Animal Planet TV show Extinct or Alive.

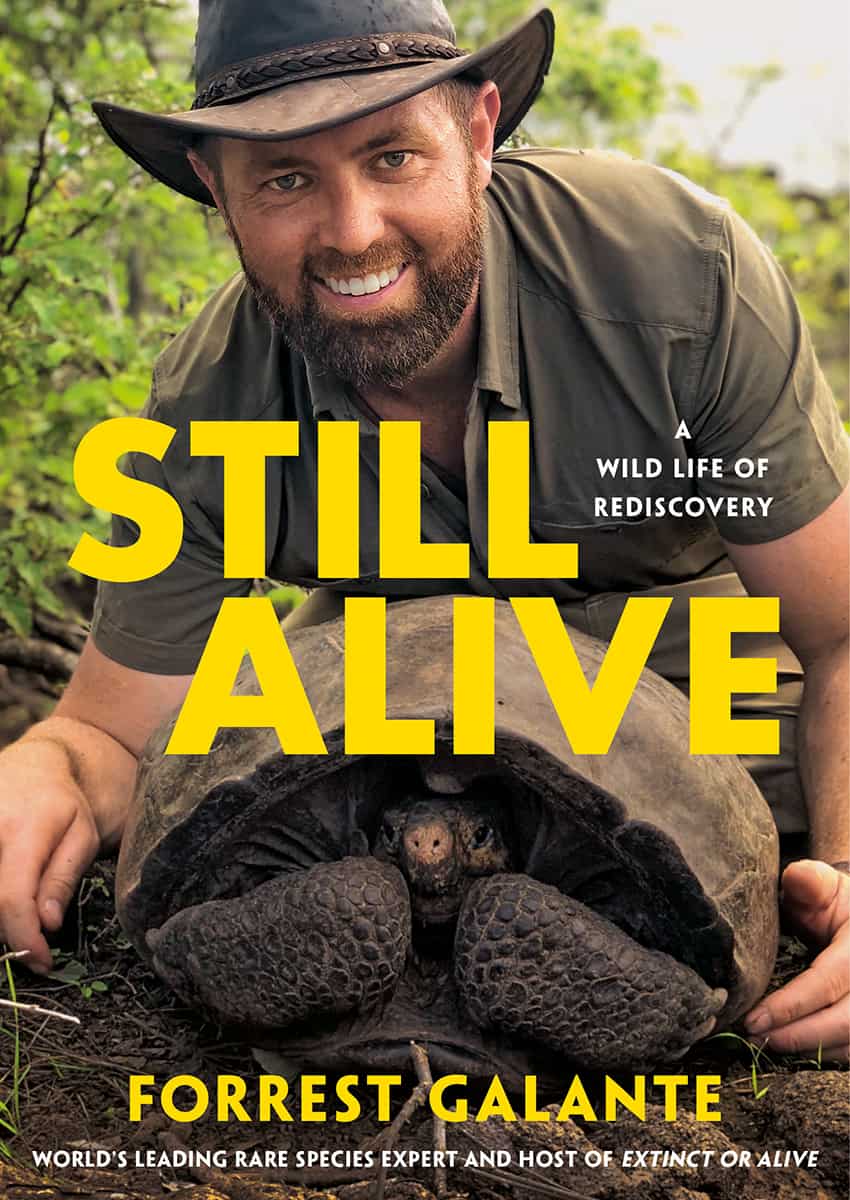

His new book, Still Alive: A Wild Life of Rediscovery, details those experiences. The cover shows him holding Fern, a Fernandina Island tortoise found on the Galapagos Islands and considered extinct for over a century.

Regardless of the medium, whether it’s books or TV, said Galante, his goal is “to inspire people to care about wildlife and conservation.”

At the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, he was in Indonesia, trying to help a crocodile trapped in a discarded tire. A letter from the president’s office shut down the rescue effort, and he left Indonesia.

Since then, he’s worked on Wet Markets Exposed, a TV show about these markets around the globe, including South America, Europe, Africa and Asia. Some have attributed wet markets as a cause of the novel coronavirus.

“Wet Markets Exposed is not necessarily just about wet markets,” Galante said. “It’s about how we as a species, human beings, decide to treat wildlife.”

And, he added, wet markets “are not evil” but “need to be regulated and managed, with no trafficking in meat” or intermingling of different species’ blood, urine or feces.

“They need sanitation, sterilization, management,” he said. “That’s the message behind Wet Markets Exposed.”

Galante said that the “only commonality, no matter where I was in the world, is my love of wildlife. It doesn’t matter if it’s elephants and lions in Zimbabwe [where he’s from] or newts and fish in California. It all includes a fascination with wildlife, my own story, and our place in the environment and ecology.”

He’s done “tons of work in Mexico all the time,” he said, including in the Sea of Cortés. “I absolutely love Mexico,” he said. “I’m obsessed with Baja [California].”

He is working with a group on conservation efforts related to the endangered vaquita porpoise in San Felipe. His swim with the crocodiles on the other side of Mexico got him wider attention.

“I made this crocodile film,” he recalled. “I had very limited experience in filmmaking. It was the first film I ever made [with] a very, very shoestring budget.”

He knew the risks.

“I grew up in southern Africa,” he said. “I always feared crocodiles, and rightfully so. A million people get killed by crocodiles. A million people fall victim to crocodile attacks. So I was very much taught to fear crocodiles.”

Yet, he pointed out, the wetsuit gave him “a little bit of a competitive edge.”

“I would not completely say I was reliant on the suit,” he said. “[But] using that approach, that technology, gave me a better sense of confidence.”

With his friend and partner Mark Romanov shooting from underwater, Galante focused on the crocodiles. “You don’t have control of the situation,” Galante said. “It was intimidating but also thrilling.”

Several years later, Galante showed the film to the History channel and used it to successfully pitch a new show, Face the Beast. It involved traveling to Myanmar to investigate a report that crocodiles had massacred 1,000 Japanese soldiers during World War II.

Meanwhile, Extinct or Alive has taken him across the globe in pursuit of surviving members of species long considered vanished — including when he found Fern on the Galapagos Islands.

Before that episode, Galante said, “I still hadn’t caught or tracked or found an extinct species,” although he said he had photographic proof of the existence of one such species, the Zanzibar leopard in Tanzania.

On the Galapagos, Galante, his team and local biologists looked for the elusive tortoise while navigating lava flows and “brutal, brutal heat,” culminating in an exciting discovery — “a pile of tortoise poop.”

“Shortly after,” he recalled, “we found a bedding site. Five minutes [after], even less, under a bush, I found Fern … She was like a rock with legs.”

He called her “the rarest animal in the world.”

“There was one of them, no one else except for her,” he said. “It was crazy. It was a wonderful, exciting experience.”

The find had a large global impact, he noted, with so much important hope for conservation. “She’s the poster child of global conservation, in a way,” he said.

Galante has since increased the number of species he’s rediscovered to eight. Sometimes there have been difficult moments — including what he called “bruised egos” on the Galapagos between his team and local scientists. Yet, he said, “everyone wants the same thing — promote conservation and wildlife.”

One source of frustration is the search for the Mexican grizzly bear, which continues to be classified as extinct.

“We don’t know if the Mexican grizzly bear is gone forever,” Galante said. “There’s some evidence loosely supportive of their existence. We don’t have anything concrete.”

For each extinct species he investigates, he uses a checklist of factors to see whether the conditions suggest hope. “Some of them check all the boxes,” he said. “The tortoise did not. Nobody had seen one for 114 years. It had four of five boxes.”

“The Mexican grizzly bear just doesn’t check too many boxes,” he said.

The bear species was not very abundant to begin with, he said. “It’s not like there were millions of Mexican grizzly bears,” he said. “The likelihood of them still being in existence is pretty small. It does not mean it’s not worth looking at. But the likelihood is already small.”

Yet, his overall quest is not always about the destination, he explained. “It’s about the journey.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.