When Arizona State University (ASU) archaeologist Michael Smith learned that the ancient Mexica (Aztec) terraces he was studying at a pre-Hispanic site in the Valley of Toluca had actually been built or significantly altered in the modern era, he recalled feeling dismayed.

“I was quite upset,” Smith said. “How do we figure out what the whole site looked like in the Aztec period? It required a detailed sort of geoarchaeological analysis to figure out.”

Smith, who is ASU’s Teotihuacán Research Laboratory director as well as a professor at the university’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change, was lucky enough to work with a research team to do just that. Together, they solved some historical mysteries in the process.

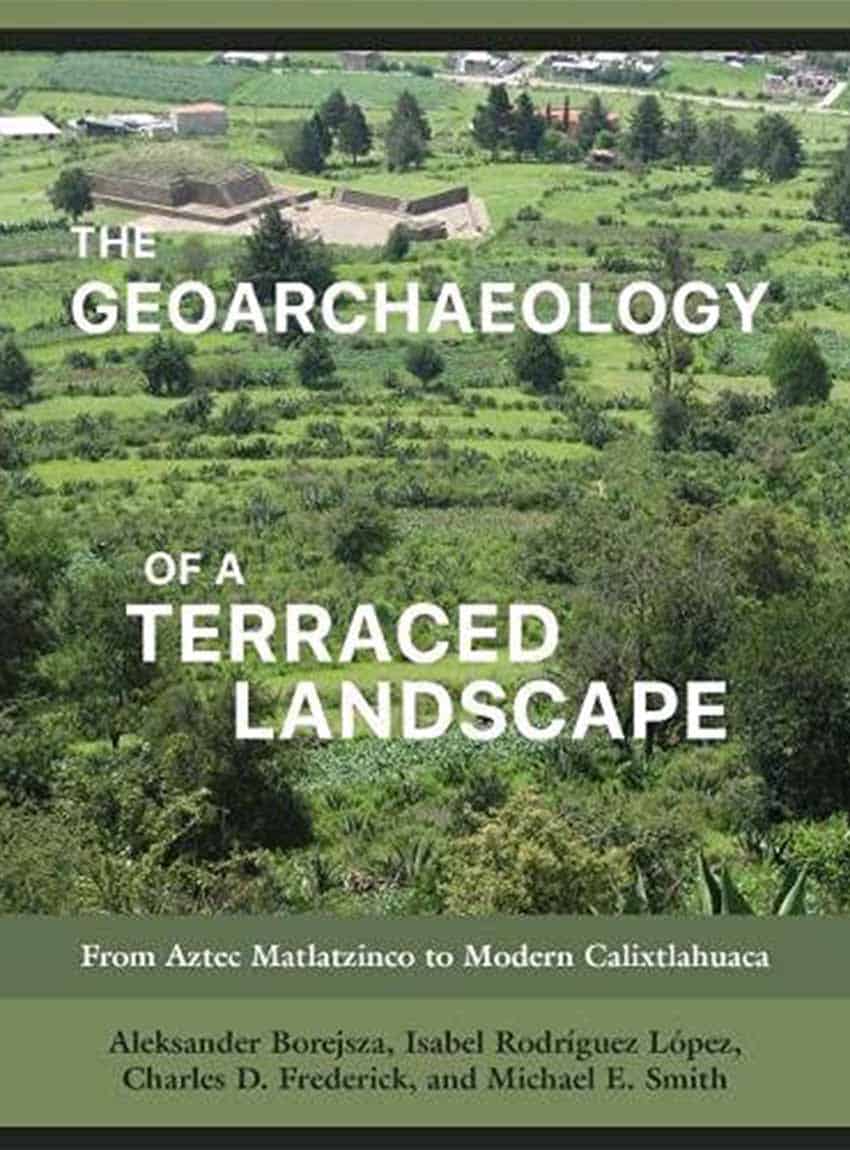

They explain their findings in a new book, The Geoarchaeology of a Terraced Landscape: From Aztec Matlatzinco to Modern Calixtlahuaca.

The indigenous settlement of Calixtlahuaca was occupied by several different pre-Hispanic groups at different times, according to the National Institute of Archaeology and History, but the period Smith and his colleagues were interested in was from A.D. 1100 onward, during which the Matlatzinca inhabitants were eventually subdued by the Mexicas in the late 1400s and then again by the Spanish in the 16th century.

The methods Smith and his team used are part of the multidisciplinary field of geoarchaeology, which applies techniques and knowledge from the Earth sciences to answer archaeological questions. The field draws from geography, geology, geophysics and more.

The team — and Smith’s coauthors — included University of San Luis Potosi archaeologist Aleksander Borejsza; archaeologist Isabel Rodríguez López; and Charles Frederick, a University of Texas at Austin consulting geoarchaeologist and research fellow.

“A lot of work on terraces in central Mexico and Mesoamerica is based on mapping terraces on the surface … not excavating them,” Smith said. “You can only say so much if you’re not actually digging them.”

He admits that their book is a “pretty dense technical volume, not for the fainthearted.” “There are a lot of gory details in it,” he quipped, “how terraces are built, created, maintained.”

It’s based on two seasons of fieldwork at the site, in 2006 and 2007, and nearly a decade of work of analysis of materials after that. The team’s archaeology work even included examining ancient maize kernels from the site.

“Maize and beans, that’s what we were expecting, the standard crops in central Mexican societies,” Smith said. “In a few places, homes had burned down, and there were some corn and beans that we’d see carbonized, thrown in charcoal and not consumed by fire, that we could recover archaeologically.”

Smith’s initial dismay upon encountering transformed terraces changed to fascination as he and his colleagues uncovered what had happened in the 19th century.

“That history is important,” he said. “It explained to us the nature of the houses and features we found.”

Searching for Aztec houses had originally drawn Smith to the area in order to investigate daily life, agriculture, social patterns, economic processes and urban organization at Calixtlahuaca

“We found a number of houses that we were able to excavate,” he said, with these homes showing “heavy use of wattle-and-daub construction.”

The site was continuously occupied from 1100 to almost A.D. 1600 — a time period that predated the rise of the Mexica empire and ended after the Spanish conquest. “We do know the region of Calixtlahuaca was really engaged in various kinds of production of tools and metals, traded with many parts of central Mexico and was conquered by the Aztec Empire,” Smith said.

To live and work on the hilly landscape, its indigenous inhabitants built terraces, an ancient way of adapting a hilly landscape for human existence; manmade level surfaces on a slope allow opportunities for farming, habitation and even channeling excess water off the slope during a storm – a necessity in places with a rainy season.

Following the Spanish conquest of the Mexica, the colonizers compelled Calixtlahuaca’s inhabitants to leave the community and help build a new city nearby — Toluca. The terraces were abandoned. “There was severe erosion,” Smith said.

Indeed, a Mexica royal palace at the bottom of a hill had been buried due to what Smith calls a “massive erosion episode in the whole landscape.” The palace was only rediscovered in the 1930s by Mexican archaeologist José Garcia Payón.

Smith and his team also discovered another dramatic and mysterious change: on the slopes, seemingly every other terrace had been systematically destroyed. On those that remained, the team found well-preserved evidence of Aztec houses, but they sought an explanation for the vanished terraces.

According to Smith, large landowners in the 19th century began expanding their haciendas, forcing smaller farmers to look elsewhere to graze cattle, including in Calixtlahuaca. Yet, problems emerged as they turned to these terraced lands.

“In 19th-century rural areas, you had farming by a plow pulled by oxen,” Smith said. “Aztec terraces were too narrow. Oxen couldn’t turn around. [The farmers] destroyed many of the terraces to make [the others] wider. Every other terrace was destroyed, altered. They built up the remaining [ones] to make them larger. We see double-wide terraces … that allowed people to farm with 19th-century technology.”

Before this development, he said, “People would graze cattle, grow some crops” on the landscape but “not actively farm the site itself.”

At the site, Smith served as director of the overall project. Borejsza and Rodríguez worked with him on excavations, focusing on the water channels there. Frederick contributed his knowledge of ancient terraces in other parts of the world to address another mystery: the reason for the recorded erosion.

Frederick attributed this to the abandonment of the terraces for hundreds of years following the Spanish conquest.

“[Frederick] worked in Greece and the Mediterranean area on ancient terraces,” Smith said. “He recognized the situation [in Calixtlahuaca] and sort of the likelihood that it was the cause of the erosion.”

As Smith said, “You’ve got to keep the terraces up. After a rainstorm … you’ve got to build them back up again. During the rainy season [in central Mexico], it usually rains five to six days a week. It rains really hard, very hard … During that season … if you don’t actively work your terrace, prepare for this, fix a break when it occurs, it can really destroy a whole system.”

After their centuries-long disuse, the terraces of Calixtlahuaca have gotten a second life in the modern era.

“People still farm the terraces,” Smith said. “Originally built by Aztec people, they were modified in the 19th century, and they continue to be modified — people still do this today.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.