The town of Pihuamo, Jalisco, is located 150 kilometers south of Guadalajara. “Somewhere near Pihuamo, there’s an iron mine,” we had been told, “and along the road to that iron mine, there is a bottomless pit.”

Well, cavers love bottomless pits, if only for the fun of rappelling down them and a few minutes later shouting, “Hey, I’m at the bottom already. You call this deep?”

So off we drove to Pihuamo, where we had no problem finding the road to the iron mine because alongside it is a very high and impressive teleferico (aerial tramway) transporting 650 containers brimming with iron ore through the air.

“Do you know el pozo sin fondo [the bottomless pit]?” we queried a local shopkeeper.

His eyes lit up. “Mira no más [look no further]. You have heard about our bottomless pit way up there al otro lado [in the United States]?”

“Of course,” I replied.

“Okay, amigo. Bienvenido and drive up the road toward the mine until you come to a place called Fortín, and there you will find the now internationally famous pozo.”

The pueblito (a town with a population of 10) called Fortín was marked by a little shop selling refrescos (soft drinks). We asked for cold beverages and sat down with the owner, Don Rafael.

“El Pozo sin Fondo,” he said, “is back down the road a bit, next to a big pile of garbage.”

Ah, I thought, the local dump! What else would people do with a bottomless pit?

We found the dump without a problem, and my wife Susy walked up to the edge of the hole, which was about four meters in diameter. “I can see the bottom from here!” she complained. “Who are they kidding?”

Hoping to find an extensive cave system down below, we rigged the pit for rappelling.

The supposedly non-existent bottom turned out to be 28 meters below the surface. I was surprised to find not much garbage in it, but this was explained when I proceeded to the lowest part of the room, where I found a vertical passage with smooth, shiny walls.

“Obviously,” I thought, “a lot of water goes down this hole and — I bet — a lot of garbage too. No wonder they thought it was bottomless.”

I slid down the lower passage for 16 meters before the tube got too tight to continue, but continue it did. The surface of this passage was coated with rippling white flowstone, suggesting that below us there must be plenty of karst, the kind of limestone you get where caves abound.

Inspired by what we had seen, we went back and asked Don Rafael if there were any other caves in the area. “¿Cuevas?” he said. “Pos sí [well, yes], there’s a big one down by the river.”

A few weeks later, we were back again. “Don Rafael, remember that cave near a river you told us about? Think we could find it if you give us some directions?”

“Nope.”

“Er, any chance you could show us where it is?”

“Sure, anytime.”

“Oh … well, er, how about today?”

“Busy today.”

“Tomorrow, then?”

“Busy tomorrow también.”

Since Don Rafael himself had told us that one could easily spend all day wandering inside that cave, none of us were ready to give up so easily. After another hour of chit-chat with a lunch break in between, we finally talked him into “taking us partway.”

The river in question is the Pihuamo, reachable after a two-hour brisk hike down into a wide, lonely canyon said to be the home of animales de uña: pumas, mountain lions, etc. Shade trees dot the shallow river, which sometimes cuts through beautiful, massive chunks of limestone.

Although the heat was stifling and it felt like our brains were frying, we fairly flew down the hillside and headed upriver. The entrance to Don Rafa’s cave turned out to be small and easy to miss, which was a bit of a letdown until we stepped inside …

It’s been a long time since we’ve seen a cave in Jalisco anything like this: a smooth borehole four to five meters in diameter that reminded us of a train tunnel. Stalactites hung from the ceiling like great drops of hot fudge.

As Don Rafa had no name for this place, we decided to call it La Cueva Chocolate.

Because we had taken our guide away from his work (naturally, he hadn’t stopped at partway), we resisted the temptation to see more of the cave and headed back up the steep hill to tiny Fortín.

The following weekend, Luis Rojas and I were back in the area with the intention of camping near Chocolate Cave. Don Rafa had promised to join us there the following morning for breakfast and a tour of the cave, inside of which he had never dared to venture.

At the riverside, we filled our canteens with fresh spring water and then stored our backpacks inside the cave entrance. Soon we came to a short side passage, where we discovered a chinche hocicona, a two-inch-long, bloodsucking “kissing bug” that can carry the parasitical Chagas disease. Farther on, we found two ferocious-looking arañas lobo (wolf spiders), whose bite is said to cause painful swelling.

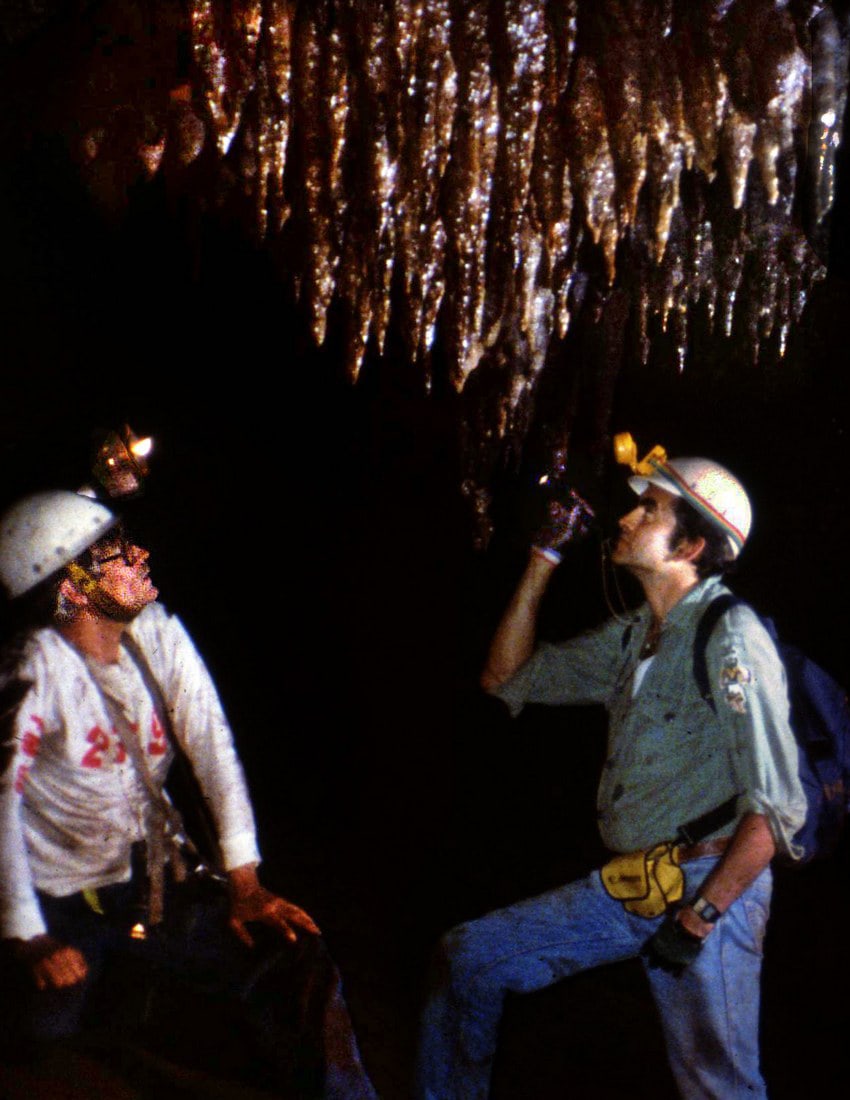

Leaving behind this delightful menagerie, we returned to the main passage, which led us to several rooms bristling with countless, shimmering brown stalactites. Many of these were within arm’s reach, and we were amazed not to find any of them broken.

Not far along, we gazed up at a balcony that was obviously home to a good-sized colony of bats. The next rooms we came to were either filled with breakdown or great heaps of sand.

In one place, we found deposits of fine black dust that we proved — with the help of a magnet — to be powdered iron, probably washed into the cave from the aerial tramway.

After 300 meters or so, we stood at the opening to a very large room filled with lots of chunky breakdown. We both stopped and looked at each other: “Do you hear what I hear?”

The sound reaching our ears was so much like the voices of people laughing, shouting and playing in a swimming pool that we really expected to find a balneario (water spa) at the other end of the room.

We actually set out looking for these people, whom we named The Water Sprites, but what we found were two streams of water on both sides of the room, each heading off in the opposite direction, apparently fed by a spring rising up from beneath the breakdown.

Were our “voices” generated by the gurgling stream on the right, or were they real voices floating into the cave above the wider “river” heading off to the left? We still don’t know.

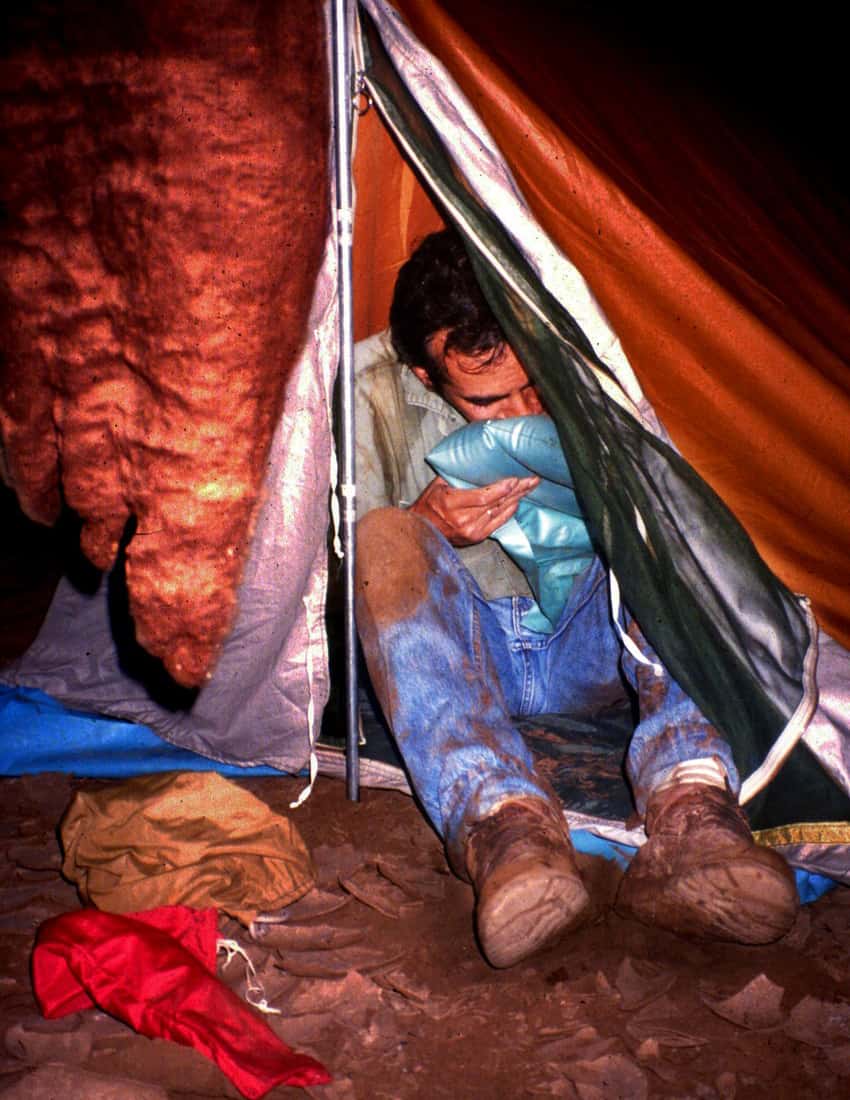

As we hadn’t come prepared for water sports and the hour was late, we headed back to the entrance area, which unlike the terrain outside the cave, was nice and flat. So we decided to pitch our tents here inside by tying them to a couple of conveniently located stalactites on the low ceiling.

Tents inside a cave? With vampire bats fluttering by at regular intervals (not to mention the other critters we had seen), we figured it would be a good idea.

Luis Rojas, who had been suffering from insomnia for weeks, finally got a good sleep, which was suddenly interrupted in what I thought was the middle of the night …

“ANYBODY IN THERE????” came a loud voice booming through the cave. Who in the world could that be?

We prudently declined to respond and a minute later heard “the voice” again, this time right outside our tents: “Here I am for my tour … let’s go!”

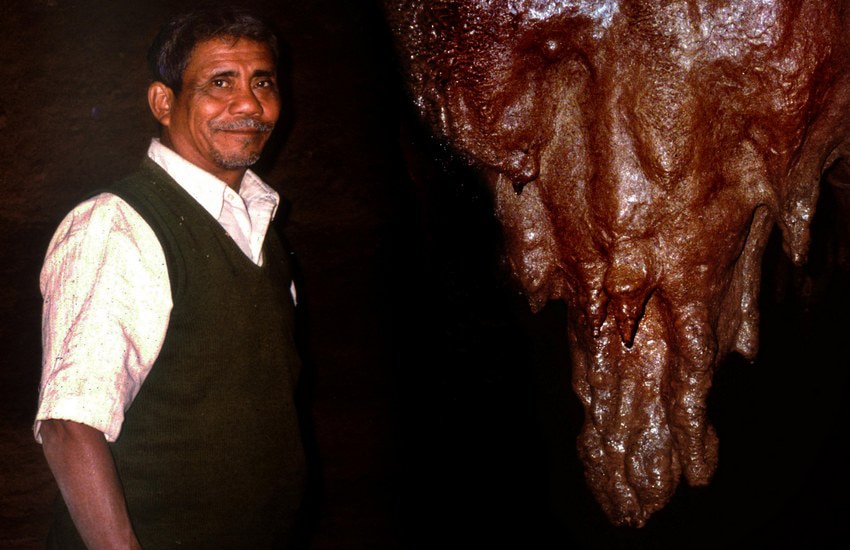

The voice was Don Rafa’s. I reached for my flashlight and looked at my watch. It was 6:30 a.m.!

Nevertheless, here was Don Rafael, smiling at us and opening a big thermos full of hot té de canela (cinnamon tea).

After the tour, as we tromped back up the steep slope, Don Rafa regaled us with tales of other caves in the area: La Cueva del Salitre, where we could see trout swimming about inside, and La Cueva de los Tindarapos, home to tailless whip scorpions (Amblypygi) — huge arachnids with mantis-like claws.

We had found it: a caver’s paradise!

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.