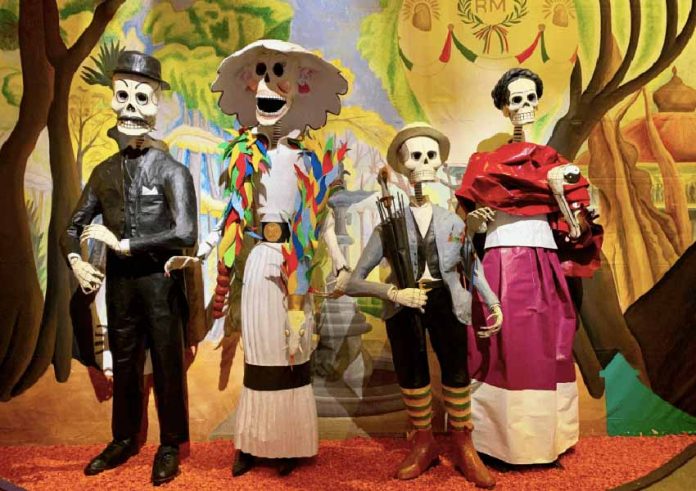

In the opening scenes of the James Bond film Spectre (2015), giant skeleton puppets parade down Mexico City streets, and Bond himself wears a skull mask with very regal clothing.

The parade was fictitious at the time, but its focus on depictions of skeletons (calacas) and skulls (calaveras) had basis in reality. Skeletons that imitate those of us of flesh and blood have been a part of Day of the Dead for some time.

One other positive nod for Bond: the puppets and masks were made of papier mache, a Mexico City tradition, and the skeletons were created by a local folk art cooperative, La Última Hora.

Calacas are not only central to Day of the Dead, they have become central to Mexican identity both inside and outside the country. Skeletons and other depictions of death date back to way before the arrival of the Spanish.

Missionaries tried to stamp out Mesoamerican beliefs about death, or at least co-opt them into Catholicism, but they were never completely successful. Instead, imagery and meanings keep evolving along with Mexican society.

Calacas today tend to represent one or more of three things: the fleeting nature of life; an acknowledgement of the reality of death by the living; or a reinforcement of Mexican identity, especially as it relates to the past.

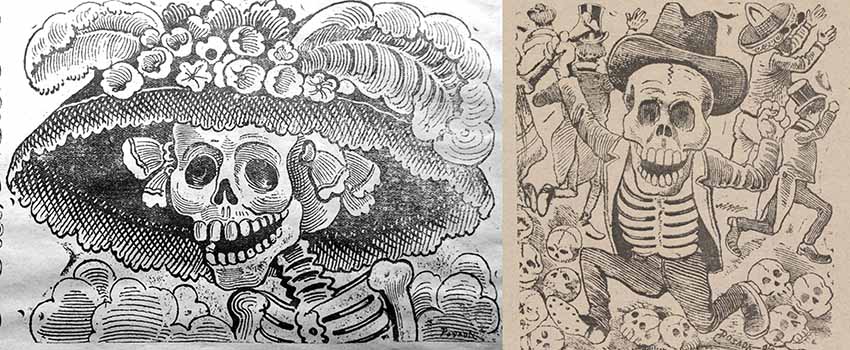

These modern interpretations have their origin with the work of political cartoonist José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913). He created a myriad of clothed and active calacas reflecting the social and political reality of pre-Revolution Mexico. The most famous of these is La Catrina.

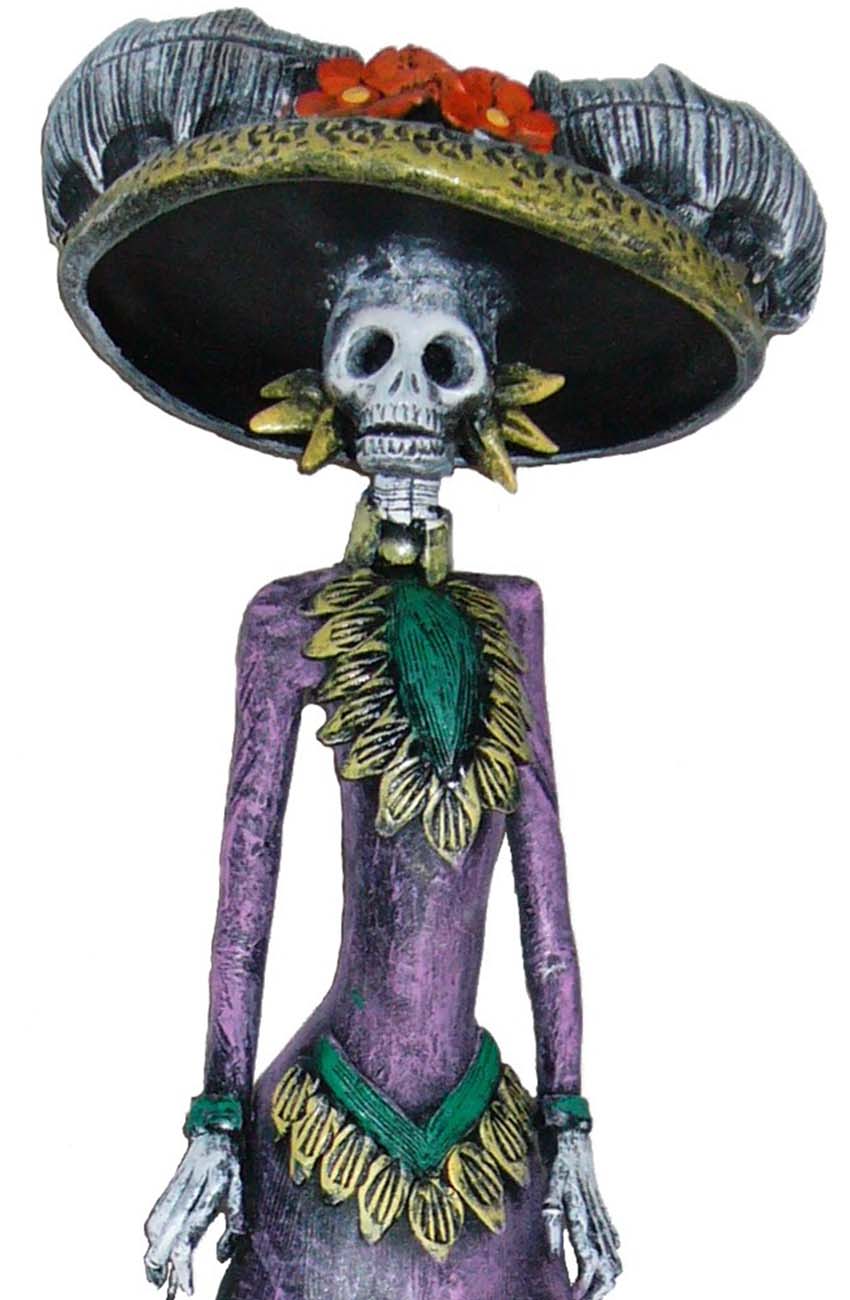

That was not his name for her. The original drawing was a skull wearing an ornate floral hat popular with late 19th-century upper-class women. They, and other European-style trappings, were also popular among mestizo and indigenous merchants who sold the fine ladies chickpeas and other “distinguishing” foodstuffs. Posada named his calaca figure La Garbancera (Chickpea Seller), and it was his criticism of women who denied their own heritage for financial gain.

It is more accurate to say that the La Catrina we know today is the creation of both Posada and Diego Rivera. Posada died in obscurity, but post-Revolution cultural authorities saw in his work an antecedent for the values they looked to promote. The name La Catrina first appears in a 1930 book about Posada, which Rivera was involved with. But the artist’s main contribution came through the 1948 mural Dream of a Sunday afternoon in Alameda Park.

Here, La Catrina not only has a body, a dress and a feather boa, she is surrounded by many past and contemporary Mexican notables, including Rivera himself as a child holding the calaca’s hand. The symbolism here is clear: death comes for everyone, no matter the social status.

Nowadays, La Catrina is so iconic, she is not really considered to be a calaca. She is classed separately, accompanied only by a “mate,” El Catrín, a dandy skeleton in clothes from the same time period.

So what about all the other calacas? Most have a more modern appearance, show doing both traditional and modern activities. Not so much has been written about them, but full disclosure, I did dive into the subject for my book “Mexican cartonería: Paper, paste and fiesta.”

For the status they enjoy today, if not their outright creation, modern calacas should absolutely be credited to Mexico City papier mache artisan and maestro, Pedro Linares (1906–1992), best known for his colorful monsters called alebrijes, but he has not received the credit he deserves for his calacas.

Papier mache artisans traditionally make festival paraphernalia. Piñatas are the best-known, but in central Mexico, they make much more than that.

The most traditional work for Day of the Dead is a skeleton assembled from a paper skull and bones, joined together with cords so that the figure can dangle in the air.

Skeletal figures appear in the opening scenes of the classic movie Macario (1960), but some are static and have sombreros and musical instruments. There is nothing in the credits, but both experts and the Linares family agree that the work is clearly by maestro Pedro.

Linares, who had contact with the artists and intellectuals of his day and was aware of the work of Posada and other iconic artists despite his very humble origins, took calacas from mere decoration to folk art, thanks to his artistic talent. As his fame grew from the 1950s on, he received increasingly-important commissions for calacas, and not just for Day of the Dead.

In 1968, he made 70 life-sized figures for the Mexico City Olympics, followed by La Muerte Tembloroso (The Tremoring Death), his depiction of the aftermath of the 1985 earthquake. His Atomic Apocalypse: Will Death Die? was made for England’s Museum of Mankind.

His work is why artisans today can make calacas year round but are busiest in the months before Day of the Dead.

Calacas and calaveras are made from just any material imaginable, from edibles (like sugar) to resin. They are still most frequently found on public and monumental altars for Day of the Dead.

One important subset of calacas are those which depict personages from Mexico’s past. Since the skeletons do not have faces, the person is identified through the calaca‘s clothing, pose and accessories.

These are very common on school and other government-sponsored altars, but perhaps the finest example is in Train of History, a project sponsored by the Mexico’s Museum of Popular Art for the country’s 2010 bicentennial. The work consists of boxcars, each with a scene from Mexico’s history. These include a depiction of Miguel Hidalgo’s patriotic Cry of Dolores speech, made from many different materials by artisans from different parts of Mexico. It was not created for Day of the Dead, but it is often exhibited at this time of the year.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.