Following the conquest of the Mexicas, Spanish chroniclers made an often unchallenged claim: that the Mexica emperor Moctezuma II mistook the conquistador Hernán Cortés for the serpent deity Quetzalcoatl. This, said chroniclers, helped Cortés prevail and colonize Mexico.

This story is just one chapter in the long historical narrative of divine status seemingly conferred upon flesh-and-blood individuals, from 16th-century Mexico to 20th-century Ethiopia.

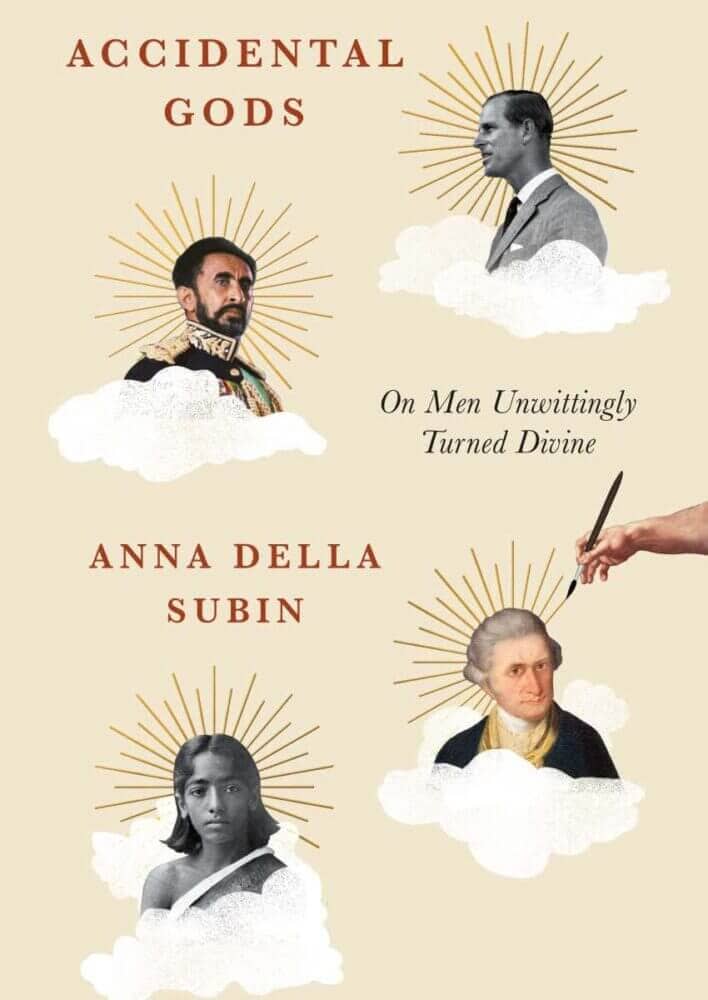

And yet, such accounts are invariably more complex than the way they are presented, says historian Anna Della Subin in her recently published book, Accidental Gods: On Men Unwittingly Turned Divine.

“An accidental god is a person who, without seeking it, has had divinity thrust upon them, through forces of accident, chance or coincidence, often against their will or their own intentions,” Subin explained.

She called the phenomenon “an archetype.”

“And once you start paying attention to the existence of this figure, you see him everywhere — accidental gods have appeared on nearly every continent on the map.”

They “are almost always men,” the historian said.

Subin’s book looks at the conquest of the Americas from diverse perspectives, using, among other reference sources, the Florentine Codex — a 1500s ethnographic study of civilizations in Mesoamerica organized by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún — Shakespeare’s The Tempest and a 1539 indigenous pageant of revenge against Cortés that took place in Tlaxcala, which Subin describes as a groundbreaking attempt at deicide.

The book addresses 15th- and 16th-century encounters between Europeans and indigenous peoples in the Americas dating back to Christopher Columbus and continuing into the narratives of Cortés in Mexico and conquistador Francisco Pizarro in Peru. In each of these cases, Spanish accounts held that indigenous peoples considered the new arrivals to be divine, facilitating conquest.

“Ever since the alleged dawn of the modern world, when Columbus landed on an unknown shore and was hailed as a ‘celestial being,’ the narrative that the peoples of the New World mistook Europeans for gods became a trope that served to legitimize the conquests,” Subin said.

For example, Moctezuma’s alleged belief that Cortés was Quetzalcoatl “was used to construct a narrative that the Mexica emperor had willingly given up his throne to the invaders because he thought the god was the rightful owner of his land,” she said.

“Or the [idea] that ‘natives’ thought Europeans were divine was used as proof that the conquests and Christian conversion were preordained — the natives had been waiting for the conquistadors to arrive and knew they had some special relationship to the true God.”

Her book describes such claims by the Spanish as “foundational myths of the colonization of the Americas,” which “ushered in a new century in which nearly 60 million inhabitants of the New World would be killed.”

As she writes, “That Moctezuma mistook the Spanish for gods became the primary explanation as to why an empire of millions had collapsed soon after the arrival of a small band of foreigners. Tales spread that the Mexica thought the horses were deities, the ships were temples, the guns were gods breathing fire.”

She notes a further complexity: West African slaves joined in the conquest, and according to the Florentine Codex, the Mexica considered them to be “soiled gods”. Yet, she writes, “any mention of ‘soiled gods,’ or deified African slaves, was erased from the story.”

Overall, when Subin examined the foundational myths of the Spanish Empire, she found more questions than answers — including about the “feathered serpent,” deity Quetzalcoatl. In the book, she writes that he was worshiped dating back to 400 B.C., yet calls him “never particularly prominent in Tenochtitlán.”

Meanwhile, the words that the Mexica supposedly called the newcomers — teules or teotl, first used by Cortés’ translator and concubine Malinche — were translated as dios (God) by the conquistadors. As Subin explained, these words actually referred to something extraordinary or powerful but not necessarily supernatural.

Subin found other similar instances of shaky translation of indigenous terms that allegedly described Columbus and Pizarro as divine beings.

“What I’m doing in the book is paying close attention to how and why these foundational myths of apotheosis were told,” Subin explained. “I peel back the layers of the stories — and especially the language itself — to interrogate the ways in which they were deployed to sanctify imperialism.”

The Spanish conquistadors are not the only “accidental gods” across history to which Subin has applied this approach. She also researched Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, who became a divinity in the Rastafarian religion founded in Jamaica.

“In a sort of strange epiphany, I thought, well, what happens if you have too much charismatic power? You might find yourself hailed as a god, like Haile Selassie in the religion of Rastafari,” she said. “I became obsessed with his story, how a man on one side of the earth, in Ethiopia, could become a god on the other side, in Jamaica, without ever consenting to it.”

She also explored the origin of the term “worship” itself — Old English for a “worthy ship” that ensures safe passage. She sees one accidental god as especially reflective of this phrase — England’s Prince Philip, who despite his numerous gaffes was worshiped by the people of the South Seas island of Tanna.

“For many of his critics, Philip, notorious for joking about Melanesian peoples as cannibals, might seem the least worthy of all,” Subin said. “But what interests me is how the deification of Prince Philip, strange as it might seem, actually became a profound means of empowerment and emancipation in Tanna just as the island was decolonizing from Britain rule.”

The book also explores how indigenous people have been reclaiming their gods from colonial narratives. As early as 1539, indigenous people in Tlaxcala staged a revenge pageant in which Hernán Cortés was depicted as a sultan commanding an infidel army defending Jerusalem from a Christian force. After the Christians triumphed, the fictional Cortés was spared in exchange for an on-stage baptism.

As for Quetzalcoatl, the Mesoamerican serpent god became incorporated into Latin American resistance movements.

“In Accidental Gods, I’m not seeking to reveal ‘what really happened’ in historic moments of apotheosis, such as when Moctezuma met Cortés,” Subin said. “I don’t think there can exist a single narrative, right or wrong, that stands to be corrected.

“Instead, I’m unraveling the way that these narratives have been woven together, edited, reworked and reproduced to create what successive generations have held as true.”

Her book is driven by curiosity about why so many stories of men turned divine exist, and what humanity’s gods reveal about the strange state of being human.

“Whether factual or mythical, deification has been a profound driving force in modern political history,” she said.

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.