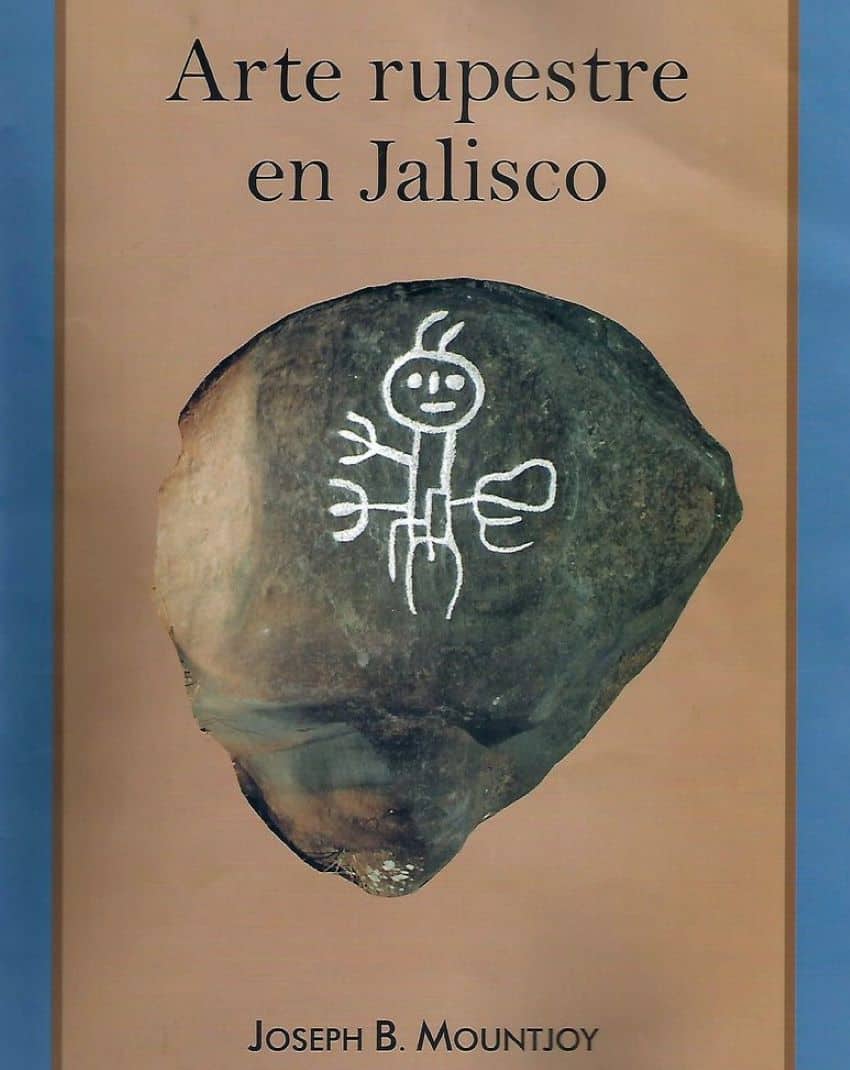

One day, I received in the mail a most interesting book entitled Arte Rupestre en Jalisco (Rock Art in Jalisco) by archaeologist Joseph B. Mountjoy. It had been kindly sent to me by the author himself after I asked him perhaps one too many questions about petroglyphs.

Joe suggested I might find many of the answers I sought in the pages of this richly illustrated, 48-page book (all in Spanish), and I certainly did.

If anyone ought to know rock art, it’s Dr. Mountjoy, who registered his first pintura rupestre (rock painting) back in 1964 and has analyzed some 20,000 glyphs since then.

To fully appreciate his insights, you really need to visit the first-class museum he has set up in the Casa de Cultura of Mascota (140 kilometers west of Guadalajara), where you will find a whole room dedicated to petroglyphs, a project carried out in collaboration with National Geographic magazine.

If you ask, the caretaker of the museum will even lend you a little guidebook to the place in English.

Mascota by the way, is a beautiful and fascinating little town well worth a visit even if petroglyphs are not your thing.

Between now and your trip to Mascota, here are a few insights on petroglyphs that I gleaned while reading Arte Rupestre en Jalisco:

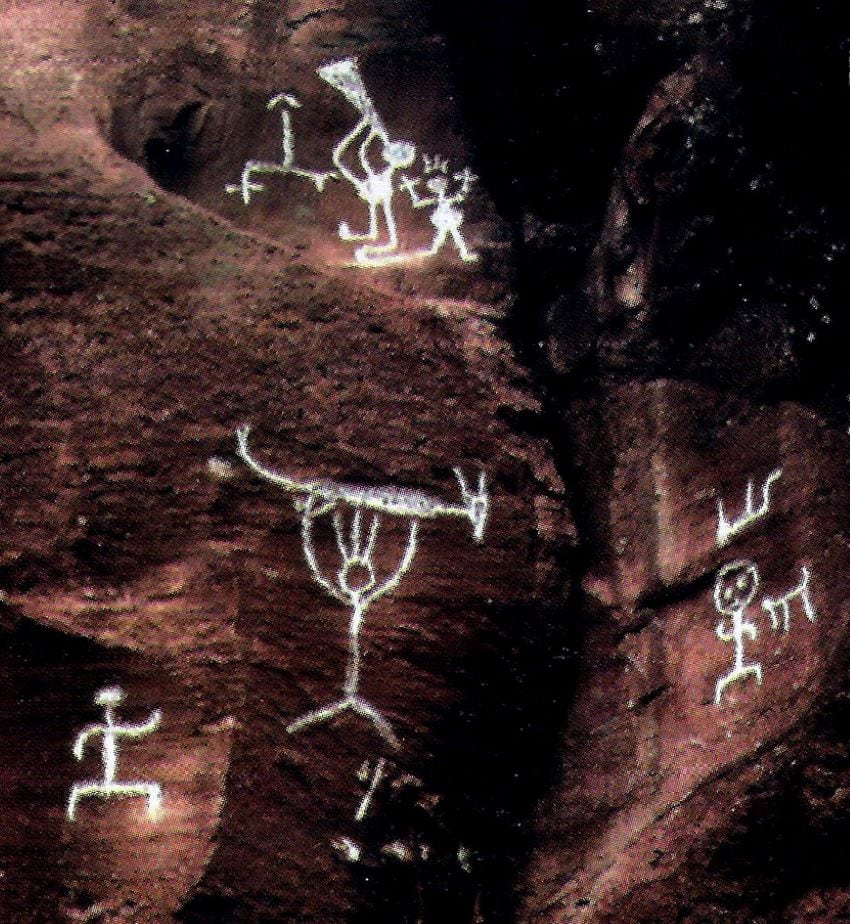

The great majority of rock-art designs, says Mountjoy, are related to ceremonies aimed at obtaining rain from the sun god for the benefit of those plants and animals that ancient peoples depended on for their sustenance.

The ceremonies had to do with that critical transition from the dry to the rainy season, and the drawings were destined for a god rather than for fellow human beings.

As for the meaning of most rock art, Mountjoy says, “Approximately 98% of the petroglyphs [in western Jalisco] can be explained by only three intimately related factors: sun, water and fertility.”

In respect to the age of most Jalisco petroglyphs, the great majority were made during the Postclassic Period (900 to 1500 AD), although a few may go back to the time of Christ.

What are these interpretations based on? “In Jalisco, the main source of ethnographic information for interpreting rock art is the Huichol culture,” says Mountjoy. “They have preserved their culture, customs and beliefs quite well,” he points out, adding that the religious symbolism of the Huicholes was the subject of an extensive study carried out in the 19th century by ethnographer Carl Lumholtz.

Many of the rock-art designs we see could be interpreted as the physical manifestations of prayers offered up to the sun god to obtain some practical benefit. As the walls of some Catholic shrines are filled with milagritos, testimonials giving thanks for favors received from on high, many ancient petroglyphs were chiseled in rock begging for such celestial favors.

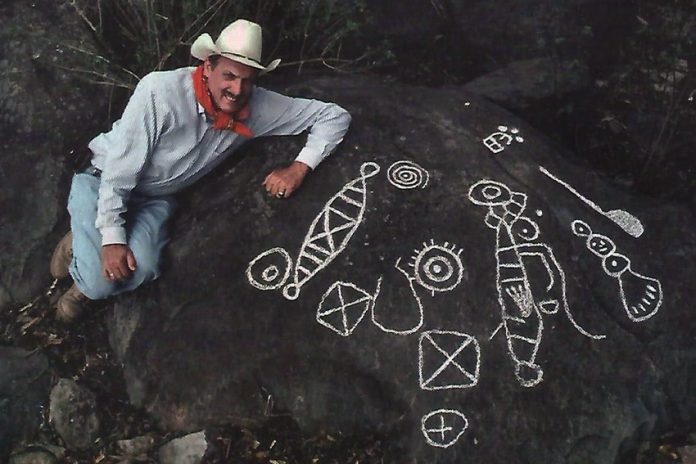

Perusing the book’s many color photos of rock art, I learned that the symbol for the sun god is often a set of concentric circles, sometimes surrounded by rays, but it can also be as simple as an unadorned pit carved in the rock.

The more elaborate designs can also have arms, legs and a tail, representing either the god in anthropomorphic form or a shaman who carries out rites supplicating the sun god.

As for that other commonly seen symbol, the spiral, Mountjoy says it is “the physical manifestation of a ceremony during which the Sun God was entreated to send rain.”

Since many petroglyphs are a prayer for water, it’s not surprising he’s found them to be most abundant in areas where rivers and pools typically dry up during the course of the dry season.

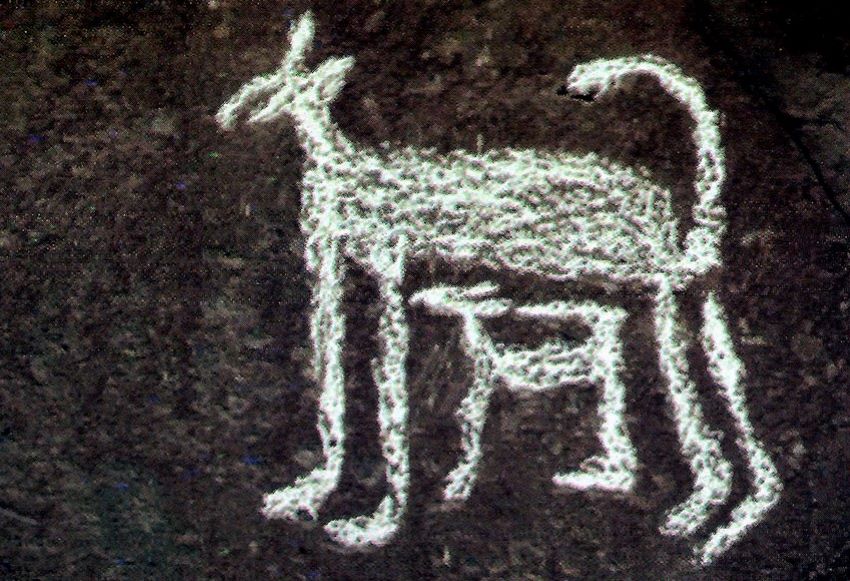

One of the most commonly depicted animals in west Mexican petroglyphs is the deer.

In Ocotillo Canyon near Mascota, Mountjoy found hundreds of petroglyphs representing an important ceremony that is still practiced today among the Wixárika (Huichol) people: the Sacred Deer Hunt.

The original purpose of the Sacred Hunt in ancient times was not to kill or eat deer but to catch them alive, tie their legs together, carry them to a ceremonial site and finally to prick their ears in order to obtain a few drops of their blood.

“In Huichol mythology,” says Mountjoy,” this hunt was ordered by the gods Father Sun and Uncle Fire for the purpose of anointing ritual objects with deer blood,” says Mountjoy. “It was the last stage of the pilgrimage to obtain peyote in order to make sure the sun keeps shining …

“The deer’s blood was also essential for the toasted corn ceremony, the last ritual of the dry season. So it can be seen clearly how the Huicholes related sun, water and fertility with deer, peyote and corn.”

The Sacred Deer Hunt took place somewhere between January and March and may have lasted as long as a month. According to ethnographer Robert Zingg, the hunters had to come back with the number of deer specified by their shaman in his dreams.

During the hunt, the shaman would call the deer with the help of a megaphone made of tree bark. Dogs would be used to drive the deer into a narrow canyon, where they would then be trapped in nets and carried off.

These elements of the Sacred Deer Hunt can be seen again and again in Mountjoy’s photos of rock art in Mascota’s Ocotillo Canyon.

A fascinating section of the book is dedicated to a kind of rock engraving called the patole. This is the ancient equivalent of board games like backgammon or snakes and ladders.

The “board” was engraved on a flat, horizontal rock, and for dice, the Aztecs used big beans painted with white dots and known as patoles.

The oldest patole petroglyphs go back to 300 A.D. and are found in places like Teotihuacán and Palenque. There was an elaborate kind of patole shaped like a rectangle with a cross in it with 52 spaces where your token could land (representing the Mesoamerican century).

A great many of these were recently unearthed at La Presa de la Luz near Arandas, Jalisco.

As proof that the ancients were board game fans, “abbreviated patoles” have also been found with only 12 spaces.

Mountjoy encountered both styles in the Mascota area.

“I should mention,” he says, “that for the Aztecs, playing patole also included drinking alcoholic beverages and gambling for high stakes.”

At the end of the book, we are reminded that most petroglyphs were considered sacred by their makers and that visiting sites with rock art should be considered like stepping into a temple or a church.

Damaging petroglyphs or making fires near them (which can cause the rock to fragment) would be very offensive to native peoples.

Arte Rupestre en Jalisco is a thin, magazine-sized (27 by 21.5cm), 48-page paperback with 44 photos, almost all in color, beautifully printed by Acento Editores of Guadalajara.

The price is 150 pesos and — for the moment — it is for sale exclusively at the Casa Cultural in Mascota. You can also download the PDF version (4.47 megabytes) free from my website.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.