Over the weekend, the plaza in front of San Pedro Cholula’s pyramid, Tlachihualtepetl, was given over to the Ancestral Alliance festival, featuring traditional pre-Hispanic ceremonies, workshops and talks by elders well-versed in ancient traditions.

“This event is about 25 years old,” said Ocelocozcatl Xiutletl, the founder and co-coordinator. “It is to show indigenous culture, our food, crafts and ceremonies. We want to show people the real thing, to hear from the elders about our culture.”

Seven different nations were represented, he said.

On the first day, an opening ceremony — “to give thanks for the food we have,” explained Yao Copaltzin, the festival’s other co-coordinator — was held alongside an ancient design called Nahui Ollin — Náhuatl for “four movements” or “the fourth course of the sun.”

The design, which appears in Mexica codices, has an elliptical shape that signifies continuity, Flavio Huerta Villegas said. Of the ceremony, he said, “It is an offering of seeds, flowers and fruit.”

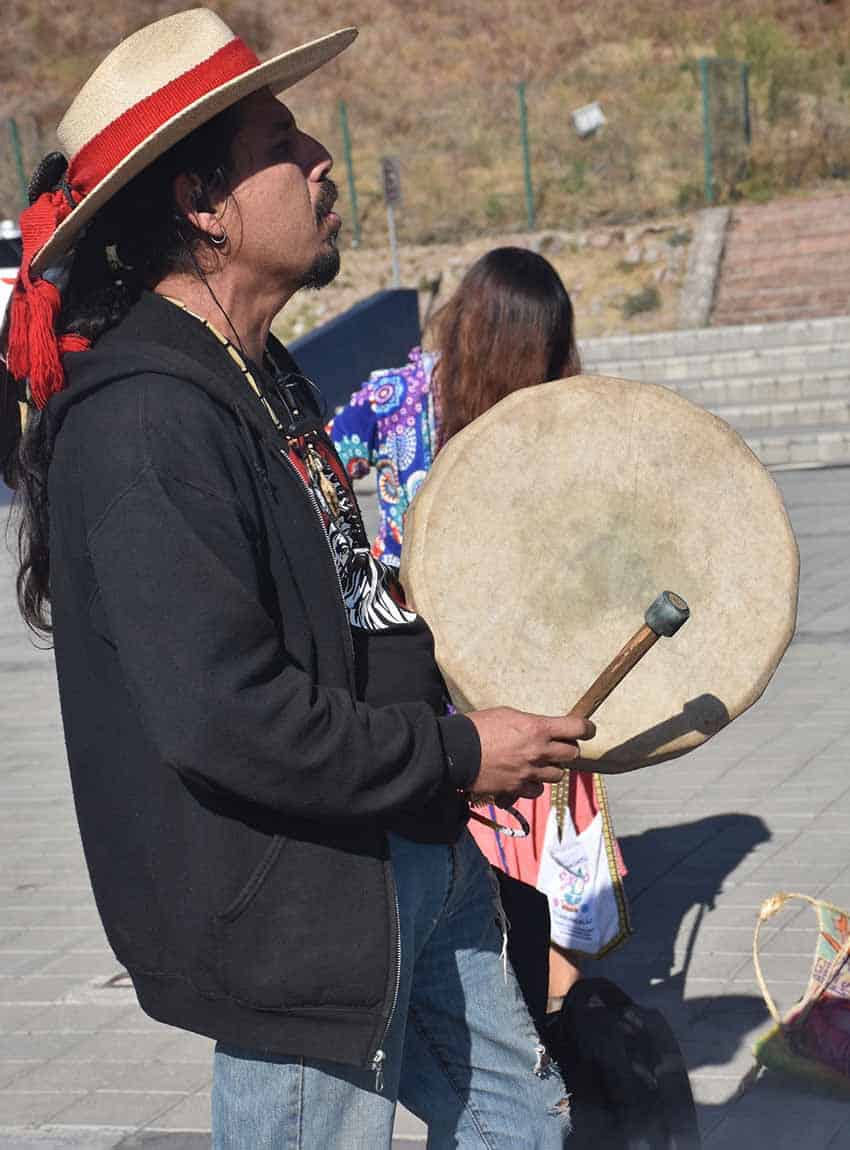

During the ceremony, Xiutletl chanted and played a hand-held frame drum while the air filled with the sound of conch shells and smoke from burning incense.

Each day of the festival, traditional music groups like Cuetzalan Folk and the more esoteric Huitzilin gave concerts.

“It’s medicine music,” said singer and guitarist Luis Salazar, who said he also conducts traditional medicine ceremonies. “In our songs, we mention different elements of nature; we work with animals and sacred plants.”

At Daniel Contreras Nateras’s Quetzalcóatl wind ceremony, participants got to select from a variety of wind instruments and blow into them while Contreras played a frame drum. “The instruments represent the wind, and the wind is Quetzalcóatl,” he said.

Abuela (a title of respect) Teresa Contreras González, a curandera (healer), led one of the festival’s many workshops. Hers was called “Adjustment with Rebozo.”

Rebozo is a sacred cloth women use when carrying or feeding their babies, she explained. Here, she used it for healing.

As a demonstration, she slipped the rebozo under parts of my body, yanked me up, tugged on my extremities and gave me an intense massage. Instantly, the soreness I’d had that day from a strenuous hike disappeared.

Local artist Erika Wong’s workshop was on mandalas, which she learned to make from the Huichol community in Nayarit.

“It is a star with eight points,” she said, “a symbol of fullness and regeneration. It is the oldest symbol to represent the Mother God. It is used to protect the waters, harvests and [against] bad influences.”

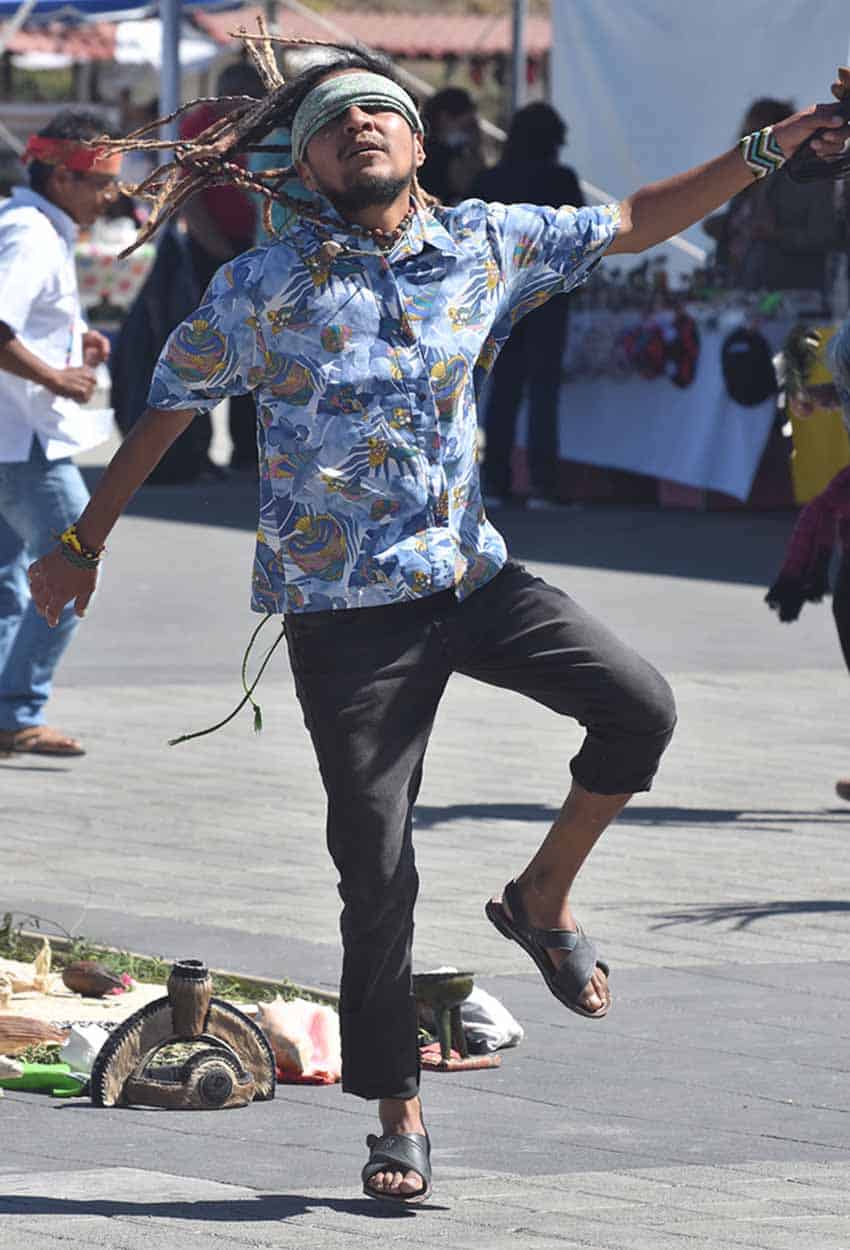

About 100 different vendors sold crafts, food, mezcal, cacao, jewelry and more during the weekend. Participants joined in pre-Hispanic dances continuing long into the night, underwent cleansing ceremonies or tried a temazcal, a traditional sweat lodge.

The festival takes place in a different location every year.

“Next year, maybe it will be in Michoacan,” said Xiutletl. “Maybe Chile.”

Xiutletl and Copaltzin run the Pahkalli-Xerip Center in Nealtican, Puebla, which offers traditional ceremonies and therapies and the information center for the festival. To contact them or any of the festival’s presenters, go to the Pahkalli-Xerip Center website or contact the the duo by email or call at +52 222 325 0895.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.