A few years ago the story broke.

“¡Lo encontraron!” ran the headlines. They found it! They found Guadalajara’s legendary lost bridge, el Puente de las Damas (the Ladies’ Bridge). There really was such a thing, and at last we know where it is!

This, I thought, was an interesting piece of news, but to me, it seemed a mere nothing in comparison with the much bigger story: that the city had managed to lose the bridge in the first place.

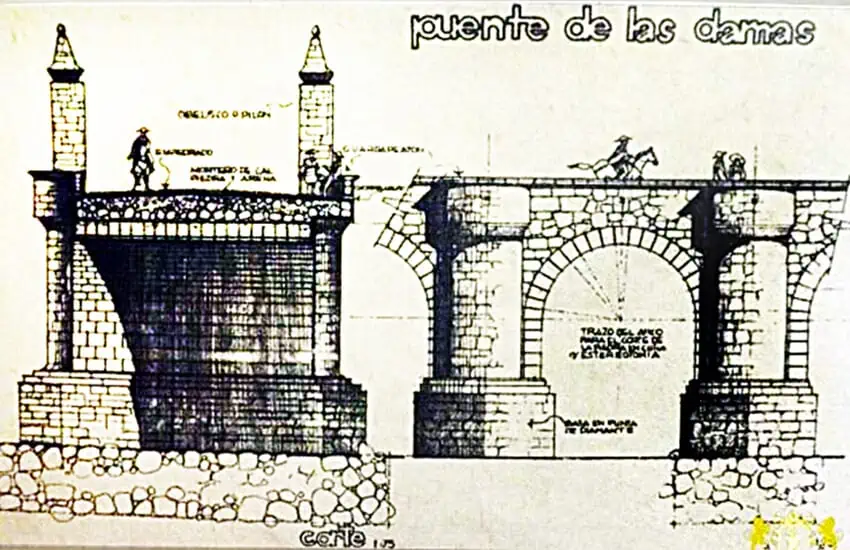

“What?” I exclaimed, “a hundred years ago, Guadalajara lost a bridge 50 meters long 12 meters wide and 15 meters high?”

From the moment I heard the story, I was determined to visit the Ladies’ Bridge in the hope that seeing it up close would reveal how in the world they had managed to lose track of a structure weighing countless tons.

On March 24, 2022, city officials formally inaugurated a kind of underground and “under-bridge” museum that had been created — at a cost of 6 million pesos — in space that had been hollowed out beneath the elegant arches of the long-lost bridge.

You can visit this unique museum free of charge from Tuesday to Sunday.

“Let’s go!” I told my friends. “We need to learn the curious story of this bridge.”

The museum entrance is at the corner of La Paz and Colón in downtown Guadalajara.

At street level, all you can see are a number of skylights poking out of the sidewalk and a doorway to a small reception room where a maximum of 15 people wait their turn to descend a narrow stairway leading to who-knows-where.

“You will be stooping through low passageways where you could bang your head,” said the guide, “so you may want to wear one of these optional helmets.”

Once helmeted and ready for action, we descended the stairs and passed through a low slot that had been punched through a very thick stone wall, and there we were, gathered inside arch No. 1 of Puente de las Damas.

Guadalajara of the late 1700s was inhabited by mestizos and Spaniards, we learned. To the south, the town ended at a river running through a gully known as el Arroyo del Arenal. On the other side of the gully lived the indigenous people in their own town, appropriately called Mexicalzingo, which means “the place inhabited by the honorable Mexicans.”

Many people were ultra-pious in those days, and the ladies of lineage had the custom of crossing the river every Friday to go visit a celebrated crucifix ensconced in the church of Saint John the Baptist on the other side.

The crucifix was known as The Lord of Penance because once upon a time, teachers used to send their disobedient students to say their penance while kneeling in front of it.

This cross was a cornstalk-paste sculpture, conveniently light for processions, but when it became old and moth-eaten, it was sent to a convent for restoration. Here it supposedly cured a paralyzed nun and suddenly gained a reputation for working miracles.

To visit the miraculous crucifix, the ladies of Guadalajara faced two problems. Number one was a flooded river: every once in a while, during the rainy season, water would pour down from Colli Volcano (at the edge of what is now the Primavera Forest) and flood Arroyo del Arenal. The water level would rise so high that no one could wade across it.

Not only was it impossible for the ladies to visit the church, it was equally impossible for the indigenous people to come to work in the ladies’ homes as servants and laborers.

Problem No. 2 had to do with elegance: the visit to the church was an opportunity for the well-off ladies to display the latest fashions both to one another and also to the folks on the other side of the river, who, in those days before television, probably considered the weekly arrival of the damas as quite an event.

No one looks elegant while wading through water, and, far worse, even the most modest dama was obliged to lift her skirts while hopping from rock to rock, a scandalous situation if there ever was one.

Frustrated, the ladies of Guadalajara appealed to the most important man in town: Fray Antonio Alcalde.

Now Fray Alcalde had managed to get a hospital for Guadalajara as well as its first printing press and had founded the Universidad de Guadalajara on top of that, so how about a beautiful, spacious bridge across which the ladies could sashay in all their finery?

With the help and approval of the venerable friar, who was now in his last years, the ladies succeeded in collecting the necessary funds, and around 1791, the construction of the bridge was begun.

Today, this is considered Guadalajara’s first collaborative public work, as it was created by and for the people.

Somewhere around 1798, they finished the job. It was one huge, solid bridge built of volcanic rock, so solid that one would believe it should still be doing its job today, continuing to provide a means for people — both elegant and humble — to cross Arroyo del Arenal.

The bridge did, in fact, provide this service for a full 100 years, but things had slowly changed over the years. The Arenal was no longer flooding, and the river that it flowed into, the Río de San Juan, had become black and smelly.

“So,” explained our guide, “in the early 1900s, they replaced the San Juan River with a sewage pipe.”

Suddenly it became clear to me why and how that huge stone bridge had disappeared. The Arroyo Arenal was now a long, dry depression running east and west, and the San Juan was another dry depression running north and south — straight through the most expensive real estate in downtown Guadalajara.

So in 1930, they filled both of these old riverbeds with rubble and created two long strips of very valuable land smack in the heart of the city. Someone surely made a fortune selling lots, and with the passage of time, everyone forgot about the now useless bridge buried four meters beneath Avenida de la Paz.

Was there a referendum 100 years ago asking, “Would you like to preserve this historical old bridge?” I very much doubt it.

So that is how you can lose a 50-meter-long bridge. As for finding it again, the Ministry of Public Works (SIOP) claims credit: they say they were renovating Calle Colón in 2016, and when they stripped away the old bed of asphalt, there it was: a legend transformed into a reality.

But not so fast. There just happens to be a book — out of print, of course — about the Ladies’ Bridge (El Arroyo Del Arenal by José Trinidad González Gutiérrez). The author says that the bridge was rediscovered by one Roberto Rivera Sandoval back on March 30, 1994.

A neighbor of Rivera’s, it seems, had been cleaning up an empty lot on Avenida Colón and had found a hole whose bottom could not be seen. The two of them built a homemade ladder on the spot, and — armed with a rope, a flashlight and a camera — Rivera climbed down four meters to the floor of a pitch-black tunnel oriented east and west.

Down the center of the tunnel ran a canal filled with aguas negras (sewage). Rivera followed the tunnel until it curved, and here he came upon a stone structure which he soon realized was actually an old bridge.

Rivera reported his find to the director of the City Museum, and three days later wriggled back into the tunnel to measure the bridge’s length.

So it seems that the Puente de las Damas has been rediscovered multiple times, and now, thanks to the creation of the Underground Museum, you, too, can rediscover it for yourself — from 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. any day of the week but Monday.

To find the door leading down to the buried bridge, just ask Google Maps to take you to Puente de las Damas, Calle Colón, Mexicaltzingo, Guadalajara, Jalisco.

During the hot months of summer, it’s a cool place to visit — almost as cool as a cave!

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.