Last year, Mexico News Daily published a primer about Mexico’s War of Independence for the upcoming holidays. This year, we focus on Mexico’s independence hero, Miguel Hidalgo.

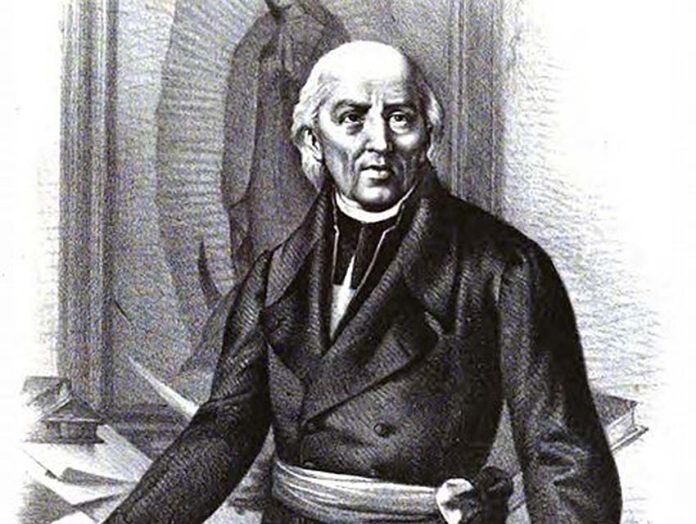

“Father of the country” is not a concept unique to the United States. Many countries have figures honored with that title, and in Mexico, that man is Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla.

For those of us raised to revere George Washington as a near-saint, it’s perhaps curious that Hidalgo is remembered not only as the father of his country but also a Catholic priest — and despite the latter detail, the father of two daughters.

Born in Guanajuato in 1753, Hidalgo was a criollo, a person of Spanish heritage born in New Spain. They were the second highest-ranking caste in New Spain, under peninsulares, those born in the mother country. This class system was significant to both Hidalgo’s life and Mexico’s War of Independence.

Mexico’s “founding father” attended school in Valladolid (today Morelia, Michoacán) and Mexico City. He was ordained as a Catholic priest in 1778. Some sources emphasize that Hidalgo was not a particularly pious priest, in it more for the position and economic gain, but that was not uncommon during the time period.

In 1803, he landed the position of parish priest in Dolores, in the state of Guanajuato; it was a wealthy community. Aside from his salary, he earned money through various businesses, including the raising of olives and grapes, which were both banned in the colonies by the Spanish crown so as not to compete with Spain’s imports.

Charismatic and intelligent, Hidalgo had good relationships with people in all of New Spain’s castes, including the mestizos (mixed-race) and the indigenous. However, some of his behavior, like having mistresses, got him in hot water with his superiors. He was also influenced by Enlightenment values and other then-radical ideas which led him to work for the economic betterment of the poor. This did not often sit well with hacienda owners.

Hidalgo’s independence career began in literature-reading circles — a popular pastime for criollos. These literature circles were not only social but political. They provided cover for those sharing banned news and ideas. A pivotal moment came when Spain was invaded by Napoleon in 1808, installing his brother onto the Spanish throne.

As Spaniards, the criollos of Mexico could not accept the usurper, but as “Mexicans” they saw an opportunity in Spain’s chaos and weakness. Also a factor: the new French-installed government in Spain began to economically squeeze the colonies, to the detriment of both criollos and the lower classes.

The first revolts against Spain’s control of Mexico were quickly put down, but this did not settle anything. Although he’d been active in rebel circles beforehand, Hidalgo’s main shift towards independence came through a group known as the Querétaro Conspiracy.

The group planned to start the revolt in December 1810, but before the time came, they realized that they had been exposed. Rather than run, Hidalgo decided simply to push the start date up two months.

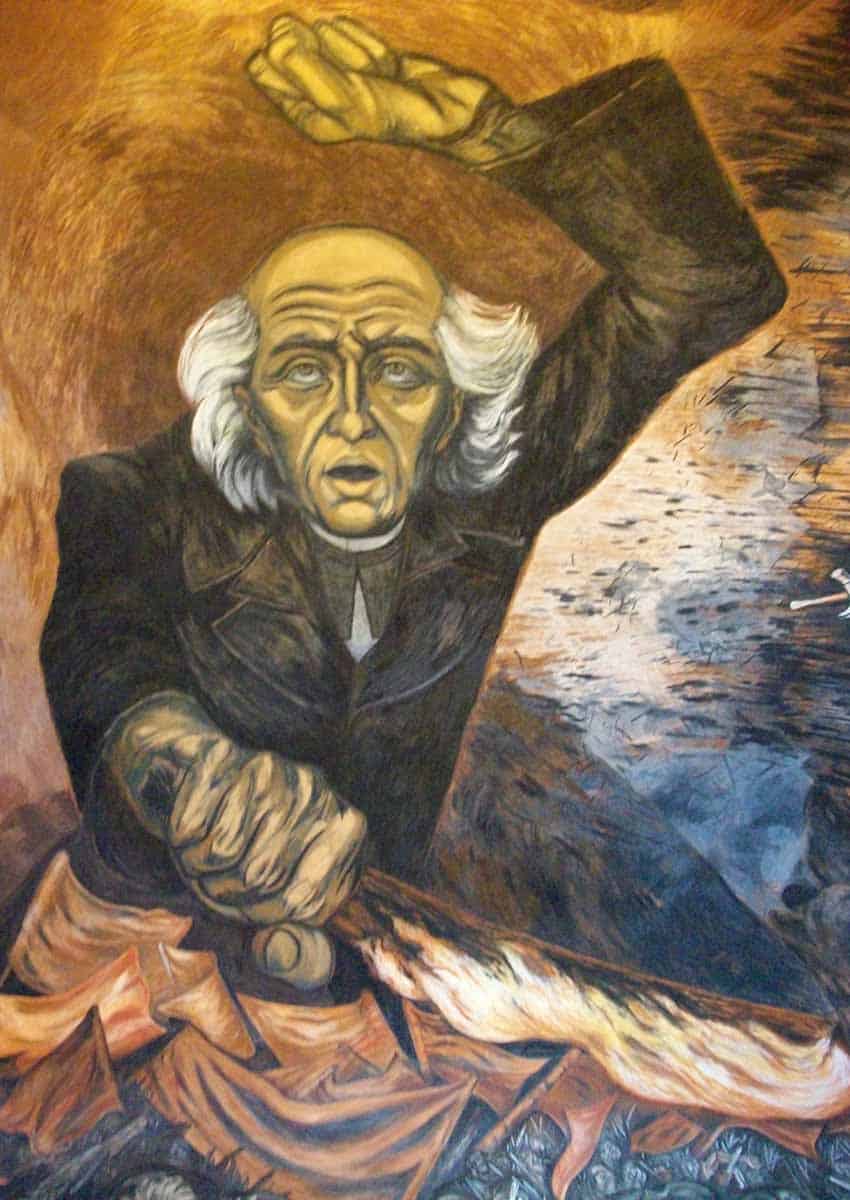

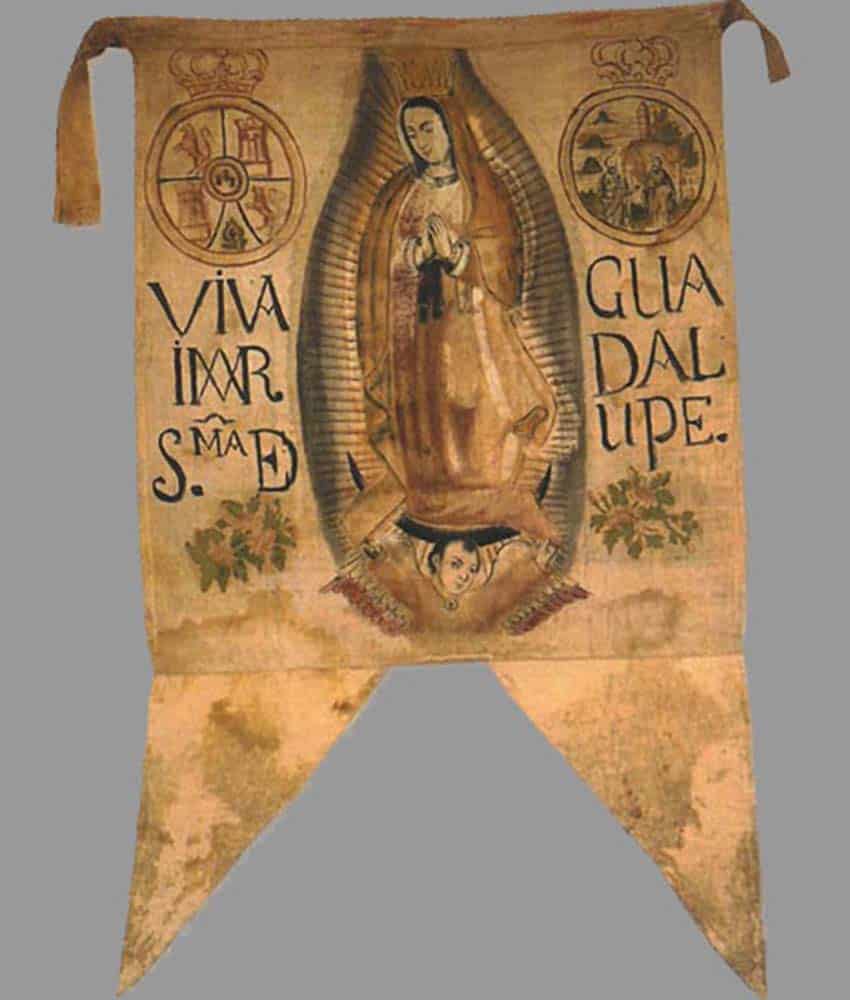

His first move was to ring the bell on the Dolores parish church to convene the locals. With a speech that is now known as the Cry of Dolores (El Grito de Dolores), he urged the mestizos and indigenous to “free themselves” from the “hated Spaniards” under the banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe, who was already a Catholic symbol of Mexico, said to have appeared in visions to an indigenous man here in 1531.

Hidalgo’s social status and charisma brought several hundred recruits to serve under his command with Ignacio Allende, a professional soldier who would be remembered as another Independence hero. Really a mob, this “army” marched on cities in Guanajuato, starting with San Miguel el Grande (now San Miguel de Allende), plundering and gathering more recruits by the thousands.

On September 28, Hidalgo took the city of Guanajuato, with the mestizos and indigenous taking vengeance on the city’s elite. Hidalgo did little to stop them despite being a priest, and both he and Allende were quickly excommunicated as a result.

Hidalgo’s army took Valladolid (i.e. Morelia) on October 17 and Toluca (today in México state) on October 25.

On October 30, Hidalgo was outside of Mexico City, where a royal regiment was sent to confront the rebellion. At the ensuing Battle of Monte de las Cruces, Hidalgo and Allende won, but it was bloody. What happened next is something of a mystery.

Allende urged Hidalgo to press on to Mexico City, but Hidalgo decided to retreat. There is no documentation as to why.

One story states that Hidalgo was upset over the carnage. Another says that he received false information that royalist forces in the capital were far stronger than they really were.

History records the retreat as a catastrophic mistake. Recruits began to desert and the royalists were in pursuit. Hidalgo managed to get to Guadalajara in November 1810, where he was greeted as a liberator, but the rebels were attacked again, forcing Hidalgo and Allende northward to look for help from the United States. However, both were captured in Coahuila on May 21, 1811.

Hidalgo was executed by firing squad on July 30, 1811, supposedly putting his hand over his heart to indicate to the soldiers where to aim. His body was beheaded and the head sent to Guanajuato city to be displayed there as a warning. It did not work. The reins that fell from Hidalgo’s hands were taken up by José María Morelos.

One possible lesson from Hidalgo’s story might be not to believe your own hype. His charisma and initial successes made him impervious to questioning. He would not listen to Allende, although the latter had the needed military knowledge.

If Hidalgo had decided to attack Mexico City, it is very possible that the War of Independence would have ended then, but it is doubtful that it would have ended the bloodshed.

First of all, there is no indication that Hidalgo would have made a better head of state than he did a general. The coups and civil wars of 19th-century Mexico just would have started 10 years sooner.

What Hidalgo provides is an inspiring figure and story on which to hang the concept of Mexican independence. This is evident with the reenactment of the Cry of Dolores each year at 11 p.m. on September 15, done by every ranking politician in the country, including the president, whose Grito is broadcast on national television.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.