So what’s up with “Japanese peanuts” in Mexico that are in every convenience store in the snack aisle? The peanuts are not grown in Japan, nor is the snack imported from there. But there is a Japanese connection.

And that connection’s name is Yashigei Nakatani Moriguchi.

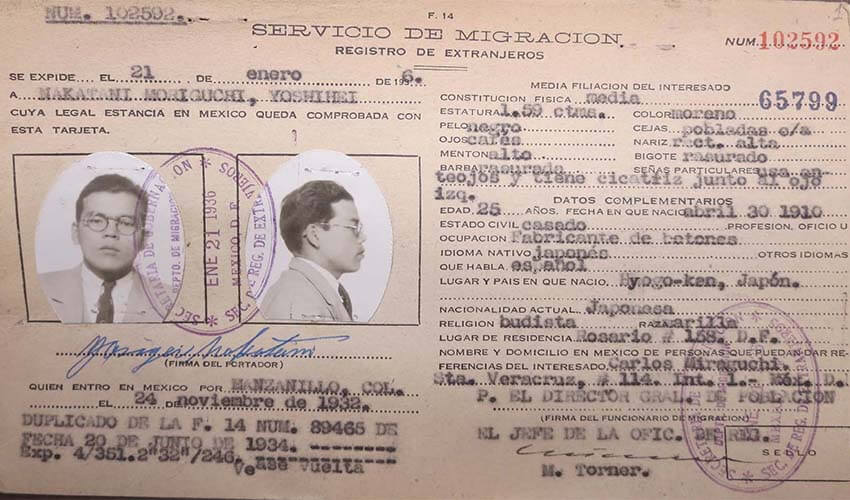

Mexico has had Japanese immigration since the late 19th century, when the government allowed immigrants from there to work on railroads and commercial farms. But by the time Nakatani arrived in 1932, such immigration required sponsorship by a Mexican resident.

So Nakatani obtained his Mexican visa by answering a job ad in Japan for a company that owned a button factory in Mexico, as well as the “El Nuevo Japón” department store, a competitor to the upscale Liverpool and El Palacio de Hierro. Nakatani’s plan was to work in Mexico for five years making buttons and then return home.

In his memoir, Ese Árbol aún Sigue en Pie (This Tree is Still Standing), Nakatani describes the day he stepped off the boat in Manzanillo, Colima, in 1932 — in particular the immediate culture shock and disappointment in seeing poverty in the streets. But he had a solid job waiting for him in Mexico City.

In the nation’s capital, he dealt with discrimination and the complete inability to speak Spanish. However, this did not keep him from renting a room from a woman who would become his mother-in-law.

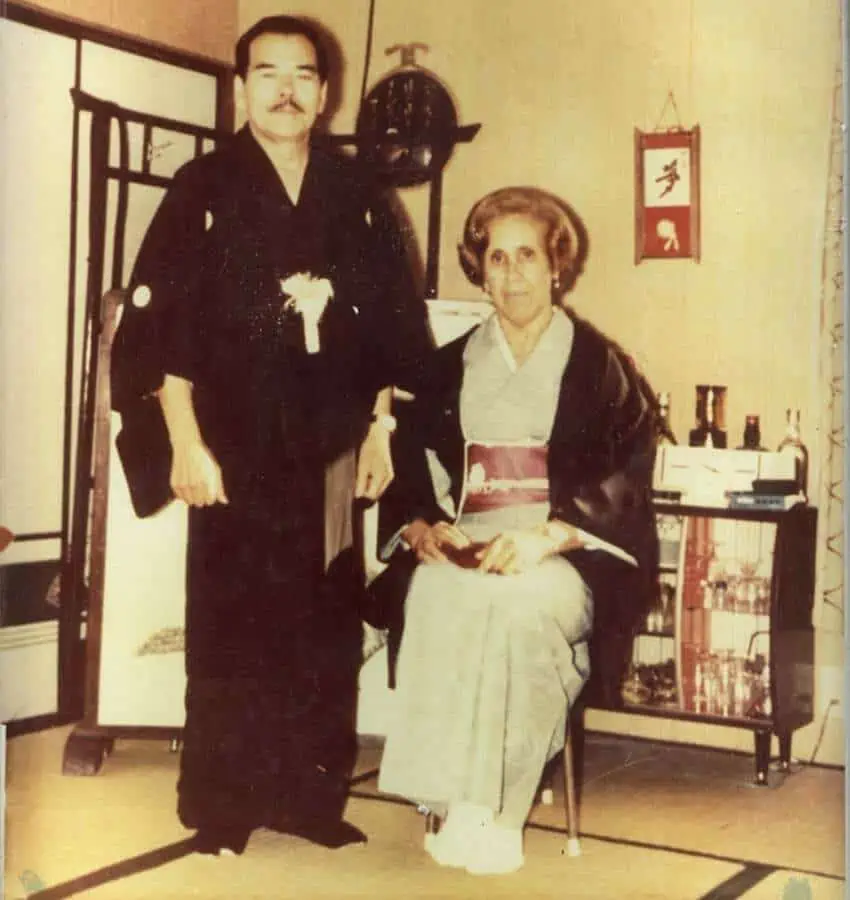

Nakatani liked to sing and would go up to the roof to do so. The landlady’s daughter, Ema Ávila Espinoza, found him up there when she went to do the laundry, and she began to teach him Spanish words.

The couple were married and had children within a year. Nakatani would never speak the language well, but he understood it.

The couple continued to grow their family, and Nakatani worked with his Japanese employers until the outbreak of World War II, an event that complicated things for the small Japanese population in Mexico. Many returned to Japan voluntarily, and others, like the lead supervisor for El Nuevo Japón, were accused of spying for imperial Japan, deported and had their businesses shut down, which meant that Nakatani no longer had a job.

Any Japanese people on the coasts and border zones had to move to the interior of Mexico for the duration of the war. Already in Mexico City, Nakatani did not have to leave his Mexican family, but they did have to live in one of the Japanese neighborhoods in the capital for both support and protection.

With Nakatani’s job gone, the young couple needed a way to feed their family. They began by making and selling traditional Mexican snacks from their home. But what changed their lives was the decision to adapt a Japanese snack food to Mexican ingredients and tastes.

In his rural hometown of Sumotoshi, Nakatani learned to make orinda: mamekichi seeds with a sweet, rice flour-based coating. Having neither the seeds nor rice flour, he improvised with peanuts, wheat flour, soy and sugar to make a coated fried peanut that is mostly salty with a touch of sweet.

The peanut snack slowly became popular until there were lines of people waiting to buy the “cacahuates del japonés” (the Japanese guy’s peanuts). Eventually, the couple decided to move the business out of the house to a stall in La Merced, the city’s main traditional food market.

Soon afterward, they began to sell the peanuts wholesale, inventing machinery to keep up with the demand. La Merced remained their sales base, and by the 1950s, they had a factory set up in the southeast of Mexico City.

The children had been involved with the business almost since the beginning. It became more formalized in 1950 with the help of their son Armando under the brand name Nipón. That same year, daughter Elvia drew the geisha that still appears on the package.

Into the 1970s, the business continued to grow, incorporating in 1975. In 1977, the brand was officially registered.

What they never did, however, was patent the idea. Imitation brands such as Nishikawa were on the market by 1957, a brand that still exists and makes its peanuts in Mexico City.

By the 1980s, the market for the peanuts grew large enough that snack food corporations Barcel and Sabritas took notice and created their own versions. Nipón found it difficult to compete in price with the giants but managed to continue in part by exporting to Brazil, where the snack is also popular.

The Nipón company remained independent until it was bought out by the Totis brand in 2017, which still sells the peanuts under the Nipón name.

Many sources that discuss Nakatani’s peanuts talk about a similar snack sold and eaten in Japan, where they are supposedly called “Mexican peanuts.” It is true that there is a coated peanut snack called takorina that has the image of a stereotypical Mexican guy on the package, but the notion that it is a Japanese version of the Mexican snack food may be an internet myth.

According to the media outlet Vice, takorina peanuts were invented in Okinawa, a place with a different cuisine from the rest of Japan and known for adapting foreign foods. Supposedly, the peanuts’ flavor is based on a dish there called “taco rice” — which takorina sounds vaguely like — and is spicy and savory.

Marrying into a Mexican family helped Nakatani to integrate and gain acceptance. He lived in Mexico City until his death in 1992 but never became a Mexican citizen. According to a daughter-in-law, he still felt loyalty to his home country.

His first son, Carlos, born in 1932, became a painter, sculptor, cinematographer and writer. Another son, Yoshio, became a noted singer.

However, the family will always be best known for its peanuts.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.