Day of the Dead is more than just welcoming back our loved ones to “eat” tamales. Images of Frida Kahlo, heroes from the Mexican Revolution, and even local personages appear on public altars, not because anyone might be related to them, but because these people are important to cultural identity.

While we might not think of ourselves as such, we foreigners living and exploring Mexico are part of an inter-generational phenomenon, which has a long history and even unsung heroes.

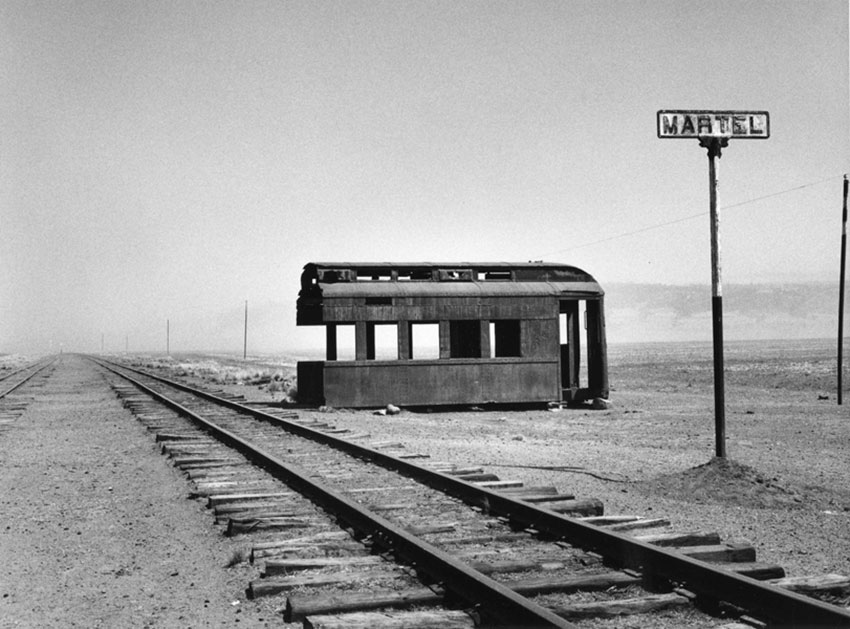

One of these heroes is U.S.-born photographer Mariana Yampolsky, perhaps the most important documenter of folkloric Mexico of the mid and latter 20th century.

Born in Chicago in 1925, she was a first-generation American whose family had strong political views. After graduating from college in 1944, she came to Mexico to study painting and participate in the country’s strong socialist and anti-fascist movements. She was one of the first foreigners to be fully accepted into the militaristic Taller de Gráfica Popular artist workshop, which was and is best known for its graphic work.

Their influence shifted her focus to graphic art, but more importantly, she decided to document the Taller’s work through photography.

The generation of Mexican artists she worked under included greats such as Leopoldo Méndez, Pablo O’Higgins, and Alberto Beltrán. She also studied with renowned artists Lola and Manuel Alvárez Bravo, two of the photographers that had set the standard for photographing the country in the 20th century. These experiences helped her to “fall in love” with the rural Mexico of that time, its people, folk art, landscapes, politics, and culture.

This love for Mexico included extended travel in the country, although that was far more difficult than today. She began traveling the country long before the modern toll roads and the hotels in every town of any size, not to mention widespread internet or even landline phone service.

Longtime friend and fellow artist Helen Bickham traveled with her on various occasions. Her stories include sleeping on dirt floors in small huts and even an incident where the two had to negotiate ferry passage between two rival towns in Veracruz.

Despite appalling or non-existent roads, people who had rarely or never seen a güera (light-skinned woman) before, she traveled over much of the country in her little Volkswagen Beetle and sometimes even on burros.

She did some of her travels for commissioned work, but very often it was simply to see and photograph the country she adopted. Over her lifetime, she took over 66,000 photographs in Mexico, a tremendous number if you consider the expense and difficulty of analog photography, especially in the past.

Her themes are those considered “classic” for Mexico: native plants, farm workers, traditional rituals, and those related to poverty. Those that veered away from these topics, such as architecture, were specifically because of commissions. Some of her best known work includes The Blessing of the Corn (1960s) and Apron (1988).

One of her concerns was that a rapidly modernizing Mexico would lead to the loss of its uniqueness and its people’s sense of community.

Yampolsky’s talent and determination allowed her to make the transition from amateur to professional photographer by 1949, working for publishing houses and government entities.

Her work still appears in Mexican books, newspapers, and magazines because of their importance.

Her first exhibition as a photographer came in 1960. Over her career, she contributed photographs and graphic work for 17 books, with 50 individual exhibitions and 150 collective shows to her credit. Her work is documented in over a dozen books dedicated solely to her, and her work is part of public and private collections around the world.

Yampolsky is one of those foreigners who chose to “go native.” Mexican writer and close friend Elena Poniatowska is widely quoted as saying “Mariana was born in the United States but she got sick of being thought of as a gringo because she loved Mexico in the way that only converts generally love God.” Yampolsky became a Mexican citizen in 1958, renouncing her U.S. citizenship.

Yampolsky, who died in 2002, wanted her photograph and negative collection to stay in Mexico, so the Mariana Yampolsky Foundation was founded and functioned until 2018, when the collection was turned over to the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City for safekeeping.

Unfortunately, this means that it can be very difficult for the average person today to see her work, but it is possible to see some of it online such as this collection on Pinterest.

This is a shame because her work strikes a chord in the U.S. psyche as well as the Mexican one. Part of it indeed is that the imagery is now so classic for depicting Mexico, but there is something else.

Yampolsky, like expats before and since, fell in love with the Mexico of her time, and was concerned about it disappearing, being destroyed by the never ending march of change.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 17 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture. She publishes a blog called Creative Hands of Mexico and her first book, Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta, was published last year. Her culture blog appears weekly on Mexico News Daily.