The Monte Albán ruins sit majestically on a flattened hilltop in the Valley of Oaxaca, about 9 kilometers (5.5 miles) west of the city of Oaxaca. The site on which it stands has been occupied for over 1,500 years by various groups; first Olmecs and then the Zapotecs and Mixtecs.

The Zapotecs built the city, which for over 1,000 years was one of the most important in all of Mesoamerica. But despite its importance, no one today knows what its Zapotecan name was.

Several possibilities have been put forward, including Colina de Jaguar (Jaguar Hill), Montaña Sagrada (Sacred Hill) or Cerro del Tigre (Tiger Hill). And it’s not clear where the name Monte Albán came from either.

It may have been the name of a Spanish soldier, or it may refer to the Alban Hills in Italy, although why it would be named for some Italian hills is a mystery. It’s also thought that Monte Albán may be a corruption of the original Zapotecan name.

Olmecs were the first to occupy the site and may have carved some of the stones known as Los Danzantes (The Dancers). At the very least, that civilization influenced their depictions, since some of the faces have distinctive Olmec traits, such as large heads and thick lips (more about these intriguing stones later).

It’s generally agreed that the Zapotecs arrived around 500 B.C. At that time, another Zapotec city now known as San José Mogote was the largest city in the valley. It’s believed that rulers from there decided to build a new capital on top of a hill primarily for defensive reasons — the period was characterized by ongoing warfare, and locating a city on top of a hill would certainly provide more security.

At its start, the city covered about 800 acres and had an initial population of about 5,000.

Between 500 and 150 B.C., the city grew to cover 1,092 acres, and its population expanded to about 17,000. This explosive growth is believed to be due to the relocation of residents from San José Mogote which, along with other sites in the valley, showed a rapid decline in population.

The city’s population continued to grow, reaching its peak of 35,000 between A.D. 250 and 500. It appears that the city’s center was reserved for the ruling elites while the bulk of the population lived outside the center, where they grew crops on terraces.

The city began a slow decline around A.D. 500. Then, for reasons still unknown, it collapsed completely between A.D. 850 and 900. It was then occupied sporadically by other groups, most notably Mixtecs.

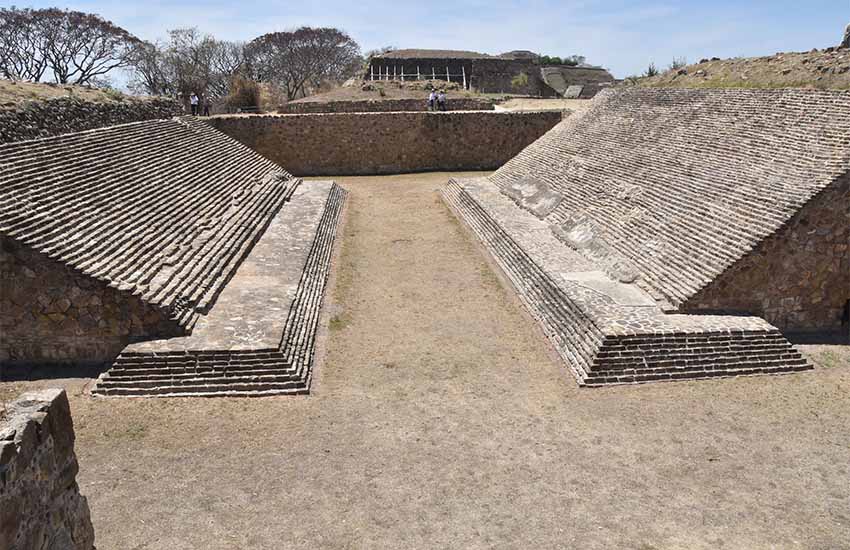

Monte Alban’s spectacular Main Plaza, which measures 300 by 200 meters, has pyramids, a palace, an observatory, at least 170 tombs and large slabs covered with hieroglyphics. Along its periphery are buildings believed to have been temples and which also housed the ruling elites and priests. There are two well-preserved ballcourts on which a game called tlachtli was played. Its architecture, ceramics and murals show the influence of Teotihuacán, a major urban center located about 500 miles directly north in what is now the state of México.

One of the most interesting buildings is the boringly-named Building J, which was constructed around 100 B.C. It’s shaped like an arrow, something unique in Monte Albán, and most archeologists believe it was an observatory. In addition, the site was also where Monte Albán’s rulers announced their victories over neighboring groups.

Along its sides are more than 40 carved stones with the names of different places. Many also have upside-down heads and additional writing. It’s believed that the names refer to areas conquered by Monte Albán. The upside-down heads may represent sacrificed captives.

The carved stones known as Los Danzantes are located outside Building L. Over 300 of them depict naked men, some with their genitals appearing to be mutilated. Carved between 350 and 200 B.C., they are called The Dancers because their convoluted shapes led researchers to believe that the figures depict dancers. That theory, however, has been rejected.

Although it’s now generally believed that they depict tortured and sacrificed war captives, some of whom are identified by name, a 2019 paper offers a radically different explanation: instead of sacrificed captives, it argues that the carvings depict the city’s elites in positions mimicking those of jaguars. If so, this would suggest that the stones were carved not by the Olmecs but by the Zapotecs.

In Zapotecan culture, the jaguar represented the land and fecundity, and its roar was believed to be the voice of the mountains. In Monte Albán, the jaguar was revered as the city’s guardian god. Researcher Fahmel Beyer also argues that the figures don’t display genital mutilation. Rather, he believes that the area’s covered with a flower glyph, which represents a sex organ.

Monte Albán was named a World Heritage site by UNESCO in 1987. Currently, a little over 5,100 acres of it are protected land. An agreement between Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) and the municipality of Oaxaca city in 1993 gives INAH the power to control any proposed development in and around the site and allows for archeological investigations.

The fastest way to get to Monte Albán is by car or taxi. A taxi will run 140 to 180 pesos (US $7 or $8). There are also buses that cost about 8 pesos, but the trip takes much longer and the buses tend to be packed. The entrance fee is a modest 85 pesos.

The site is open every day from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Like many ruins across Mexico, there’s precious little shade, so sunscreen and a good sun hat are must-haves. And water. Once past the entrance, there’s none to be had.

Figure about two hours to leisurely explore the ruins. The museum is currently closed, but you can grab a drink and a snack in the restaurant and pick up some souvenirs in the gift shop.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.