Its enormous crystals were up to 14 meters long and two meters thick, located inside a cave so hostile that no one could stand to be inside it for more than a few minutes: the whole world was stunned when the first pictures of the Naica Crystal Cave went viral.

As we celebrate the 20th anniversary of the cave’s discovery, it still leaves us gasping in astonishment.

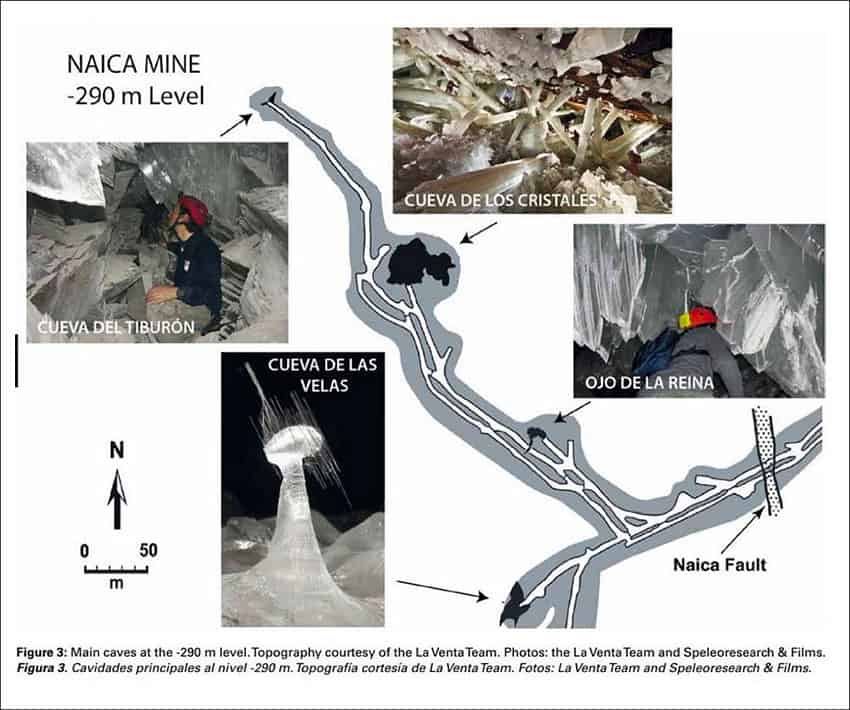

This incredible cave is one of very few places that could be called — in the same breath — “the most beautiful place on earth” and “one step away from Hell.” It was only ever accessible from a tunnel in the Naica Mine, the largest lead, zinc and silver mine in Mexico, operated in Chihuahua by Industrias Peñoles, but today both that tunnel and the cave are entirely under water. But that may actually be to the natural phenomenon’s benefit.

Recently, I caught up with speleologist and historian Carlos Lazcano, the first scientist ever to set foot in the Naica Crystal Cave. Here is his recollection of that experience:

“Twenty years ago, several of my fellow students of geology happened to be working in mines in Chihuahua, and one day I went over there to hang out with them a bit. This is how I bumped into the foreman of the Naica mine.

“As we were chatting, he mentioned that they had dug a new side tunnel with the idea of installing an air-conditioning unit there for the deepest levels of the system. In the process, he said, they had broken into a new cave: would I like to take a look at it?

“I told him I certainly would, and as soon as possible because I knew that the previous caves they had found in Naica contained large crystals. The most famous was La Cueva de las Espadas, the Cave of Swords, which had been discovered in 1910. Although the cave had been systematically trashed for 100 years, it still boasted crystals up to four meters in length, and it was so fascinating that I was really curious how it must have looked the first time they entered it.

Lazcano found his answer when he stepped into La Cueva de los Cristales.

“It was a surprise with capital letters! I was amazed not only at the size of the crystals but also at the aggressiveness of the environment surrounding them. The temperature was 50 degrees Centigrade (122 F) with 100% humidity.”

By chance, Lazcano got a visit from Claude Chabert, one of France’s most famous cavers.

“In April or May of 2000, we got full authorization to explore the cave, so the two of us were the first speleologists to try to study it. Both of us were excited by those bizarre giant crystals, but at the same time, we just couldn’t believe how hostile the cave was. We couldn’t stay in it for more than five minutes at a go! If we tried to make it to six minutes, we felt like we were dying!”

That’s when it occurred to him to contact his friends at Italy’s La Venta Association, which organizes scientific underground expeditions. He knew that they had explored volcanic caves there where the temperature was around 80 degrees Celsius (176 F), so he wrote to them and sent them pictures.

“I couldn’t believe how fast they showed up here … and that’s how Project Naica got started!”

The Naica Project, which consisted of 12 working trips to explore the cave and study everything in it, was organized by La Venta Exploring Team, which got its name from a 1990 speleo-archaeological project along Rio La Venta in Chiapas. Here, the team discovered and studied dozens of caves, most of them used by the Zoque Indians as long ago as B.C. 300. Since then, La Venta has carried out projects from Myanmar to Patagonia.

I have the privilege of knowing some of the scientists who participated in the Naica Project and asked them for their comments on working in this cave. One of those scientists is Professor Paolo Forti of the University of Bologna. Forti is coauthor of the book Cave Minerals of the World and past president of the International Union of Speleology. He is also one of the funniest men I’ve ever met and had us all in stitches when he showed up on an expedition to Saudi Arabia’s desert caves wearing a business suit.

“Don’ta worry,” he told us in his uniquely Fortian English. “In one minute I now transform myself into a real caver!” And from his pocket he pulled a most amazing paper boilersuit made of indestructible Tyvek.

“What was it like working in that cave?” I asked Forti.

“Never in the wildest dreams of my youth,” he said, “did I imagine seeing crystals such as these, così belli, così perfetti (so beautiful, so perfect). In theory, perfection doesn’t exist in this world, but the closest things to perfection on our planet are the crystals of Naica. So I must say that the Naica ‘adventure’ was probably the most exciting and scientifically productive activity of all my speleological life.”

The other Naica researcher I know is Dr. Penelope “Penny” Boston, famed among cave scientists for her studies of Cueva de la Villa Luz in Tabasco, which is the home of “snottites,” stalactite-shaped living colonies of bacteria which produce concentrated sulfuric acid.

Today she works with NASA and is a leader in designing techniques for the exploration of lava tubes on Mars.

“How did you find the Crystal Cave?” I asked her.

“Hahaha … hot!” she replied. “It was like being in a sauna for a long time while climbing around with difficult footing and trying to do delicate scientific operations all at the same time. It was extremely challenging.”

I knew she went into Naica looking for signs of life hidden inside the crystals. “Did you find something?” I asked her.

“Yes,” replied Boston. “We grew a number of interesting microbial cultures taken from fluid in the inclusions we extracted from the giant crystals. We also studied organisms that we took from the amazing red material on the walls. That material appears to be clay and iron oxides ‘glued’ together by a mesh of microbial filaments.”

In 2017, Boston announced that the cultures she and her colleagues had grown from the dormant microbes inside the crystals were genetically distinct from anything known on Earth. She also suggested that those microbes must have been trapped inside the crystals for somewhere between 10,000 and 50,000 years.

When I asked her if she had any other comments about her

extraordinary experience, Boston’s eyes went dreamy.

“The beauty of the environment was completely entrancing. It was a precious gift to be able to experience that amazing place and to help promote the scientific understanding of how this system came to exist and [of] the wonderful micro-organisms that are living in this extreme environment,” she said. “The first time I entered … tears came to my eyes and I put my arms around some of the giant crystals and felt that I was actually a part of the cave system. That day, when I got out, I wrote a poem about it.”

At the height of Project La Venta — Mexican cinematographer Gonzalo Infante decided to make a documentary inside Naica in order to allow the world to see what could surely be called “The Eighth Wonder.”

Every video camera tested by Infante failed, and they finally resorted to using a robot-mounted Nikon still camera to literally shoot the movie one frame at a time. “To get 10 seconds of movie, the robot had to shoot stills for six hours,” said Infante. “Many times, we just left the thing on, and it would run all night long.”

The results of Infante’s efforts can be seen in a National Geographic clip using his footage.

A few years ago, the Naica miners broke into an aquifer. Try as they might, they were unable to stop the flow of water. As a result, that part of the mine —and the cave — are now flooded.

But nothing could be better for those giant cave formations, which were already beginning to deteriorate once they were immersed in air instead of water. Today they are protected and who knows — someday in the future, mankind may again gaze, for a few brief moments, upon the world’s largest natural crystals.

To commemorate the 20th anniversary of Naica’s discovery by the scientific community, Naica the Crystal Caves, a 255-page English-language coffee table book with spectacular photos, will be published this year by La Venta Association.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.