“Let’s go camp on top of Ceboruco Volcano to see the Lyrid meteor shower,” suggested my friend, geologist Chris Lloyd. “The next morning, we can go take a look at a fumarole with beautiful sulfur crystals. It’s in the upper crater.”

Now, a fumarole is a hole that emits hot gases and vapors, and Ceboruco is a big volcano in the state of Nayarit, a two-hour drive northwest of Guadalajara.

Ceboruco was one of the first places I described in my Outdoors in Western Mexico books. I had been lured there by the man guarding the archaeological ruins outside the nearby town of Ixtlan, Nayarít.

“If you’re looking for a place to camp around here,” he told me, “all I can say is that the most beautiful sight I have ever seen is the view from the top of Ceboruco volcano.”

Like him, I too had been enchanted by the massive mountain and its most impressive crater and had returned countless times to camp and hike there.

For this reason, I found it a bit embarrassing to ask Chris my next question: “The upper crater? You mean Ceboruco has more than one crater?”

“Oh, John, you have no idea. There are nested craters on Ceboruco: at least seven! You have to go see this for yourself.”

Once again, I was hooked.

We left for Nayarit late in the afternoon of April 22, the day numerous internet sites said we had the best chance to see shooting stars — “perhaps 100 per hour,” some sources claimed.

We exited the Puerto Vallarta toll road, crossed the little town of Jala and started up the steep, well-maintained road to the antennas at the top of the volcano.

“This time of day, we’ve always spotted roadrunners,” I told Chris.” I guarantee we will see one.”

And we saw two — which is two more than the number of shooting stars I saw not many hours later when we were lying flat on our backs near our tents gazing up at a perfectly clear sky unaffected by the glow of any nearby cities.

At 10 p.m., I gave up and crawled into my tent. Chris persevered and finally saw two. The following day, I saw enough craters to make me forget the Lyrids completely.

We started along the trail that I traditionally followed to reach the only crater I knew. This takes you past picturesque green meadows overshadowed by great, high walls of jet-black lava rubble, a stunning contrast that never fails to astonish me.

“Why are these walls so nicely vertical?” I asked Chris. “Did the lava come up against some obstacle that is now gone?”

“You see a wall because this lava wasn’t flowing horizontally. It was actually pushed up from below through a fissure which we call a dike — and it solidified right there, cracking and crumbling as it cooled.”

After a walk of two kilometers along a well-worn path sign-posted “Crater,” we turned onto a side trail heading steeply upward (at N21.13176 W104.51429, if you have a GPS).

This trail takes you right up the spine of a great, narrow, curving wall. From the top of the ridge, even non-geologists could see that they are standing on the rim of a very big crater — definitely not the crater I’ve been visiting for years.

This I will call the High Crater, to distinguish it from the others.

The view was utterly magnificent. Eventually, you reach a point where you see the High Crater simply by turning your head to the left and the old “Traditional Crater” far, far below, when you look to the right.

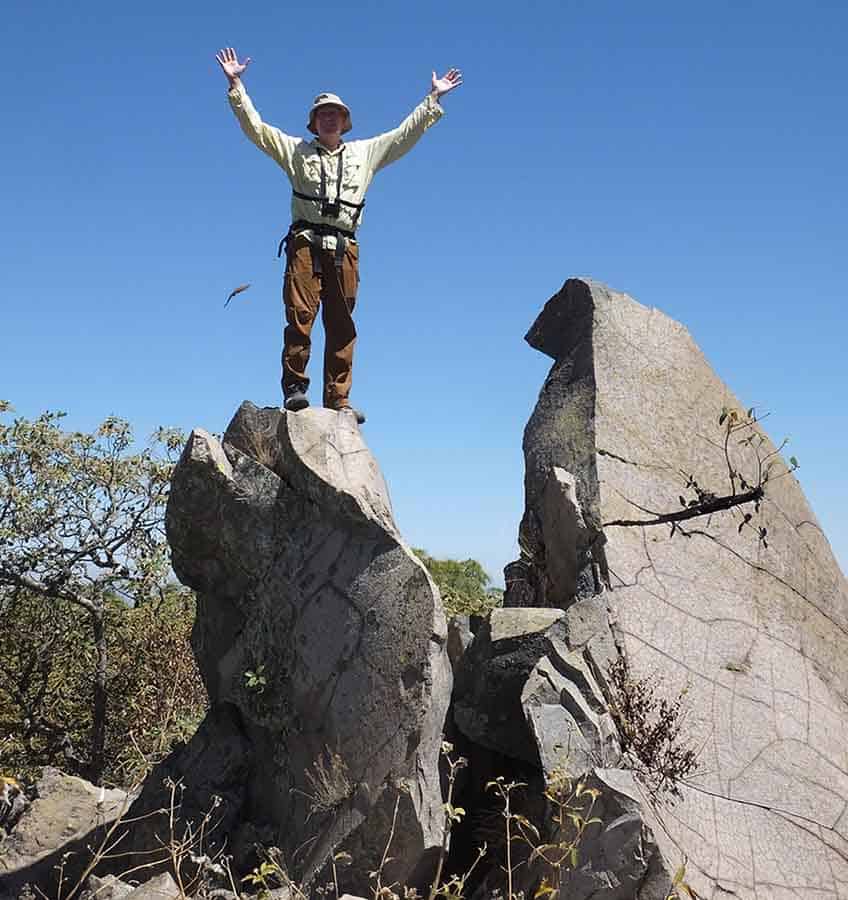

Once we rounded the High Crater and reached the opposite wall, we found ourselves standing at the very pinnacle of Ceboruco, my GPS indicating an altitude of 2,281 meters.

From this point, looking southeast, what did I see but yet another crater, so huge that I had never recognized it as such even though I had driven right through it on the way up.

This one I’ll call the Puma Crater In honor of the nocturnal visitor I had while camping there a year or so ago.

From the very highest point on Ceboruco, we descended into the High Crater to visit several fumaroles and, of course, to gaze in awe at the enchanting yellow-green, featherlike sulfur crystals.

Finally, we completed our loop of the High Crater and returned to the main trail. I asked Chris for a geological resume of how Ceboruco volcano was formed — in layman’s terms, naturally.

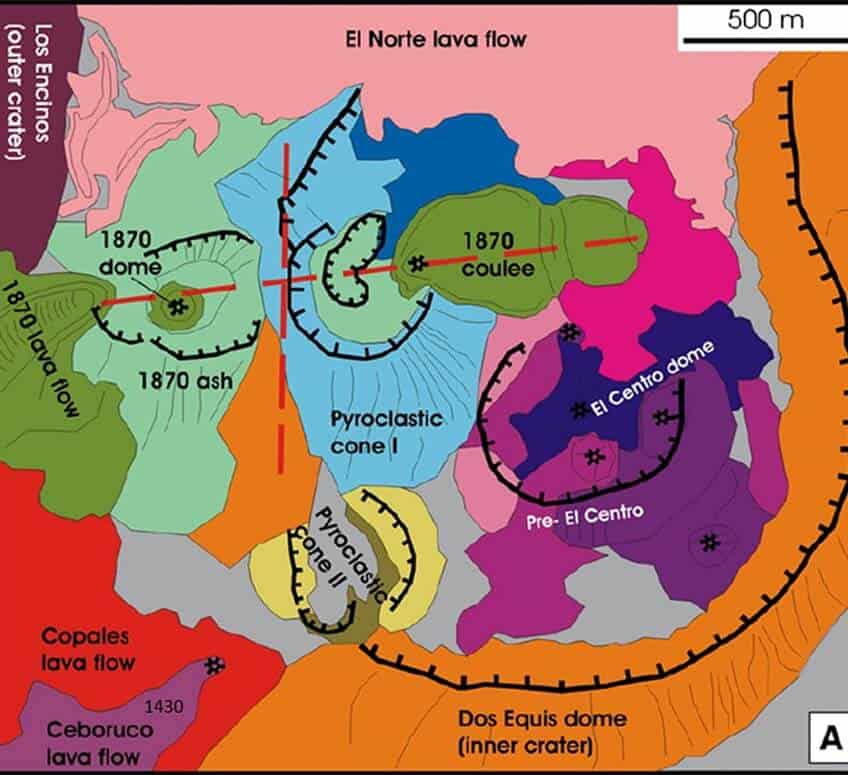

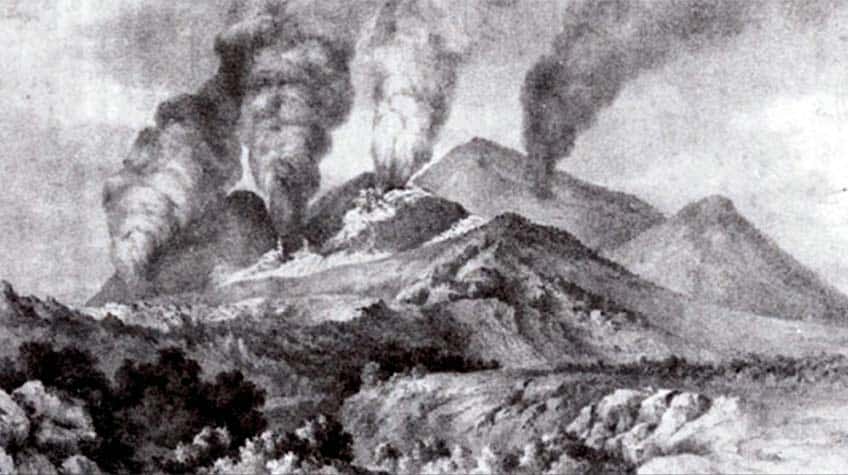

“Volcanic activity around here started in the year A.D. 1000,” began my friend, “but Ceboruco’s big explosion took place in 1005. Around 3.5 cubic kilometers of material were ejected into the air. This was a very volatile pyroclastic event three times the size of the Mount Saint Helens explosion.”

I learned that the column of ash rose as high as 30 kilometers and only recently have researchers discovered proof that tephra particles from what is now called The Great Jala Plinian Eruption of Ceboruco reached as far as Europe.

After that, things were quiet for one hundred years, Chris told me, and then, in 1100, there was another big explosion which sent two cubic kilometers of volcanic rubble and ash (called jal in Mexico) into the air.

Curiously, more events took place in 1200, 1300 and 1400, nicely spaced one century apart… and then there was a long period of quiet until 1870.

Commented Chris: “This is when the Dos Equis Eruption, as they call it, occurred. It was the volcano’s last gasp, and you can see it today at the very top of Ceboruco, just above those fumaroles with the sulfur crystals.”

“Last gasp,” by the way, is a very relative expression. Ceboruco is, today, considered among the five volcanoes with the highest risk in Mexico, and the second most active in the western Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt after the Colima Fire Volcano.

Although Ceboruco gets relatively few visitors — and the upper area, hardly any at all — there is a very well delineated trail all along the narrow rim of the highest crater. My suspicion is that this trail was blazed long ago by explorers who, like some of us today, were curious to see all of Ceboruco from its highest point and felt a sense of awe upon discovering its many nested craters.

Ceboruco Volcano is about two hours from Guadalajara and three hours from Lake Chapala. An ordinary car can make it, but a high-clearance vehicle would be better.

You’ll find the hiking trail to the High Crater on Wikiloc.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.