A 4 1/2-century-old “child” called the Niñopa is the most important religious icon in Mexico City’s borough of Xochimilco and the star of an upcoming celebration.

Despite its age and the pandemic, this image of the infant Jesus continues its important role in this formerly agricultural area. At 51 centimeters tall and weighing 600 grams, it looks much like any other baby Jesus that appears in manger scenes all over Mexico. But this statue is the star of Mexico’s last hurrah of the Christmas season – Candlemas on February 2, marking the presentation of the infant Jesus to the temple — these days done at a church.

This representation is indeed special, even with its own name — the Niñopa (or Niñopan). The niño part is from the Spanish word for “child,” but the “pa/pan” part is in dispute. It may be a shortening of padre (father) or patrón (patron), or it could be from the Náhuatl word for “place.”

What is known is that this image and the popular rites associated with it have a long history.

The Niñopa was created in 1573. Although legend says it was brought from Spain and made of orange tree wood, it was created in Xochimilco from a local tree, most likely by an indigenous artisan. There are several stories about how and why the image has its highly venerated status. One says that it belonged to the last indigenous ruler of Xochimilco, Martín Cortés de Alvarado.

The historical context indicates that it was part of an effort by evangelists to substitute Catholic imagery into indigenous rituals. It is known that Huitzilopochtli, the god of war, was worshipped here in the form of a child. So it would not be too difficult to substitute one “child” with another. In fact, one of the persistent tales told about this image is that it hides a figure of Huitzilopochtli inside.

Like other famous religious images and statues, the Niñopa has been credited with miracles. These tend to be related to health, domestic peace and economic help. Almost all claims of miracles are local, but some have come from as far away as the United States, supposedly just from seeing the statue’s image on television.

In many ways, this image is thought of as a real child. Many believe that it comes alive at night, playing with donated toys and even wandering around outside. People state that in the morning they find the Niñopa’s belongings strewn about the room in which it sleeps, small footprints in the earth outside or its dirty clothes.

The Niñopa is indeed cared for as if it were a living child. It does not reside in the parish church; instead, each year, a family becomes the child’s “nanny” for 365 days.

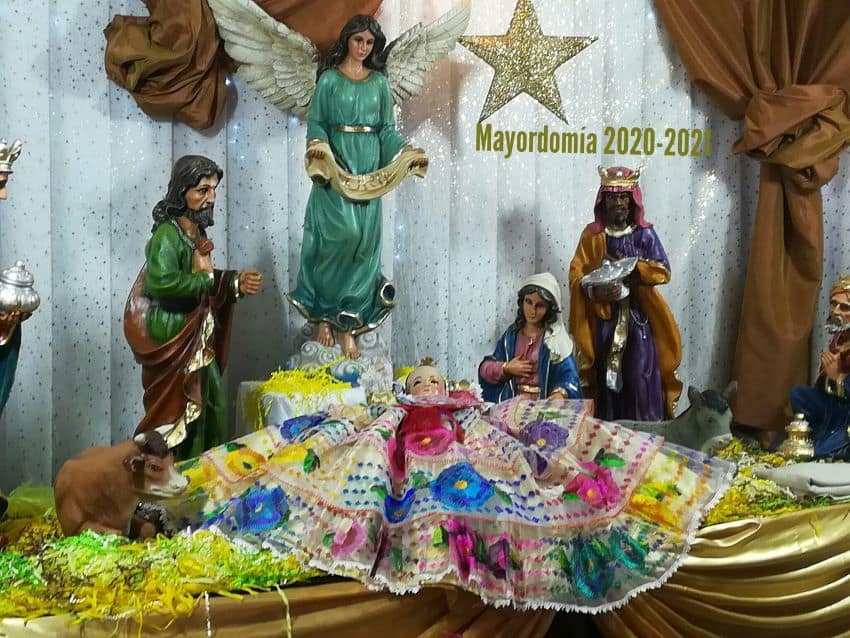

The child is “laid down to sleep” each night and “woken” each morning with music before being dressed for the day. Care of the Niñopa, as well as ensuring that it does its official duties — such as attending Mass — is the responsibility of the family hosting him, who are called mayordomos.

Becoming a mayordomo is a serious and expensive undertaking. Chosen families prepare for years, even decades, for the honor of spending a year as the official caretaker of the statue. A room is dedicated to the child, often added to the house. In normal years, this room needs to be accessible so that the public can easily visit, and the image is taken out daily to visit the sick, go to Mass, and appear at festivals. Even routine outings are done with great fanfare, with the mayordomos footing the bill for dancers, food for everyone and more.

Important festivals related to the Niñopa are Children’s Day (April 30), the posadas before Christmas (December 16–24) and Kings’ Day (January 6). But by far the most important event is Candlemas, when the image moves onto a new family and home. The festival is important enough that it is covered every year by Mexico City media.

Concerns about preserving the condition of the centuries-old statue have led to some changes in how it is handled and how it performs its duties. Clothing cannot have zippers or other metal. Worshippers cannot touch the image directly, only its clothes. It has been on “sabbatical” on several occasions for restoration work by the National Institute of Anthropology and History — locally called “going for a check-up with the doctor.”

The year 2020 has not been normal for anyone, the Niñopa included. As you can imagine, the pandemic has all but shut down festivities related to the image, and visits at the mayordomo’s home are not permitted either. When the transition to the new mayordomo household occurs on February 2, few people will be authorized to attend the ceremonies in person.

However, the current mayordomos, the Paredes Valverde family, says the transfer will be shown live online. This promises to be a positive long-term development, maybe a precedent that will make the child even more accessible to more believers and those of us who are fans of Mexican culture.

There are several Facebook pages dedicated to the Niñopa, but the official is updated regularly with new photos and videos, and believers leave heartfelt messages in the comments section.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 17 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture. She publishes a blog called Creative Hands of Mexico and her first book, Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta, was published last year. Her culture blog appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.