Drumming is heard in the distance like a war cry. It is a pounding, trancing rhythm set amidst an otherwise quiet scene.

A few gusts of wind blow sand swirls around a large, somewhat empty courtyard. This area soon fills with vivid colors — women and young girls in elaborate ruffled patterned dresses. The drumming intensifies.

The courtyard soon reveals the drummers, men and boys moving in swift procession. The leaders at the front don bandanas around their heads and a bow and arrow adorned with raccoon skins. Behind them are young men in hoodies and sunglasses with kerchiefs around their faces.

Some of them hold intricately painted swords. Their expressions are stoic and focused. The procession stops just outside the church as groups of the vibrantly dressed women gather swiftly inside a striking church, a misión filled with intricately designed murals.

Prayers are said, and then as quickly as they entered, the group filters out of the church. The drumming picks up pace, and intensity once more, as the procession of both men and women flows out into the village again, this time with wooden statues of Jesus and Mary thrown over the shoulders of the pack in front. Jesus is dressed in a flannel shirt with a backward baseball cap, much like many of the town’s millennials.

This is a typical scene during Santa Semana or Easter Holy Week, in Cusárare, located near the rugged Copper Canyon in Chihuahua.

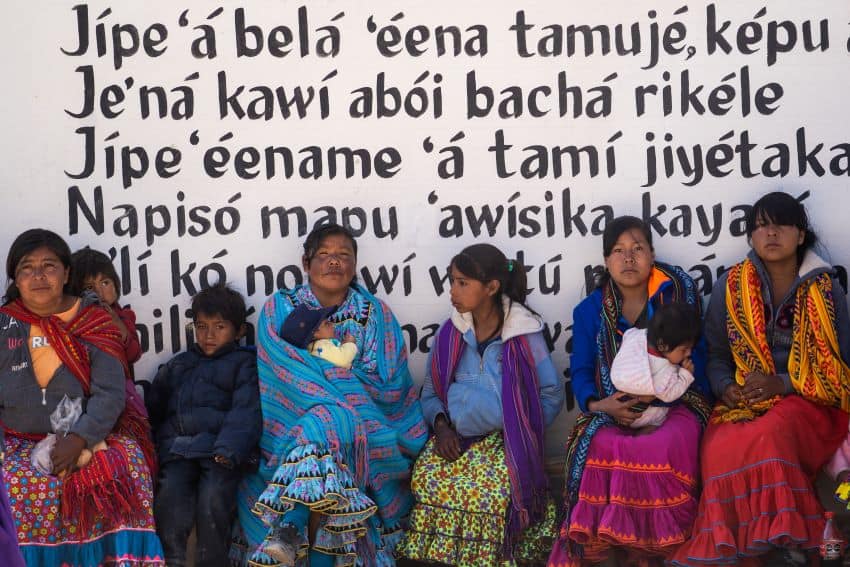

Cusárare is one of many Tarahumara or Rarámuri villages that celebrate the religious holiday period throughout Mexico. The celebrations combine traditional cultural practices, pre-Hispanic traditions and Catholicism.

“It is among the most important festivals for the indigenous people of Chihuahua,” says Jaime Aventura, a Rarámuri reporter for the state government and a tour guide. Holy Week in the mountains of northern Mexico is a spectacle to witness. Outside the famous Copper Canyon is this network of vibrant indigenous communities who celebrate Easter unlike anywhere else.

Rarámuri means “runners on foot.” This group is most famous for being endurance runners, having won ultramarathons wearing nothing but sandals made out of tires. They are also known for maintaining their traditions, identity and customs. The group is insular with some members still living isolated in caves in the northern mountains.

According to local anthropologist Guillermo Ortiz, “their population is approximately 75,000 in the mountains. It is over 100,000, including those who have moved out to cities.”

In recent years, an increasing number of the population has moved to urban areas like Creel for employment due to climate change’s impacts on their farming capabilities or due to violent drug trafficking. Working for cartels has sometimes been necessary for survival.

During Holy Week, the Tarahumara will dance from dawn to dusk to the rhythm of the drum, which they will play exhaustively without rest. The dances signify a clash between good and evil.

With each footstep, they believe they are weakening the Devil and thanking God. There are references to Christ’s death, crucifixion and resurrection. Here, Judas is burned.

Santa Semana is a time for the group to be close to God.

Distance plays a role in how the traditions are maintained.

“Each community’s customs have changed depending on how remote they are,” says Aventura. “Places further away from mestizo areas keep more of the old traditions alive, versus communities near population centers that fall under greater influence from the mainstream Catholic church.”

Some of the more remote mountain villages closed their doors completely this year to outside visitors because of the pandemic.

Almost 75 km away, a similar but different scene plays out. Various communities around Norogachi travel from deep around the Sierra Madre mountains for a large collective Santa Semana celebration. The men here dress in traditional costumes — a tagora, or a long, white cloth tied at the waist that’s subtly patterned at the edges, revealing only a slight covering of the legs.

The tagora links together with a long ribbon, a kovera they wear around their head.

At the beginning of Easter weekend, the participating males will prepare for the celebrations by marking their skin with speckled white spots. This signifies Earth. In Norogachi, one group begins dancing rhythmically.

This same group kicks off the procession with various village members. As the day progresses, different groups join the march until hundreds of people have filled the town square.

The procession scene is vibrant and full of various characters, the dancers, drummers, flautists and captains with flags. The front of the line includes a village woman who bears a large banner of Jesus, a man wearing a large conical hat resembling a piñata, and various mestizo ladies carrying crosses made from palm branches and statues of Mary and Jesus. The remainder of the village, the women, follow the dancers and drummers in colorful streams.

The procession walks around the town repeatedly with more and more members joining. Some of the men start to gather firewood for large bonfires. The evenings are cold, and the fire is necessary to keep dancing and drumming.

And the dancing is endless. It goes into the night and the days that follow. At nighttime, the dancers look zoned out, but their bodies move relentlessly through the unending beat. They essentially have danced themselves into a trance. Families at home will cook continuously, making hundreds of corn tortillas to ensure the dancers are fed.

Their primary source of strength comes in the form of a cigarette or a can of Tecate beer. According to villagers in Cusárare, “beer gives the participants energy” and “more of a kick to continue dancing.”

Villagers also drink jugs of homemade corn beer called tesgüino.

As sunrise envelops the valley, the dancers retreat for a brief rest. The courtyard is strewn with visiting community groups who are still asleep, empty cans of Tecate and the remaining burning embers of the bonfires from the night before. Outside visitors, mostly media and some domestic tourists, congregate at Hostal de Elba, located in the middle of town.

Later that morning in Cusárare, the same courtyard appears empty at first, but the drumming is intense as ever.

The doors this time to the misión are closed. Similar to the day prior, the courtyard eventually starts to fill with the same vividly dressed women. They gradually shift to a hillside overlooking an expansive acre of farmland as the procession of drummers makes its way into this field.

It’s time for the penultimate event of the Santa Semana celebrations: the lucha, or the ultimate struggle. This is a throwdown — a symbolic display of good versus evil, with evil being pushed out.

In the most traditional celebration, villages would be split into groups — chamucos, representing the righteous, and morocos, the devils.

For 10 minutes, villagers clasp each other’s backsides and wrestle while an excited crowd cheers and overlooks. The scene is chaotic — multiple matches going on, stumbling bodies succumbing to the pressure of weight and limbs and legs being thrown down on the sand.

Dust is thrown up in the air constantly, and the scene becomes progressively blurrier. Some of the matches appear friendly and full of laughs; others settle or create new scores.

Once again, as quickly as the prayers started and ended, so does the fight. The villagers gradually clear out of the fields and stream back outside the church’s main square to engage in vibrant chatter. After days of dancing and processions, there is not a hint of fatigue on anyone’s face.

The men and boys rush back to drumming. They walk around the town for one final spectacle, a testament to their most celebrated religious celebrations, their resilience and their strong ties to their culture.

It is a magnificent end to another spiritual year, and they can finally rest.

Mexico News Daily