Eight years after his death, the legacy of ceramics artisan Jorge Wilmot lives on in the establishment of the Guadalajara metro area as a source for world-class ceramics. His fusion of art, technology and design elements from the past reinvented the working of clay.

Wilmot was born in Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, in 1928. He studied fine art at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City for only a few months in 1948, returning to work in Monterrey, where one job was in a factory making dishes.

In the 1950s, he made the important decision to go to Europe to study ceramics in France, Sweden, and Switzerland. Here he discovered Asian techniques, in particular crackled glaze, that would appear in much of his later work.

Upon returning to Mexico, he had an exhibition in Monterrey in 1958. This led to contacts with cultural authorities in Mexico City, where he discovered the traditional burnished pottery of Tonalá, Jalisco.

What is now a suburb of Guadalajara has had a very long history of fine ceramic and pottery work since before the arrival of the Spanish. Its large clay deposits are among the highest quality in Mexico.

By 1960, Wilmot was setting up shop in Tonalá. His goal was to create a new kind of ceramic, based on the traditional wares, but integrating Asian and modern elements in both technique and design. One of his first steps was to work with the local craftsmen to both learn from them and to work toward conserving centuries-old traditions.

After mastering that, he set about using his international training and experience. One main change he made was to use gas-fired kilns on a large scale.

In 1960, Wilmot met American ceramicist Ken Edwards who had also come to Tonalá to develop new pottery. However, Edwards was interested in doing his own thing, a very heavily Oriental-influenced work, rather than reinvent local traditions.

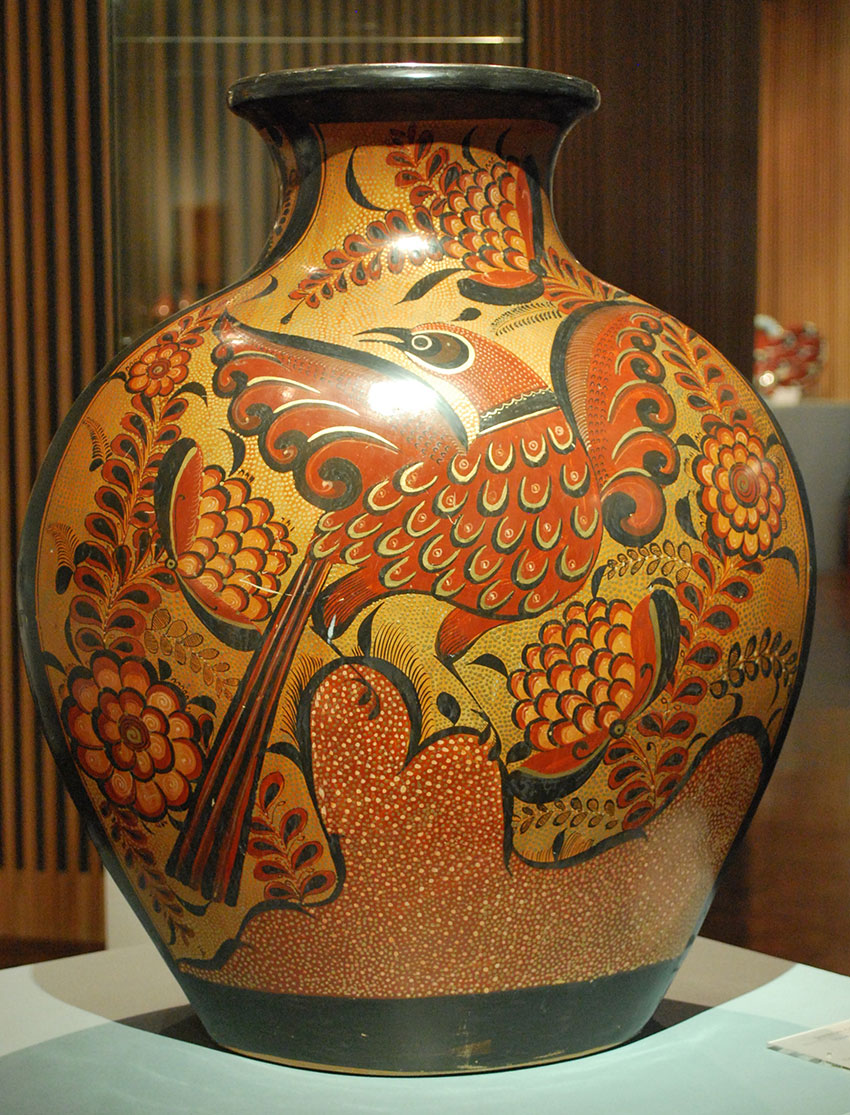

After much trial and error, Wilmot’s workshop developed a distinct inventory. His work had Mexican motifs as a base, but with Asian elements in both technique and design, especially glazes.

It is rather austere compared to native Tonalá pottery, which often attempts to fill in all available space with tiny decorative elements because of its Baroque heritage.

The new work gained acceptance at fine galleries in various cities in Mexico and abroad, especially in Europe, Japan, and the United States. It caught the attention of the head of the minister of culture at the time, Fernando Gamboa, and the business expanded exponentially.

From then until his death in 2012 he would receive various accolades and have exhibitions of his work in some of the world’s most important venues.

Despite his work in reinventing Tonalá ceramics, he continued to be dedicated to preserving the old traditions. In 1986, he established the National Ceramics Museum (Museo Nacional de la Cerámica) in his former house and donated it to the municipality of Tonalá.

The museum still exists with an important collection of work from the pre-Hispanic period to the present.

Perhaps more importantly he established a school that trained generations of ceramicists in the new techniques and designs he introduced, most notably stoneware and other high-fire work. So many craftspeople benefitted from this that almost all of the ceramic that is not strictly traditional shows influence from him. It is one of the main reasons why Jalisco has some of the best artistic production in Mexico.

Workshops that are Wilmot’s “heirs” include Cerámica Netzi in Tonalá and Cerámica (Noé) Suro in Guadalajara. But his influence goes even further. The metro area now has a reputation for fine ceramic in general, attracting designers and master craftsmen to open workshops and design new products. One example of this is the Japanese-inspired work of The Norm in Tlaquepaque.

While Mexican ceramics have a reputation for timelessness, in reality the 20th century was a time of great innovation. Wilmot’s contribution is extremely important because he was able to innovate while maintaining respect for the past.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 17 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture. She publishes a blog called Creative Hands of Mexico and her first book, Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta, was published last year. Her culture blog appears weekly on Mexico News Daily.